Suzanacarlaespindola@gmail.com

Universidade Federal de Pernambuco– UFPE, Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil.

Universidade Federal de Pernambuco– UFPE, Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil.

Universidade Federal de Pernambuco– UFPE, Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil.

Universidade de Pernambuco– UPE, Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil.

Universidade Federal de Pernambuco– UFPE, Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil.

Goal: The goal of this research is to propose a system for the implementation of the standardization of processes, and for their continuous improvement and optimization in the administrative area of companies.

Design / Methodology / Approach: A system for the implementation of process standardization was proposed and carried out through stages for structuring each process.

Results: It was noticed that although no ideal model can be deployed in all organizations, there is a real necessity for companies that need tools to be used and adapted to the needs of each company.

Limitations of the investigation: It is worth mentioning the fact that this work was elaborated considering the specificities of the company and that the planning for the implementation of the necessary changes was performed, observing the particularities of the company.

Practical implications: The study demonstrates that with an organizational restructuring of the company, it is possible to structure internal and external processes, thus creating a faster and more accurate flow of information between departments and allowing lean management by eliminating obsolete and unnecessary processes. Another practical implication observed is the creation, control, and monitoring of indicators to achieve the results of the projected processes, as well as checking of the evaluation of these processes that can be maintained or changed according to the company's strategic planning.

Originality / Value: This article contributes to the strengthening of strategic knowledge aimed at the standardization of administrative processes for the continuous improvement of quality in the services of retail companies and can be applied in companies from emerging countries.

Keywords: Management; Production Management; Program Evaluation; Routing; Scheduling.

According to current requirements, managers feel the need to learn new ways of running their businesses and to foster a team spirit where everyone contributes with their knowledge and experience. Based on this, it is necessary to continuously improve the productive and administrative processes in order to meet this need (Brandao et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018; Perevozova et al., 2019; Purosottama and Ardianto, 2019).

The search for the improvement of production processes and the competition between companies, together with the demands of customers and consumers, has intensified the need for quality improvement (Cesconeto et al., 2014; Watson and Tytula, 1996). This search is the right way to strengthen the company's competitiveness in the medium and long term (Singh and Singh, 2015; Ross, 2016; Ricco and Guerci, 2014). The intermediate activities executed at the organizational level are not directly related to the production of the final product. However, these activities provide the total cycle of an organization: from the raw material purchase to the financial results and balance sheet. Consequently, these activities require a continuous, safe, efficient, and effective process to validate and analyze the information (Silva Júnior et al., 2011).

Modern companies consider standardization as the most important of managerial tool (Cohen and Rozenes, 2017). Great researchers, such as Imai (1986), March and Simon (1958), and Shingo (1981) had this theme as their central concern. They suggested that standardization is an internal and continuous process of an organization. Moreover, Total Quality Management indicates that uniformity is essential for routine management and is a tool for achieving better results. Therefore, standardized processes provide routine management, ensuring greater productivity for an organization, structuring the flow from supplier process to result analysis, and achieving greater efficiency to the needs of each sector. The standardization process provides a visible and measurable improvement of the process, and efficient routine management (Singh and Singh, 2015; Skrynkovskyy et al., 2017). For the overall process to achieve its objectives, it is essential to act on micro-processes, focusing on the primary purpose of an organization.

The standardization and improvement of processes, products and services can be achieved through the participation and commitment of all employees of the organization. The adoption of a management system usually implies the standardization of an organization's methods and practices. This is important to enable critical analysis and the consequent improvement of company procedures and methods, providing a concrete perspective of what to analyze and improve (Wright et al., 2012; Sumarto, 2017; Idzikowska, 2017; Lapchak and Zhang, 2018.)

Regarding confidentiality issues, this article will name the case study ALPHA RETAIL GROUP. The organization did not have business cost assessment management and activity planning and procedures, generating unnecessary expenses, sector deprogramming, demotivation, and loss of productivity. Thus, the objective of this article is to implement the standardization process and routine work management in each department at the organizational level, establishing goals for each activity and applying administrative management tools, in order to achieve excellence in the provided services to internal and external customers. The goal is to propose a practical approach to guide organizations to implement standardization processes. The proposed framework for implementing the standardization process has five steps, as follows:

With the structuring of the company and the indirect standardization of the processes of each department, the Engineering Managers will have a tool for monitoring and analyzing the productivity indexes of each employee, according to established goal for each one. Implementing standardization and defining the ideal model will enable the company to gain greater productivity in its processes, reduce costs and losses and the capacity to evaluate and monitor the performance of its employees.

To bring an organization to excellent results, the manager must have an entrepreneurial spirit, accept challenges, take risks, and have a systematic sense of nonconformity to lead the company to a better situation (Porter, 1979; McMullen and Kier, 2017). The manager is expected to understand the technical side of the business as it relates to product design and manufacture, as well as the business side as it relates to satisfying customer needs profitably (Gorchels, 2003).

The external environment – a macro perspective – and the internal environment – a micro perspective – influence organization performance. The importance of standardization for an organization’s efficient results is becoming stronger nowadays (Singh and Singh, 2015). It is stated in Simon's behavioral theory (1947) that the use of standardized procedures aims to reduce uncertainty.

The degree of absence in the variation of implementation practices defines standardization. According to Singh and Singh (2015), managers need to understand that the standardization process is one of the safest methods to improve productivity and competitiveness at the international level. It is also one of the foundations of modern management. By standardizing the system, organizational improvement is achieved by increasing technical capabilities, knowledge, business profits, and customer satisfaction (Pellicer et al., 2012).

