Fluminense Federal University – UFF, Niterói, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Fluminense Federal University – UFF, Niterói, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Fluminense Federal University – UFF, Niterói, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Goal: Contribute to the academic literature on the theme social license to operate, of the perception and experience of professionals from Brazilian extractive companies involved in the process.

Design / Methodology / Approach: In-depth interviews with professionals with great experience in community relations processes, evaluating their perception regarding social license to operate, especially with the companies they work.

Results: Two products are presented: a) illustration with a conceptual analysis of the terms related to the social license process to operate; b) basic model of community relationship based on recommendations of the professionals to obtain and maintain the social license to operate and the literature visited.

Limitations of the investigation: the survey heard 12 professionals with extensive experience in the extractive sector in Brazilian companies to understand how companies act and their perceptions regarding Social License to Operate (SLO). However, other important actors, such as communities, Nonprofit Organizations and community leaders were not heard throughout the research, and a corporate vision was presented throughout the article, but only against the literary review.

Practical implications: It presents a consistent picture regarding the behavior of companies in relation to SLO. It allows a better understanding of the relationship of concepts and terms that overlap in company practice and proposes a community relationship management model.

Originality / Value: The research brings an important contribution to the academic literature, when evaluating, from interviews with professionals in the extractive industry involved in the management of community relations, the way Brazilian extractive companies operate in this segment and the understanding with regard to SLO.

Keywords: Community Relationship; Stakeholder Management; Corporate Social Responsibility; Social License to Operate; Extractive Industry.

The business-oriented perspective that privileges exclusively the investors does not seem to be suitable anymore for a new reality where large corporations do not limit their efforts to efficiently producing goods or services or maximizing profits. Companies are giving more importance to impact management, ethical and transparent behavior, and sustainable business-side performance.

On the other hand, communities based on the use of new technologies, with the capacity to act in a network and agility in the communication processes, are more representative and present themselves as relevant actors in the current social outlook. The Social License to Operate (SLO) concept emerges in this context.

The origin of the term "Social License to Operate" is related to the expansion of the mining industry in Canada, more specifically in the discussions on social conflicts that guided this period.

Since then, the term SLO is linked to the mining industry. The visited literature shows this close relation between the extractive segment and the SLO concept, a relation that is justified by some aspects, such as the impacts caused by operations and the activities of companies in this segment and the great expectation generated along the communities in the places where they are inserted or act.

Abdala (2016) ponders that mining projects are perceived with distrust on the part of the communities and the local leaderships. The author stresses that these large projects affect the territory where they are installed economically, environmentally, and socially.

Regional Association of Oil, Gas and Biofuels Sector in Latin America and the Caribbean (Asociación Regional de Empresas del Sector Petróleo, Gás y Biocombustibles en Latinoamérica Y el Caribe – Arpel, 2016) is concerned about the impact of the activities of oil companies, highlighting the great challenge for the oil and gas industry to sustain a good reputation due to the characteristics of the activities carried out and the conditions of its surroundings. The organization also emphasizes the need for greater attention in the management of environmental, socioeconomic, cultural and political risks and impacts due to complex situations in environmentally sensitive, socioeconomically fragile and politically isolated areas.

The World Bank and the International Finance Corporation (2002) highlights the impact capacity in mining activities into the environment and also in local community’s social and cultural aspects, especially on indigenous people.

In this context, the search for sustainability and social responsibility performance are strategic and vital for the development of the company's activities and operations.

According to McMahon and Remy (2001), legal licenses are no longer sufficient and adequate. Companies must obtain a social license that depends on processes of consultation, local participation and, above all, a constant and strong dialogue between community, corporation and government.

In order to avoid any difficulty in understanding, SLO is not related to the process of environmental licensing imposed by Brazilian or by any other formal process of obtaining documents or complying with compliance for the installation and operation of units.

Bowen et al. (2010) present the question of legitimacy as a premise for the corporation’s actions in communities where it operates, listing the benefits and competitive advantages of such procedures, as the improvement of its risk management gain greater credibility with its stakeholders and more effectiveness in promoting its activities within the community.

In companies that operate in the extractive sector, the impacts caused to communities become more evident and more significant, as evidenced even in the documents of the institutions that represent the companies in this segment, as the Brazilian Institute of Mining (Instituto Brasileiro de Mineração - IBRAM).

IBRAM (2014) highlights the issue of generating impacts throughout the mines’ life cycle, especially with communities. The impacts (positive and negative, direct and indirect) are present from the prospecting to the post-closure phase.

The close relationship between SLO with the extractive segment directed this research. Professionals from extractive companies with outstanding performance in activities with communities were identified and selected to evaluate how Brazilian extractive companies have been recognizing and implementing the theme; the performance of their companies; the role of the SLO; and the corporate and marketing motivations that implicate the concept. Gaviria (2015) reveals that, even if there are not many theoretical or analytical works on SLO in the business sciences, it is noticeable the growing interest on the subject by the mining industry and by some professional and academic circles.

The research aims at understanding, based on a qualitative research, how Brazilian extractive companies relate to the communities of the location where they operate, and in what way SLO processes interfere in this relationship.

The state of the practice is focused on semi-structured interviews with professionals involved with relationship processes with the communities and other stakeholders of Brazilian extractive companies (defined as focus of research). The analysis of the state of the piece, however, was done without borders, and the literary revision was not restricted to Brazilian national productions and involved international bibliography.

The bibliographic review was carried out from the keywords highlighted for this research, handpicking articles, documents (theses and dissertations), norms and technical instructions in databases, such as academic platforms, technical libraries, and corporate libraries.

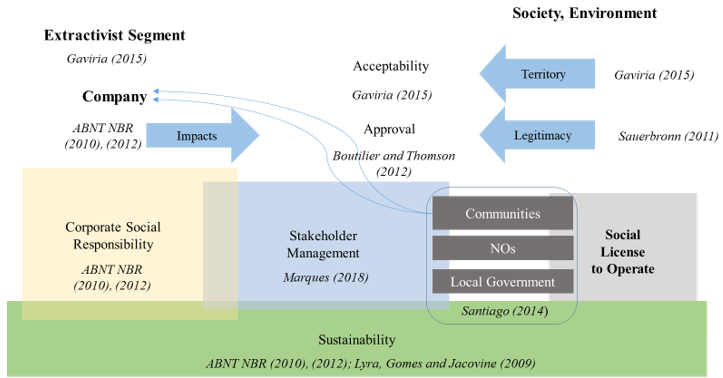

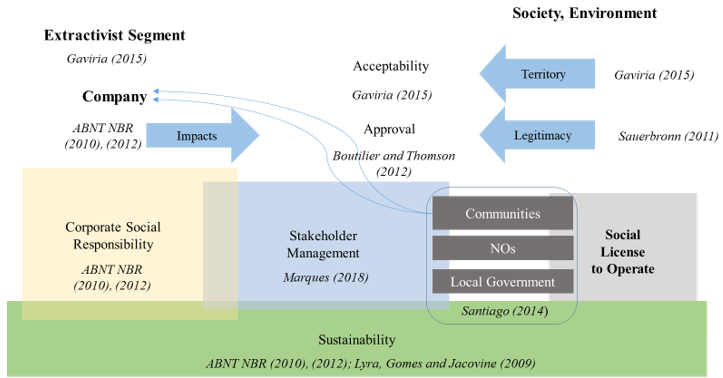

Therefore, the Boolean Model was used to get the articles on www.scopus.com: (Community relations) AND (Social license to operate) OR (Corporate social responsibility) OR (Stakeholder management). These Key words are connected with the thematic area. In this case, the researcher has followed the framework in Figure 1, below, after he has gotten the articles from the SCOPUS database.

Figure 1. Literature review logical framework

Source: Faria et al., 2018.

To select the professionals for the intentional sampling, the criterion was a minimum of two years of professional performance with community relations and at least four years with related areas, such as social responsibility and institutional relations. A sample was defined for convenience: specialists from the areas related to the topic, ten professionals of extractive companies (oil, gas and mining companies) and two consultants who work in extractive sectors, especially in mining and oil and gas companies.

In relation to the professional experience, two questions were raised: quantity of time of activity in the current company and quantity of time of professional activities with the research theme (self-declaratory form based on personal understanding about the subject's experience).

As a result, the ten interviewed professionals that work in extractive companies have more than five years of experience in the company where they work and the two consultants work routinely with companies of this sector, proving the consistency of the sample (nine of the interviewed indicate between six and twenty years of experience).

The interviewees are settled in seven different cities in three different regions of Brazil: Southeast, Northeast, and North. To conduct interviews with professionals in different locations, a variety of technological resources were used, such as video and teleconferencing. The interviews with these experts were conducted in 2017. Thus, the interviews were conducted in Portuguese. The translation was performed by the authors.

The interview script was designed to obtain information from interviewees on how the Brazilian extractive companies recognize and treat the SLO concept and activity, the means used for it, and the professionals' perception of the subject and their relationships, main models, and references.

The main points discussed during the interview are list below:

The technique employed for the treatment of the interviews was content analysis. According to Soares et al. (2011, p.5), this methodology was treated as a way of analyzing and interpreting texts and it "has gained scientific relevance, as it was improved as a technique applied in the most diverse sciences, including social sciences".