Standardization is a continuous internal process that provides improvements for quality, cost management, compliance, and safe process (Shingo, 1981). It also facilitates the training process for new members, once the procedures and goals to be achieved are identified. Moreover, it provides high process confidence, avoiding organizational dependence on a specific employee. Furthermore, involving employees in the standardization process is vital for identifying the best way to execute a specific activity. Thus, the assessment process is more precise to everyone through the management of indicators (Forno et al., 2016).

Continuous improvement requires employees to constantly revise the current needs and procedures. Imai (1986) studied this concept of continuous improvement and suggested that, if the organization implements the process correctly, it will teach people to utilize methods for eliminating waste in the workplace. Moreover, standardization results from education, training, and delegation, according to an organization's objectives (Chiarini and Vagnoni, 2017)

The whole organization involves processes. Thus, the primary purpose of process design is to ensure that its performance achieves the determined goal (Slack et al., 2010). The Cause and Effect Diagram is a methodology to define and establish a standardized process, which analyzes the necessity of each step of the process to contribute to the primary objective. Defining the goal and the necessities of a process is fundamental for standardization. To map the micro-processes and how each activity is related to one another is very important for designing a procedure. Moreover, it is essential to identify the different types of activities, and the flow of materials, people or information (Slack et al., 2010).

Diverse organizations desire to standardize their processes, but do not know how to do that. Additionally, organizations that are structured by tasks and not by processes need to re-design all their processes, leading organizations to interrupt the implementation of standardization because they are not confident in terms of how to implement it (Chiarini and Vagnoni, 2017). The processes analysis implies identifying different dimensions of processes: flow, the sequence of activities, waits and cycle duration, data and information, people involved, and relationships between the activities. The macro-processes can be subdivided into micro-processes or groups of activities (Forno et al., 2016). Moreover, the standardization process considers technological, personal and structural aspects. There is no defined model, but there are tools that facilitate the structure and implementation of process management through standardization. Process management is common in industrial organization. However, it is not common in the services organizations (Falcão et al., 2017).

Business Process Management (BPM) combines software resources and management knowledge to accelerate the improvement of an organization’s process and facilitate its innovation. BPM also assists in the achievement of strategic objectives and the efficient implementation of processes throughout the organization. Its focus is on top level and bottom line success through vertical integration and optimization work, diverging from traditional management lines such as the functional ones that do not focus on an integration process. BPM also seeks continuous processes improvement, increasing the organization’s competitiveness (Roland, 2009).

BPM is a systematic approach to improve an organization’s business processes which are the set of coordinated activities and tasks performed by people to achieve the organizational goals and objectives. From a process perspective, Business Process Management is regarded as a best practice management principle to help companies sustain a competitive advantage. Process Alignment and People Involvement are two critical concepts for the successful implementation of Business Process Management (Hung, 2011; Hoang et al., 2013; Alotaibi and Liu, 2016). This tool is used in an organization to operate on its internal processes, strategic processes, and people and responsibility management. This methodology focuses on an organization’s processes in order to achieve continuous improvement.

In their studies, March and Simon (1958) treated organizational routines as simple rules for organizing the environment. Within this context, standard procedures would be developed to improve process efficiency and assist decision-making. Organizational routines are increasingly theorized as recursively constituted as structures that inform and influence human action, while simultaneously being built from the bottom up by individual activities (Styhre, 2017).

Regarding routine work, there is a repeated and cyclical section called the activity task. The first step to analyze a routine work is to separate the task into elements and isolate the compatible central part of the auxiliary tasks. It is important to identify common and repeatable tasks since the purpose of this identification is to group the items with the highest repetition frequency and the shortest variation time (Liker and Meier, 2007). Geramian et al. (2017) suggest that the PDCA methodology is the best tool to manage established procedures. The Planning, Do, Check and Action (PDCA) methodology intends to manage repetitive processes, establishing a working standard for each stage, from the initial stage of the project to its final product. This methodology also includes explanations on how to verify inconsistencies, how to identify their causes, and how to correct them.

Although many organizations acknowledge the importance of standardizing processes for efficient process management, most of them consider its implementation burdensome. A process-based restructuring implementation first requires an understanding of the primary organization’s processes. Then, to analyze the current situation, detail the executed process, each stakeholder involved and the required information are identified, and results are expected. According to Harmon (2007), any system emphasizes that everything connects to something. Thus, the routine management is a tool that will allow controlling the processes and the transfer of information from one micro process to another.

Deming (1982) assisted Japanese industries to recover economically from the devastation of World War II. He searched for methods to improve the process itself, resulting in good quality products. Together with Joseph Juran and Armand Feigenbaum, he refined the PDCA cycle. This method is characterized by having a focus on continuous improvement (Silva et al., 2017). In their studies, Gorenflo and Moran (2009) report that the PDCA method consists of four steps, as follows:

According to Silva et al. (2017), an organization requires an operational guideline to manage its activities. Thus, the PDCA method provides a daily work routine management as well as a continuous improvement of the existing processes.

Organizations are always looking for consistent and positive results. The key to that is the development of talent and routine work definition. Therefore, standardization helps employees develop the knowledge and talent they need. According to the Toyota method, standardized work is the foundation for efficient and productive working methods. Defining standardized work requires the ability to evaluate the overall process focusing on training and separate it into the most critical elements (Liker and Meier, 2007).

Defining activity during the standardization process provides an execution guideline. Consequently, it is possible to implement the training process as it is complicated to teach an activity that does not have a defined method of execution (Liker and Meier, 2007). Transforming and improving employee efficiency is the biggest challenge organizations face. Modern processes require strong individual skills to execute them. For a long time, organizations have not acknowledged the value of training their workers as a tool for reducing errors and production costs. Nevertheless, organizations are currently recognizing the training process as resources for such improvement (Alotaibi and Liu, 2016).

Scientific research needs a set of intellectual and technical procedures to acquire scientific knowledge (Gil, 2010). This way, this research can be classified in several ways. As for the research objective, it can be characterized as applied, since the study in question aims to solve problems identified within societies, helping to expand scientific knowledge and proposing new discussions to be investigated (Miguel, 2018).

As for the approach to the problem, the research is qualitative, as Miguel (2008) is the person who researches the partner and starts his statements about pragmatic elements. As for the objective, it is described as descriptive, as it aims to describe the characteristics of a group determined to identify possible relationships (Gil, 2010).

Regarding the method, this research can be classified as bibliographic to verify the gap in the literature (Miguel, 2018). Therefore, the literature review was developed to understand the background of the management process and continuous improvement, focusing on an organizational structure and routine management processes.

The research can also be classified as a case study, which, according to Yin (2017, p. 32), “is an empirical investigation that aims to study a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between the phenomenon and the context are not clearly defined. Thus, this type of research seeks to study in-depth one or more research objects that allow the development of scientific knowledge.

A case study was developed in a retail organization. The group started its activities with only one retail store, with several products, with monthly average revenue of R$ 10,000.00, for more than thirty years. It was a well-structured family with operations in the agricultural environment that saw the opportunity to enter the retail trade. Following the store opening experience, owners have identified an opportunity to represent nationally known brands through franchises.

They closed the first store mentioned and, in 1982, they opened the first store of a well-known franchise across the country, starting activities with the goal of creating a large brand representation group. Today, RETAIL X GROUP represents three reputable and accepted brands in Brazil, reaching a monthly sales average of R$ 4,000,000.00, with approximately 210 employees and 26 stores in total, with plans to open four more stores.

With a very aggressive commercial vision, the group has grown a lot over the last ten years, now needing to structure its rear to meet the demands of its business, with reliability in processes and information. RETAIL X GROUP did not have effective control of its processes, which caused much waste, loss, lack of information and general lack of control. Therefore, it began an investment process in its rear, in technological resources, infrastructure, and people, starting the group standardization project.

Thus, it sought to structure the methodology focuses on both the organizational structure and routine management and follows the activities described below:

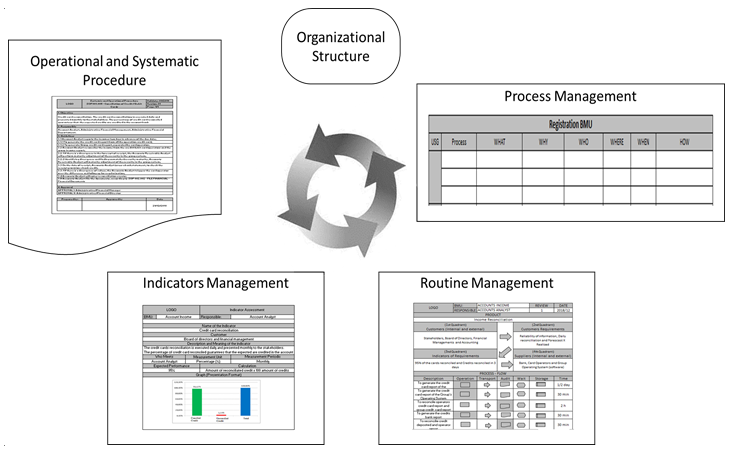

Figure 1 demonstrates the case study methodology. The figure shows the methodology of the case study developed in five pillars: Organizational Structure, Process Management, Routine Management, Indicators Management, and Operational and Systematic Procedure. These pillars will be developed in practice throughout this article.

Figure 1. Case Study Methodology

The ALPHA RETAIL GROUP operates in the retail segment of perfumes, cosmetics, footwear, and accessories for more than thirty years. The organization analysis, described below, is divided into the following sections: organizational structure, process management, routine management, and indicators management.

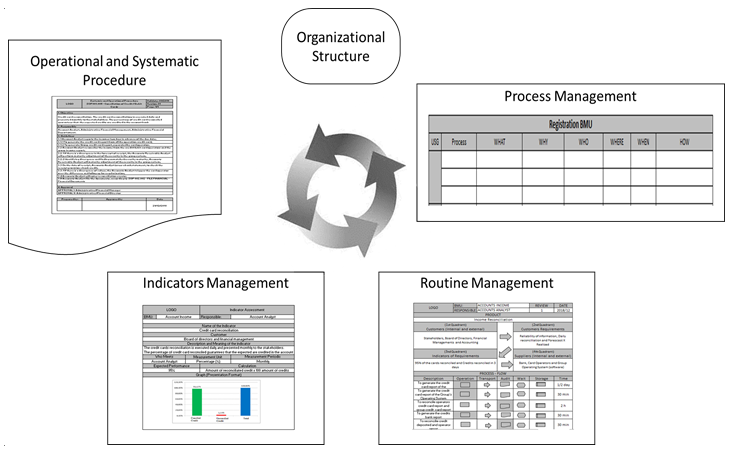

The organization has grown progressively in Northeast Brazil, becoming an exclusive franchisee of three popular fashion and cosmetic brands in this region. The organization had two main branches: Administration and Commercial, with the corresponding directors at the top. The commercial branch is responsible for coordinating the product orders with the three suppliers: store management activities, sales productivity, and marketing strategies. In general, because of the guidance and standards of the three franchises, it was able to work effectively.

However, the administration branch was too small to assure the management of the financial, logistics, human resources, technology, and legal departments. The company's strong commercial expertise was the reason for its growth, but the lack of internal control precluded the organization from making the practical analysis of the real state of its results, losing market opportunity and profitability. As a franchise, the organization has restrictions set by the franchisors such as the minimum stock of certain products and the fixed sale prices. The company, therefore, has a few options on how to control profitability: the sales strategy and operating costs.