The current productive and economic model has generated serious social and environmental problems, exposed by different authors and evidenced in different ways by different publics.

Marques et al. (2018) indicates that organizations need to create structured and strategic procedures to manage their stakeholders, considering the dynamics for this relationship.

Santiago and Demajorovic (2014) indicate that conventional approaches based on legal compliance are no longer sufficient to legitimate the presence, operations and actions of companies. The Official authorization of state instances no longer guarantee companies plain fulfillment of their activities.

For Werneck (2013, p. 108), SLO “arises in this scenario and presents as product, precisely, the legitimacy, or acceptance and support that a company receives from its stakeholders”. Once obtained, SLO must be managed to ensure its maintenance throughout the entire business operation process. Werneck highlights that defining assessment forms and SLO management models is a constant challenge for companies, ratifying the importance of this research.

Two decades separate the first mention of the term Social License to Operate and the present day, that is, a concept under construction and the visited literature proves that it is a very young science area, where there is still an expressive variation of perceptions, definitions, and approaches.

Gaviria (2015) emphasizes the difficulty in setting a definition for the term and indicate that the expression, together with other practices associated with it, has been incorporated by the rhetoric of institutions, foundations and companies.

The author observes a growing number of mining companies associating the term SLO with their discourses related to community relations policies and social programs and to the terms "social responsibility" (“SR”), "private social investment", and "sustainability".

In fact, the SLO rarely presents itself far from terms and initiatives of social responsibility, sustainability, stakeholder management, and relationship with communities or related subjects, such as human rights, ethics, transparency and impact management. Pardini (2007, p. 47) goes on to propose that "the conceptual framework of what would become social responsibility could be associated with the history of organizations' relationships with communities directly affected by their activities."

The Brazilian Association of Technical Standards (Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas – ABNT, 2010, p. 63) draws a clear relationship between sustainable development and aspects related to SLO: "Community involvement and development is an integral part of sustainable development as a whole."

The ISO 26000 standard presents a definition on Social Responsibility considered as basis by many companies and by different authors. In it, by valuing the responsibility of an organization in face of its impacts and decisions, ABNT emphasizes an inherent value to the SLO process: the necessary action by companies in relation to the impacts caused by their facilities, operations, activities and decisions that evidences the relationship between CSR and SLO.

Oliveira et al. (2015) also highlight the need for a change in the role of companies, the importance of management over its impacts, the ethical and transparent behavior, and the sustainable performance.

Sauerbronn (2011, p. 46) points out that CSR "has dedicated itself to providing answers to the questionings of society and justifying or legitimizing business activities", bringing an essential aspect of the SLO concept, legitimacy, which is necessary for a company to establish itself and operate in different regions, in the midst of already established cultural, historical and social aspects.

Maggiolini and Naninni (2010) explain that the current transition, in which we are leaving the industrial society and getting into to a “post-modern” society (one that brings techno-economical transformations, service economy, information technologies, and consumer’s supremacy on producer), creates change in the values system and thus the request for CSR and business ethics.

Ruggie (2014) claims that the relationship between large transnational corporation results and the social and economic conditions of society, especially the locations where these companies operate, are no longer acceptable in a society that respects human rights. Ruggie reinforces that the citizens and communities affected by these companies have been using the human rights speech (that guarantees the dignity and value of any person anywhere), expressing grievances, desires, and resistances.