Moreover, the division between the two branches was unclear: the relationship between the directors and staff was confused due to a lack of clear direction or instruction. In some cases, the work was divided based on friendship or confidence rather than an organizational structure. Additionally, both directors gave instructions to everyone, and it was unclear for the staff to which director they should report their activities. Moreover, the goals of each department were vague. On the above organizational structure, the departments did not have any defined process or team distribution. The organization was able to execute the requirements of the franchisors but did not have internal controls of its profitability and management process. Figure 2 demonstrates the above organizational chart of the organization. This study focuses on the administrative branch.

Figure 2. Former Organizational Structure

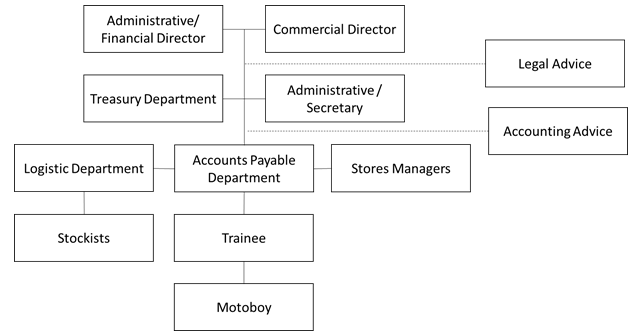

The proposed organizational structure takes into consideration the feedback system principles: each department receives an input from another department, processes its activities, and delivers an output to another department. It was also considered the required qualifications of the team. The feedback system allows specifying the process of each department sharing responsibilities without departing from their obligations. And this new organizational structure is closely related to the context in which it works, as reported by Pugh et al. (1969). Figure 3 represents the proposed organizational structure to elaborate the processes of the organization, and Table 1 describes the responsibilities of each position in the new organizational structure.

Figure 3. Current Organizational Structure

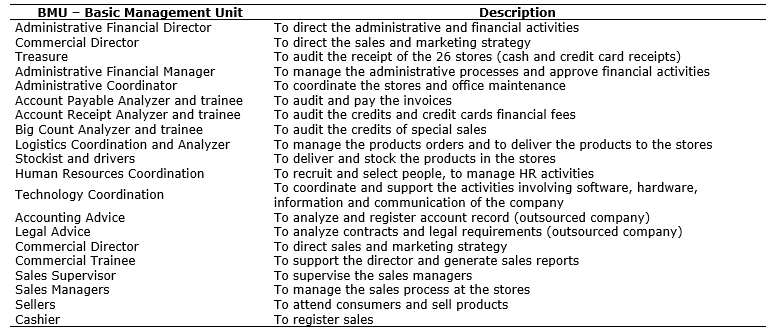

Table 1. Responsibilities of positions in new organizational chart

Furthermore, the technical skills and the required qualifications were analyzed for each position. Then, a recruitment company was contracted to select the best candidates to fill all the new positions. For a productive organizational change encompasses structure, strategy, style, skills, and, especially, the team (Waterman et al., 1980). Moreover, some of the former employees were resistant to the new responsibility and did not consider the value of the changes, which made them eventually leave the company.