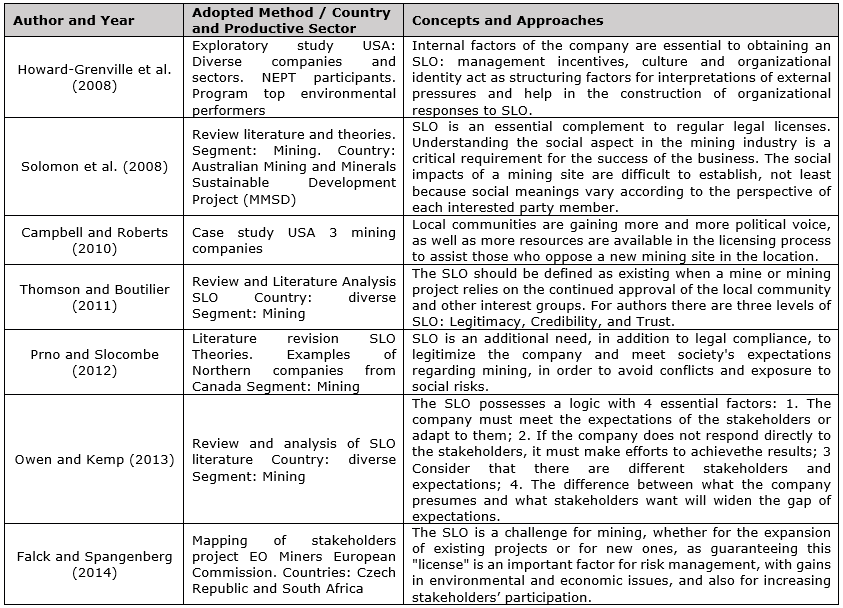

The SLO acts precisely at this distance between the corporative attitude and conduct of the companies and the resilience of society, especially of the communities in the search of guaranteeing their rights. Different definitions and approaches (by relevant authors) of SLO are listed by Santiago and Demajorovic (2014) in Table 1.

Table 1. Social License to Operate: Concepts and Approaches

Source: Santiago and Demajorovic (2014, p.7)

Table 1 presents the diversity and multiplicity of the concept and allows a better understanding of the complexity of the term and the perception of the main points related to SLO. One of the points (basic for understanding the concept) is the importance of establishing a continuous relationship between companies and their stakeholders, highlighting the interested community part.

For a better understanding of the concept of community, a brief presentation of the theme and the term is required. According to Sauerbronn (2011, p. 48), it presents an opportune view within the universe of social responsibility that holds important relations with the subject of SLO, with an adequate definition for the objectives of this article: “a specific group of individuals whose social issues arouse the interest of the company, regardless of the location or territory it occupies”.

Gaviria (2015, p. 141) points out "community" as a stakeholder reference in the SLO process, when defining SLO as "a kind of approval of the community in relation to the operations of a particular company". Boutilier et al. (2012, p.2) present as an SLO definition "the community's perceptions about the acceptability of a company and its operations in the region", also characterizing this stakeholder as the protagonist of the process.

Throughout the different definitions of the SLO concept, presented in Table 1, it is clear that it is a non-formal process, an act of consent on the part of certain social actors, especially communities, environmentalists and government, which is met with criticism by some segments and authors, who understand that the term is confused with formal processes established by entities of the state to settle and perform in a certain locality.

The absence a process to obtain it, the way it is used to maintain existing power imbalances in the relationship, and the ambiguity of the expression and its binary nature are some arguments used by the critics of the use of the term social license.

Garnett et al. (2018, p. 734) respond: “social license captures a more realistic application of the term: the tacit permission of civil society for an activity to occur or continue, so that the state has the political confidence to grant legal rights”. The term is appropriate to the practical reality of the companies’ activities and the negotiating power achieved by civil society and by the communities in particular.

The use of the term "license" demonstrates the necessary flexibility and the recognition by companies of the power of civil society to defend their rights before installation, activities, and operations of a company.

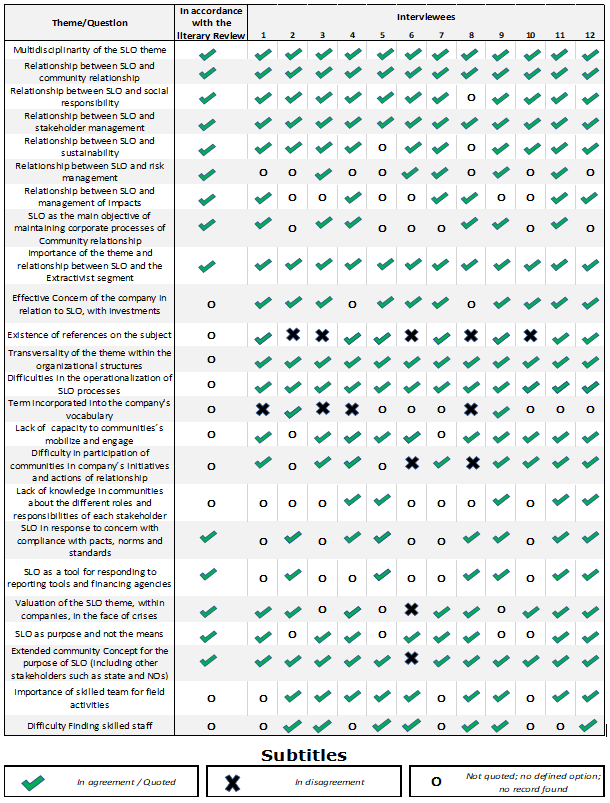

The content of the interviews was analyzed in such a way as to allow the quantitative understanding of the interviewees' agreement, knowledge or favorability or otherwise on certain subjects. In addition, there was the qualitative analysis that indicated the key information, points, references, models, and more important processes.