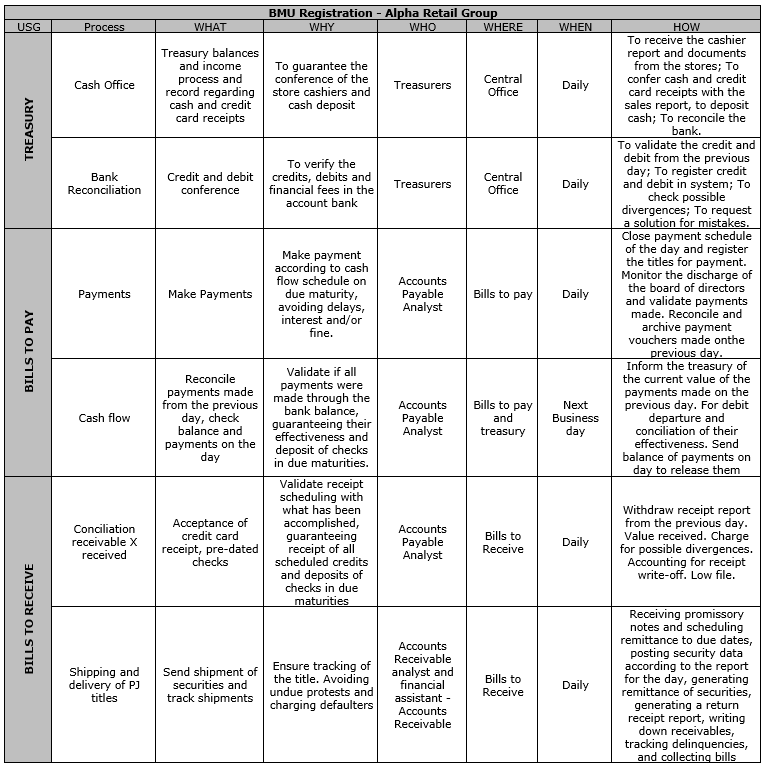

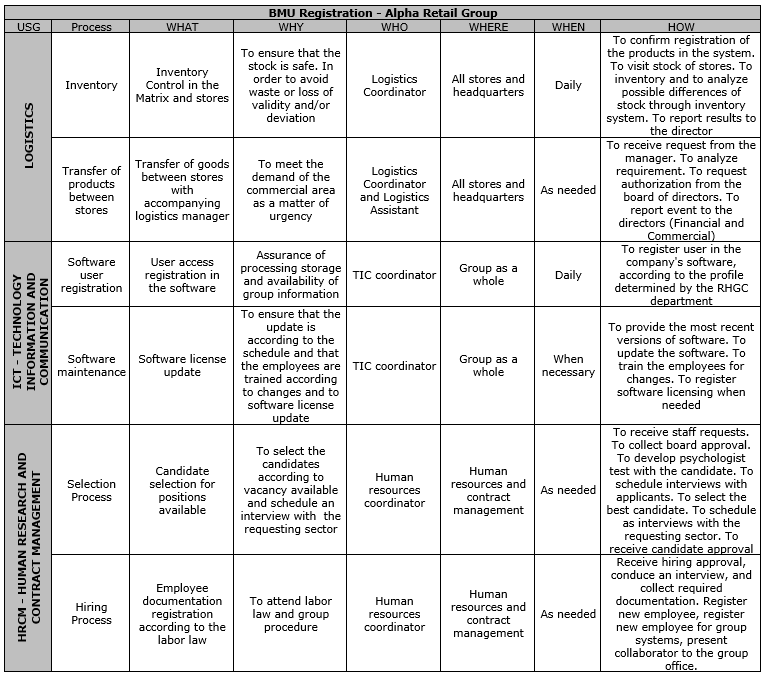

Following the new organizational structure, the next step is to identify a Basic Management Unit (BMU) for each department. The objective of BMU is to elaborate an individual organization management for each department, providing a clear understanding of the departments’ processes. The team would visualize its unit as a unique “company” that needs suppliers (information from another department) and generate a product delivery (information to another department). The team would have the feeling of being the owner and responsible for the results of its unit. Each department created its BMUs using the 5W1H tool (what, why, who, where, when, how). The eight BMUs registered for the organization is in Appendix A and B.

The Basic Management Unit identification provides an opportunity to evaluate individual activities and review their importance. This process has canceled diverse activities considered obsolete and has identified the necessity to elaborate new processes as well as it has relocated some activities to another department or BMU.

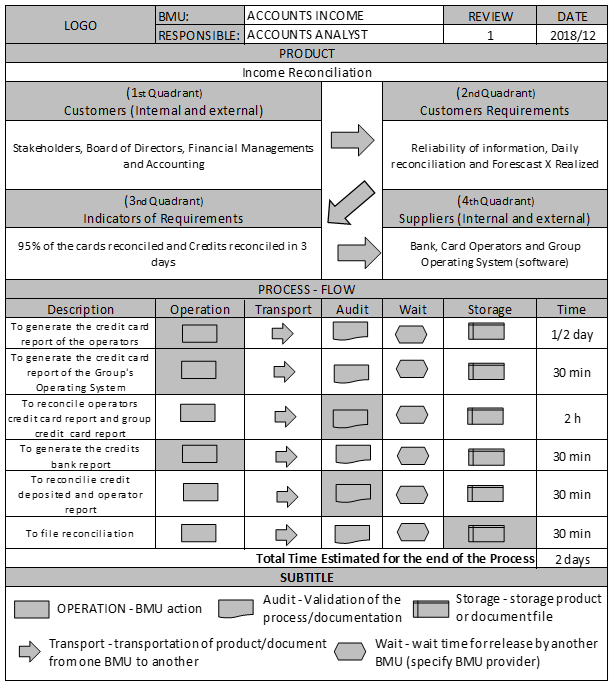

Following the BMUs analysis, the next step is to create the products of the BMU. Based on the initial analysis of each activity of the BMU, it is important to analyze in detail the workflow, the requirements, and the delivery of each activity, named product in this study. The idea of analyzing the activity as a product of the BMU is to visualize the BMU as a company and identify the “suppliers” (the department from which the BMU requires information) and the clients (the department to which the BMU will deliver information). This methodology creates a productive cycle where each BMU identifies the needs of the next BMU. This routine management provides a detailed workflow of the product of each BMU, evaluating the aspects that are impacted and impact another activity.

In this stage of the project, because of the level of details required, the participation of the board was significant because of the complicated process involved in this activity. Employees were required to do extra work, once they could not interrupt the daily operation and have an essential role in describing the activity in detail. Therefore, constant motivational incentive, reinforcing the importance of this step, becomes essential to the success of this stage of the project. Appendix C demonstrates one of the products designed by one of the departments of the case study.

Products provide an opportunity for each department to evaluate individual activities and the time spent to execute them. As a result, the BMUs identify their needs and how they need to deliver the activity. It is also possible to identify the connection among the BMUs and each one has the knowledge of its products and how they impact on the other BMUs. Communication is smoother and more precise between BMUs.

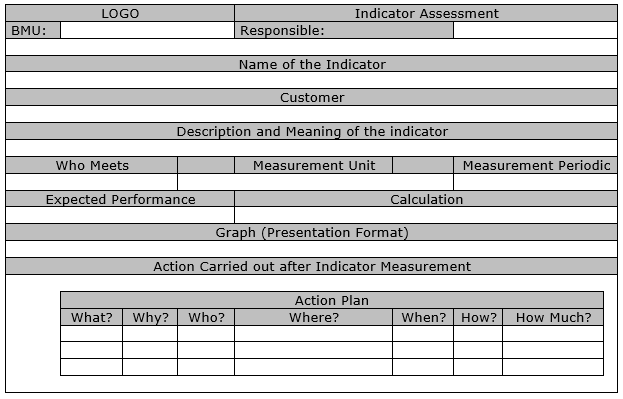

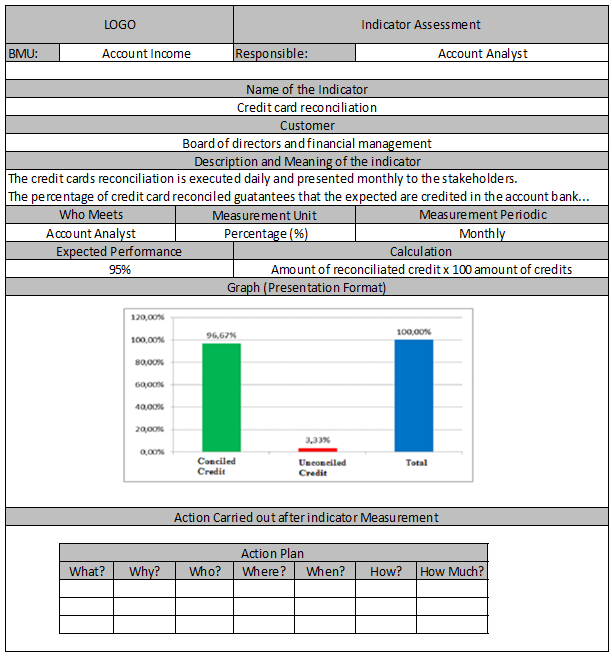

Following the BMU’s product identification, the next step is to identify how to assess the indicators and how to present their results to the stakeholders. Table 2 demonstrates the implemented form to identify the details of each indicator.

Table 2. Indicator Assessment Form

During the analysis of the indicator’s assessment, the team has a clear idea of how to evaluate the activity and what the company expects from them. Appendix D demonstrates one of the indicator assessments designed by the case study organization.

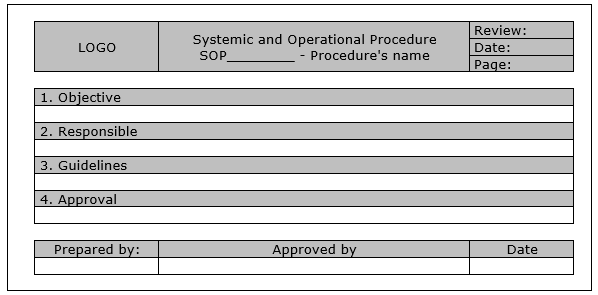

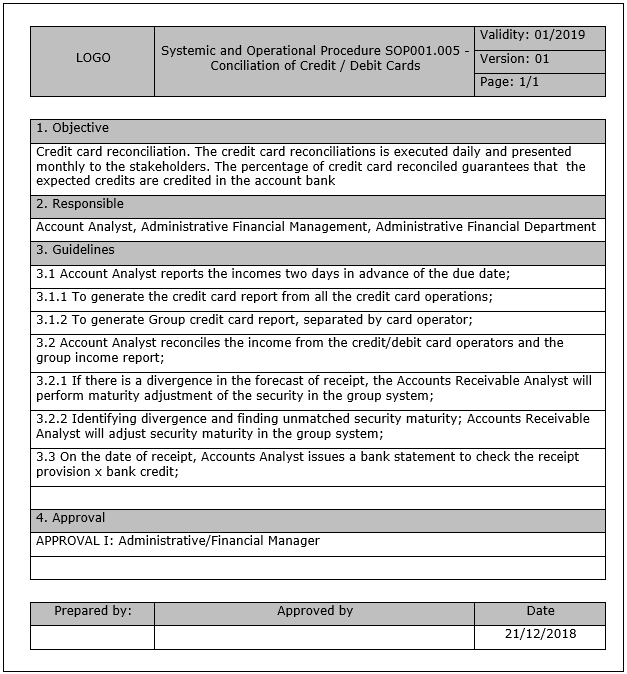

Following the underlying implementation, it is necessary to formalize the processes, so all the employees have access to the organization’s procedure. Moreover, the new employees have access to detailed and technical information on what they need to execute and are aware of the requirements of each activity. The official document of the organization follows the standard illustrated in Table 3, called SOP (Systemic and Operational Procedure), and Appendix E demonstrates one of the SOPs designed by the case study company.

Table 3. Systemic and Operational Procedure Form (SOP)

This step allows formalizing all the process of the organization. Furthermore, the documentation allowed training new employees, becoming the process clear to all the members.

The improvements seen in the case study company with the application of process standardization are close to those found by Wanzeler et al. (2010), in a furniture sector company. They pointed out that process standardization brought higher productivity for the company studied and provided even greater systematic and continuous control of operations.

Manchini (2019) points out in his studies the importance of measuring indicators and application in the management routine, and suggests, as an improvement to the studied company, the implementation of the complete PDCA cycle, for process management, indicator monitoring, and continuous improvement.

The results found by Moura and Nunes (2019) indicate that process standardization is efficient not only in the process itself but also in reducing costs and ensuring process reliability, which generates savings for the company that adopts this management model.

The methodology used to implement changes in a company is as important as the implemented tool, since the greatest difficulty is not its understanding or knowledge, but the expenditure and persistence in the implementation of the tool.

This article aims to demonstrate the methodology used to implement the ALPHA RETAIL GROUP’s strategic knowledge strengthening and the expected results of its implementation, aiming to standardize administrative processes for the continuous improvement of the quality of retail services and can be applied to retail companies in emerging countries.

ALPHA RETAIL GROUP managed the activities at the organizational level exclusively through the Senior Directors and had little or none coordination among its staff before the restructuring process. The organization did not have clear internal workflows and followed the processes imposed by the franchisors only to satisfy their requirements. This lack of management process generates confusion within employee tasks, re-work, and adverse effects on the results of the organization.