It is possible to identify a certain unity on the part of the interviewees about the subjects analyzed. It is also worth noting the important contribution of the interviewees regarding subjects, perceptions, practical aspects of SLO not identified in the literary review, as can be confirmed in Table 2, presented below:

Table 2. Content analysis (interviews)

Source: Author

Throughout the interviews, the relationship between SLO and the concepts or activities of community relationship, CSR, sustainability, and stakeholder management was clear, according to the interviewees who highlighted the relationship between the terms.

"Community relations, social responsibility, sustainable development, social license to operate and stakeholder management are the same process. It is impossible to see these items dissociated”. (Interviewee 9)

There was unanimity among the interviewees in terms of the likeness of SLO with the community relationship activity. Six of the interviewees, or 50% of the sample, spontaneously indicated that SLO is the purpose, the main objective for maintaining a corporate process of relationship with the communities. This aspect is of particular relevance because it demonstrates the importance of the theme for companies.

"I think SLO is something that is fundamental when we deal with Community Relations, because, in the end, what you are looking for is this; what you are looking for is the endorsement of those communities so that you can carry out your activities, which is fundamental”. (Interviewee 3)

Santiago and Demajorovic (2014) agree by defining the SLO as the license earned when a company relies on the approval and acceptance of the community and other groups of interest continuously involved in their projects. The objective presented in the guidelines of the company studied.

The treatment of interferences and impacts caused by the company in the environment and in the communities where the company operates is indicated as an important activity of community management relationship and is considered an inherent process in the management of social responsibility.

The peculiarities of the extractive sector were questioned to the interviewees, in order to better understand the importance of the theme for the companies in this segment.

It is clearly noticed that the SLO perception among the interviewees converges towards what the literary review points to: the extractive segment, due to its characteristics, has specific problems and demands that require a strategic corporate action in the communities, a group of people directly affected by its projects and operations, where SLO is a strategic component necessary to carry out the operations and activities of the company.

"In extractive companies, the link, the appeal to its neighbors, is fundamental. Community relationship is the flagship of the "company" within the SR". (Interviewee 9)

There were also spontaneous comments, not stimulated by specific questions, regarding the peculiarities of the extractive sector, ratifying the very specific characteristics of the segment, especially regarding its exploration and production processes, since these processes depend on the location related to the availability of resources and logistics means for their disposal, refining, and distribution.

“We will always be working with communities in specific locations, in specific biomes. So, there is this interaction, especially in the area of exploration and production where the company operates”. (Interviewee 2)

Another controversial issue is the perception of respondents in terms of the recognition by the companies of the importance of SLO, which, however, does not mean effectively the managerial sponsorship for the development of this activity. Many interviewees point out that although there is, in fact, this concern and resources are foreseen for this, they still find resistance on the part of the managements to realize the activities related to SLO and to community relationship.

It was verified by the interviewees that the managers who value the most, who care most and sponsor the corporate relationship with the communities are those who have already experienced crisis situations or those who live with more organized communities and social actors, articulated with greater power mobilization.

Even considering the great experience on the subject of the professionals interviewed, the questioning of possible references (orientations, norms, processes, and experiences of other companies) did not obtain any great prominence among the answers of the interviewees.

"We do not see a specific benchmarking model. We study and do not find anything of great value. We have developed a model of our own, based on dialogue”. (Interviewee 10)

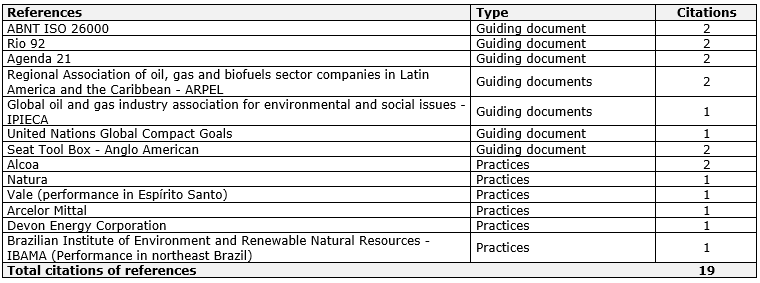

Although they were free to quote companies, organizations, norms, and models, only 19 references were cited by the interviewees (showed at Table 3), proving the absence of great highlights which ratifies the difficulty of carrying out the present study and its importance. Among the professionals, five had no highlights to mention or did not remember one. They confirm the need for a bigger technical and scientific literature on the subject.

"[…] it is a very recent science, without enough time to mature certainties, models and standards”. (Interviewee 3)

There were records of unsuccessful models and experiences to avoid, such as the 2015’s accident in the city of Mariana with the company Samarco and a curious case of the company Vale in its operations in Pará. The same company, Vale, was highlighted as a positive case for its work in Espírito Santo.