The methodology used to restructure the ALPHA RETAIL GROUP has demonstrated to be very efficient, resulting in increased motivation and involvement of the team, and improved the results of the organization.

However, although the implementation of the project was successful, it required the substantial participation of the board. It also provided stressful moments when the team needed to be changed, causing emotional stress to the current team.

The new structure drastically changed the operating management system of the organization. Store management and sales staff remain consistent and follow the same coordination mechanisms of the franchises. The most significant change is in the management of the activities at the organizational level, having an apparent distribution of the activities.

Previously, the departments did not have goals and explicit coordination. The new structure allowed the departments to have goals and assessment management for their indicators. The organizational structure, plan, execution, and control were the primordial and essential characteristics for implementing the entire project.

Reinforcing the importance of this research is necessary. An organization can follow this methodology to improve processes and management process. The methodology has shown to be efficient and provide excellent results in the management process, improving the results of the organization.

The main contribution of this research was through the case study, in which small, medium and large companies can make use of simple tools for daily improvement. It is believed that the results found were a consequence of the characteristics of the case study and cannot be generalized.

The check and action steps of the PDCA tool are significant so that the implementation of the restructuring project achieves its primary objective: to seek the continuous improvement and optimization of the processes executed by the Engineering Managers.

Monitoring allows Engineering Managers to ensure that processes met, and, at each presentation of results, can be evaluated utilizing a quantitative method, which can be improved, seeking more significant challenges.

To guarantee the success of the project, it is fundamental to keep the processes developed by analyzing the issues that need to be addressed through monitoring and corrective actions or improvements. Checking and acting are essential actions for the continuity of the project of continuous improvement and optimization of processes. Without this methodology executed by the managers, the continuity of the work implanted will be lost over time.

As a limitation, it should be highlighted the fact that this research was elaborated taking into consideration the specificities of the studied company and that the planning of the implementation of the necessary changes was made observing the needs of the company and its particularities. The proposed approach can be applied to other companies, provided that the specificities of each case are respected.

Since the beginning of this research, the application of the approach has faced many daily difficulties. The biggest one was related to the structuring of people. The group did not have a team that met the project requirements, which generated a greater expense at this stage and had to revise the implementation period, which initially lasted from one and a half to two years.

After structuring the team, the biggest difficulty was focusing on the implementation of the project stages, because, as there were no well-aligned processes, the daily routine consumed the time of all employees. It has always been necessary to carry out awareness and motivation work so that the project does not fall into disbelief or delay the sending of the necessary information for the elaboration of each process.

As a continuation of this research, it is suggested for the company:

As a continuation of this research, it is suggested to the academy:

Alotaibi, Y.; Liu, F. (2016).,“Survey of business process management: challenges and solutions”, Journal Enterprise Information Systems, Vol. 11, No. 8, pp. 1119-1153.

Brandão, I. F.; Diogenes, A. S. M.; Abreu, M. C. (2017), “Value allocation to stakeholder employees and its effect on the competitiveness of the banking sector”, Brazilian Journal of Business Management, Vol.19, No 64, pp.161-180.

Cesconeto, R. B. Guimarães Filho, L. P.; Bernardin, A. M. et al. (2014), “Use of quality tools for processes improvement in the flexible rod sector: the case study of a company in the personal hygiene sector”, Spacios Magazine, Vol. 35, No 8.

Chiarini, A.; Vagnoni, E. (2017), “Strategies for modern operations management: answers from European manufacturing companies”, Benchmarking: An International Journal, Vol. 24, No. 4, pp. 1065-1081.

Cohen, Y.; Rozenes, S. (2017), “Improving operational measures in a financial institute call center: a case study”, Brazilian Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. 204-209.

Deming W. E. (1982), Out of the Crisis, MIT Publishing, Cambridge, MA.

Falcão, L. M. A. A.; Jerônimo, T. B.; Melo, F. J. C. et al. (2017), “Using the SERVQUAL Model to Assessmall Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction”, Brazilian Journal of Operations and Production Management, Vol. 14, pp. 82-88.

Forno, A. J. D.; Forcellini, F. A.; Kipper, L. M. et al. (2016), “Method for evaluation via benchmarking of the lean product development process: Multiple case studies of Brazilian companies”, Benchmarking: An International Journal, Vol. 23, No. 4, pp. 792-816.

Geramian, A.; Shahin, A.; Bandarrigian, S. et al. (2017), “Proposing a two-criterion quality loss function using critical process capability indices: A case study in heart emergency services”, Benchmarking: An International Journal, Vol. 24, No. 2, pp. 384-402.

Gil, A. C. (2010), Como elaborar projetos de pesquisa, Atlas, Rio de Janeiro.

Gorchels, L. (2003), “Transitioning from engineering to product management”, Engineering Management Journal, Vol. 15, No. 4, pp. 40-47.

Gorenflo, G.; Moran, J. W. (2009), The ABCs of PDCA, Accreditation Coalition, Minnesota, USA.

Harmon, P. (2007), Business Process Change – A Guide for business Managers and BPM and Six Sigma Professionals, 2 ed., Burlington-USA, Morgan Kaufmann Publishers.

Hoang, H. H.; Jung, J. J.; Tran, C. P. (2013), “Ontology- based approaches for cross-enterprise collaboration: a literature review on semantic business process management”, Journal Enterprise Information Systems, Vol. 8, No. 6, pp. 648-664.

Hung, R. Y. (2011), “Business process management as competitive advantage: a review and empirical study”, Journal Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 21-40.

Idzikowska, T. (2017), “European Standardization for the management of space-related projects”, Scientific Journal of Silesian University of Technology, Vol. 95, pp. 55-65.