The most remembered initiatives obtained at most two quotes from the professionals interviewed, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Highlighting Models / Cases Benchmarking

Source: Author

Just as there are no reference models, it was also impossible to find uniformity within companies as the way they manage the activities in the communities to obtain and maintain SLO, not being possible to identify alignment as the sector or area responsible for the activities inherent to the process.

"CSR, in Brazil, was born, generally within the structures of Communication. CSR works with reputation and image, an obvious connection with communication." (Interviewee 8)

Among the models there are many variations on the definition of the area responsible for the activity: Communication, Social Responsibility and Health, and Safety and Environment (HSE) are the most common, but other models were cited as the case of a social responsibility area, responsible for part of the community relationship activities within the company, subordinated to Social Communication management, with other activities related to the theme being carried out in other areas of the company, as HSE.

Another model found presents different attributions under the same management as social responsibility; environment (licensing processes); HR (hiring staff); communication; institutional relations; press office; environmental investments; social area; and management.

It was also mentioned a curious model of a company whose proposed organizational structure varies with total autonomy and independence of each unit.

"Each unit has a model. Even structural, organizational”. (Interviewee 11)

Although professionals recognize the interdisciplinarity of the subject and companies have different areas dealing with it, this factor becomes a problem, an obstacle to good relationships with communities. The lack of a greater alignment between the areas generates overlapping of resources and activities and difficulties in unifying the discourse and the communication together with the communities.

This lack of alignment on how the theme is managed is justified, in large part by the wide range of activities that make up the routine of community relations activities, treated in both the visited literature and in the interviews as an interdisciplinary theme. Its peculiarities and difficulties were highlighted by all the interviewees.

An important factor emphasized during the interviews – that was not identified in the literary review – was the importance of teams qualified to perform fieldwork.

As an exception, it is worth noting Bebbington and Wilson’s (2018) perception on the subject presented at a congress of the Society of Petroleum Engineers, indicating the importance of professionals that play the role of developing and maintaining relationships with communities around the sites of their operations for companies. Besides the essential contribution to obtain and maintain SLO, the possibility to provide local knowledge that favors the company risks management and uncertainties, and the contribution to the company’s international standards implementation, “they are a familiar and accessible face with whom community members can raise concerns, perceive opportunities, and resolve grievances”.

The continuity and frequency of this work with the Community (and in it) are raised to the condition of fundamental to the success of the community relationship and obtaining and maintaining the SLO.

Bebbington and Wilson (2018) agree, indicating that the role of this professional is not clearly understood in the oil and gas industry, despite the value they bring to the relationship with communities nearest assets and projects, their critical part in the management of social impacts, and the mitigation of material non-technical risks.

The best practices manual, international standards, and corporate policies, they say, focus on the process and frequently underplay the contribution of these professionals to the interface between corporate and community relationships.

To carry out this activity, the importance of qualifying the teams to perform fieldwork was highlighted. The interviewees regretted the difficulty in finding skilled labor and stressed not knowing the difficulty in forming a professional with the profile, characteristics and knowledge necessary to accomplish this activity. There is no knowledge of the existence of a course that offers such training.

Another point highlighted by the interviewees is related to the little power of mobilization and a culture of fighting protests for rights that is not mature yet, the lack of knowledge of the social role of each actor within the territory, and of their rights and duties in Brazil compared to other countries.

“It lacks clarity from the community and different social actors about their roles in the process”. (Interviewee 9)

This behavior of less effective participation in their citizen routine is perceived by the interviewees as one of the factors that drive unit managers to value the community relationship less.

Other relevant aspects, from the corporate point of view, related to obtaining the legitimacy to act and the SLO maintenance identified by the interviewees are reporting tools, external pressure as signatures of pacts and compliance to norms, and, ultimately, the search for financing on an advantageous basis (usually linked to the previous ones).

"I see that CSR thrives in activities to meet standards and to achieve good results in terms of image and reputation and to seek funding, complying to reporting tools.” (Interviewee 2)

However, the clear perception among the professionals heard in terms of SLO is the importance of making community consent a detail of the process, not its primary goal. Although they recognize the corporate importance of obtaining a license to operate, they understand that this legitimization is a natural process, when there is the legitimate concern of the company regarding ethical and transparent behavior and the management of impacts and risks, as well as concern for local territorial development.

If companies with greater locational flexibility are able to condition or bargain their installation with advantages and benefits, extractivist companies, with their rigidity of location, are restricted to established and/or existing socio-political conditions. As a consequence of these restrictions of choice, these companies must resort to mechanisms of social and political intervention in this space where social license makes sense. Companies that want to explore the resources of certain locations where they are available must undergo locational rigidity that makes them relatively dependent on access to these lands, on established regulations, and on time and cost requirements.

“The relationship differs for each location. It depends on the amount of information, the organization of the communities, the existing living conditions, and if it is already a tradition for the people and community”. (Interviewee 12)

Mayes (2015, p. S110) emphasizes in his research the importance given to the SLO theme in the mining industry. The author indicates that SLO is not only related to the success of the industry, but also to its survival, highlighting the “complications generated by the involvement of ethical investment funds, buyers, and customers worried about distancing themselves from unethical business practices”. There was also a growing number of projects interrupted and which presented problems in their progress due to community mobilization.

This means that the presence (or absence) of SLO in the community can have broad consequences, particularly in terms of access to new resources and sales reduction, characterizing the relationship between obtaining or not an SLO and possible losses or financial losses for companies. The interviewees make this corporate concern clear, even indicating SLO as the main objective of engaging with communities.

The Business for Social Responsibility (BSR, 2016), presented on its home page (www.bsr.org) as “the global nonprofit organization that works with its network of more than 250 member companies and other partners to build just and sustainable world”, concludes in its study “The Future of Stakeholder Engagement”. This is because, when carried out efficiently and strategically, stakeholder engagement directly affects the economy of resources. The organization emphasizes that studies prove that the corporate process of community relationship is able to make the company financially more resilient due to the ability to anticipate risks and opportunities: “Companies that are more aware of stakeholder interests are more likely to avoid crises because they are better able to anticipate risks and opportunities”.

Santiago and Demajorovic (2014, p.260) Highlight the achievement of SLO as the objective of stakeholder engagement, treating it as a specificity in the midst of other purposes.

The study also claims that nowadays there is enough evidence “to resolve any outstanding doubts about whether stakeholder engagement is an inherently valuable exercise”.

Davis and Frank (2014, p.39) justify this concern by presenting recent calculations of mining industry business costs from conflicts with local communities, showing that the most substantial arise from “lost value related to future projects, expansion plans, or sales that do not go through”.

The perception of the interviewed professionals stands out in this sense, emphasizing that the management sponsorship for the search for SLO is perceived more clearly in units, or with managers who have already dealt with community crises. They also point out that this is an initiative whose value is clearly perceived only when it fails, precisely when conflicts arise, capable of interrupting operations, processes and activities of the company.

However, Gaviria (2015, p.139) brings to the debate a new point of view when he states that "social license to operate appears, without a doubt, as an active business bet of socio-political intervention for the conditioning of territories to the needs of extractive capital". Adopting a more critical tone regarding the SLO process, the author classifies this process as a type of "corporate consent management" strategy, which is in line with what has been perceived throughout the interviews: the business strategy to act in the relationship with communities is, in fact, to consent to operate in the localities where they are installed.

Santiago and Demajorovic (2015, p.1) reinforce this perspective by stressing that "local communities emerge as key actors in governance arrangements in lieu of their proximity to extractive areas and the ability to affect the company's results."

Lyra et al. (2009) reinforce the importance of involving a wide range of potential stakeholders in this process, strengthening the relationship between the SLO process, stakeholder management, and the strategic nature of this process.

This orientation coincides with the concern of the interviewees, who clarify that, in addition to community, public authorities, Nonprofit Organization (NOs) and other stakeholders should be involved in the process, stressing that communities cannot be considered as "pure stakeholder", since, as part of the community, various stakeholders, such as those listed above, coexist. This Vision reinforces the direct relationship that exists between the company and the different social actors that coexist, impact and are impacted within their area of action and make up the "community".

Mayes (2015, p. 110) highlights other stakeholders to be considered in the SLO process: "[...] it is not only the expectations of communities that matter in gaining and maintaining SLO, but also in other groups, such as countries, organizations that support HR, and clients operating on a national and global scale. "

Santiago and Demajorovic (2014, p.2) summarize the theme by proposing that: “studies highlight the need for productive activities with great potential for impacts to receive an SLO” issued “by society, including government, NGOs, and communities”.

The interviews confirm this business perspective, given the existing demands from both reporting agencies and funding agencies, and the high costs of downtime or difficulties in the operation, as well as legal disputes. The interviewees also affirm the importance of the theme, especially for companies in the extractive sector due to the locational issue, fundamental in the exploration process.

In the interviews, the professionals indicate that there is not, in literature, a structured system or model for obtaining and maintaining the SLO, or practical approaches to its implementation. In the companies, community relationship management models have been used for this purpose.

The respondents are unable to indicate a specific and timely process for obtaining (and maintaining) the SLO. They understand that SLO is not justified as a means or process, but as a purpose and objective.