Imai, M. (1986), Kaizen: The Key to Japan's Competitive Success, McGraw-Hill Publishing Company, New York.

Lapchak, P.; Zhang, J. (2018). “Data Standardization and Quality Management”. Translational Stroke Research, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 4-8.

Liker, J. K.; Meier, D. P. (2007), Toyota Talent: Developing Your People the Toyota Way, Hardcover, New York.

Manchini, V. V. (2019), “Case study: use of process performance indicators in the management of cotton cultivars production”, Online Production Magazine, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 249-273.

March, J. G.; Simon, H. A. (1958), Organizations, Wiley, New York, NY.

McMullen, J. S.; Kier, A. S. (2017), “You don’t have to be an entrepreneur to be entrepreneurial: The unique role imaginativeness in new venture ideation”, Business Horizon, Vol. 60, No. 4, pp. 455-462.

Miguel, P. A. C. (2018), Metodologia de Pesquisa em Engenharia de Produção e Gestão de Operações, Elsevier.

Moura, C.R., Nunes, C. C. (2019), “Padronização de Processo na Linha de Montagem de Uma Empresa Multinacional: Um Estudo de Caso”, GEPROS: Gestão da Produção, Operações e Sistemas, Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. 282-300.

Pellicer, E.; Correa, C. L.; Yepes, V. et al. (2012), “Organization improvement through standardization of the innovation process in construction firms”, Engineering Management Journal, Vol. 24, No. 2, pp. 40-53.

Perevozova, I.; Babenko, V.; Kondur, O. et al. (2019), “Financial support for the competitiveness of employees in the mining industry”, SHS Web of Conferences, Vol. 65, 01001.

Porter, M. E. (1979), How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy, Havard Business Review, Harvard Business School Press, Mar-Apr.

Pugh, D. S., Hickson, D. J., Hinings, C. R. et al. (1969), “The context of organization structures”, Administrative science quarterly, Vol. 14, No. 1.

Purosottama, A.; Ardianto, A. (2019), “The dimension of employer branding: attracting talented employees to leverage organizational competitiveness”. Jurnal Aplikasi Manajemen, Vol. 17, No. 1.

Ricco, R.; Guerci, M. (2014), “Diversity challenge: An integrated process to bridge the ‘implementation gap’”, Business Horizon, Vol. 57, No. 2, pp. 235-245.

Roland, P. (2009), The Process Architect: The Smart Role in Business Process Management, New York.

Ross, A. (2016), “Establishing a system for innovation in a professional services firm”, Business Horizon, Vol. 59, No. 2, pp. 137-147.

Shingo, S. (1981), Study of Toyota Production System from Industrial Engineering Viewpoint (Tokyo, Japan Management Association).

Silva Júnior, O.; Lopes, L. A.; Bergmann, U. (2011), “A Free Geographic Information System as a Tool for Multi-Depot Vehicle Routing”, Brazilian Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 103-120.

Silva, A. S.; Medeiros, C. F.; Vieira, R. K. (2017), “Cleaner Production and PDCA Cycle: Practical Application for Reducing the Cans Loss Index in a Beverage Company”, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 150, No. 1, pp. 324-338.

Simon, H. A. (1947), Administrative Behavior, Macmillan, New York.

Singh, J.; Singh, H. (2015), “Continuous improvement philosophy – literature review and directions”, Benchmarking: An International Journal, Vol. 22, No. 1, pp. 75-119.

Skrynkovskyy, R.; Pawlowski, G.; Sytar, L. (2017), “Development of Tools for Ensuring the Quality of Labor Potential of Industrial Enterprises, Path of Science: International Electronic Scientific Journal, Vol. 3, No. 9, pp. 3009-3018.

Slack, N.; Chambers, S.; Johnston, R. (2010), Operations Management, Sixth Ed., Prentice Hall.

Styhre, A. (2017), “Ravaisson, Simondon, and constitution of routine action: organization routines as habit and individuation”, Journal Culture and Organization, Vol. 23, No. 1, pp. 1-12.

Sumarto, S. (2017), “Equalization and Standardization of Management of Education of Madrasah” Hunafa: Jurnal Studia Islamika. Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 117-139.

Wang, H.; Wang,L.; Liu, C. (2018), “Employee Competitive Attitude and Competitive Behavior Promote Job-Crafting and Performance: A Two-Component Dynamic Model”, Frontiers in Psychology, Nov. 21.

Wanzeler, M. D. S., Ferreira, L. M. L., Santos, Y. B. I. (2010), Process standardization in a furniture company: a case study. National Meeting Of Production Engineering, Vol. 30, pp. 1-14.

Waterman Jr, R. H., Peters, T. J., Phillips, J. R. (1980), Structure is not organization, Business horizons, Vol. 23, No. 3, pp. 14-26.

Watson, L. A.; Tytula, T. P. (1996), “Process Improvement: Reengineering spacelab mission requirements flow”. Engineering Management Journal, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 21-26.

Wright, C.; Sturdy, A.; Wylie, N. (2012), “Management innovation through standardization: Consultants as standardizers of organizational practice”, Research Policy, Vol. 41, No. 3, pp. 652-662.

Yin, R. K. (2017), Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, SAGE Publications.

Received: 11 Mar 2019

Approved: 17 Oct 2019

DOI: 10.14488/BJOPM.2019.v16.n4.a15

How to cite: Espíndola, S. C. N. L.; Albuquerque, A. P. G.; Xavier, L. A. et al. (2019), “Standardization of administrative processes: a case study using continuous improvement tool”, Brazilian Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 16, No. 4, pp. 706-723, available from: https://bjopm.emnuvens.com.br/bjopm/article/view/823 (access year month day).