Professionals understand that the SLO becomes a more natural and not untimely process, because maintaining the relationship establishes certain levels of trust between the community and the company.

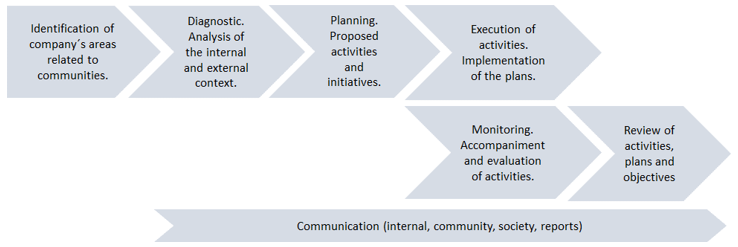

The identified community relationship management models vary among different types, but tend to maintain a common base, the PDCA (Plan-Do-Check-Act) cycle, or Stewart cycle. This appropriateness is also used by other reference organizations for the extractive segment, such as ARPEL and Accountability with some variations between the models, nomenclature, and quantity of steps proposed to carry out the process.

The choice for this cyclical model is justified by the dynamism of the contexts and the speed of change, since it favors the identification of the need for change and the correction of proposals and plans that do not obtain the expected results.

Santiago and Demajorovic (2014) establish three stages – for which they are called middle action – to obtain SLO and for other finalities: mapping, expectation, and engagement of stakeholders.

Such a model favors the constant and cyclical adequacy, identifying opportunities for improvement and acting in this direction.

Usually, the process of diagnosis or study of the communities precedes or is included in the planning, since the best knowledge about the scenarios is fundamental to the accomplishment of a good planning.

Interviewees also stressed the importance of identifying and carrying out a transversal work with all the areas involved in activities with communities, inserted in the figure as a "first stage". In parallel, the importance of different ways of communicating in the process was highlighted. Different publics should be prioritized, such as the internal public (different areas); the community (in the broad sense of the term); and reports to organizations for this purpose and to society in general.

From the different experiences and perceptions of the interviewees, the graphic representation proposed in Figure 2, below, was elaborated.

Figure 2. Model of community relationship management

Source: Researcher, 2018.

The article contributes to a field, clearly under construction, from the view of subjects involved with SLO-related practices. In addition to bringing the synthesis of the state of the art in relation to SLO for the text, it also brought the perspective of those who work with it in the practical field, problematizing the development of this field in the Brazilian context by companies in the mining industry.

The interviewees, when asked, did not recognized great references on the subject, citing few practices and guides (shown in Table 3) as benchmarking, in practice. However, the perception of the professionals regarding the theme was not far from the technical and scientific literature, as presented in Table 2. Nonetheless, the interviewees revealed perceptions that the literature does not present. These discoveries demonstrate the value of research for debate and a better understanding of the subject.

The literary revision on the theme allowed the perception of interdisciplinarity. This understanding was confirmed in interviews, where it is clear that even companies are still looking for a better organizational format for the development of this activity, which, in some cases, is fragmented in different areas. In practice, for interviews, this interdisciplinarity makes it difficult to carry out the process and sometimes generates multiple contacts, with different goals and means with the community, making communication difficult and creating bonds.

The interviewed professionals reported that the term is little used at the managerial level. There is fear of the process becoming formal, a new form of licensing. The managers most involved with the topic, say the interviewees, are precisely those who have had problems with their operations or, in other words, have lost their license to operate.

The professionals indicated that they understand SLO as a natural consequence of the effective and continuous relationship between company and community. The development of a cyclical process was indicated as the most appropriate, due to the dynamism of the relationship and the possibility of correcting the course of planned actions, based on the changes in the scenarios.

The professionals, incidentally, agree with the bibliography visited when pointing SLO as an activity directly related to community relations, emphasizing, however, the importance of the professionals involved in this process. In particular, they emphasize the important role of the professionals who work in the field, together with the community and the differentiated profile necessary to perform this function.

In reality, these professionals are considered fundamental to overcome the difficulties in operationalizing the SLO processes, a factor also highlighted by the interviewed professionals.

The importance of the SLO, presented in the Literary Review, was confirmed by the interviewees, especially for extractivist companies, but also for any major undertaking.

One of the conclusions of the research is the existence of a vast field of knowledge and theories to explore. Scientific literature is restricted and existing gaps allow researchers to roam through different possibilities.

This Research intends to fill some of these gaps by bringing the perception of professionals who live the routine of extractive companies in the search for the license to install and operate. In addition to the two products presented (conceptual analysis of terms related to SLO and basic model of community relationship), it contributes to the direction of new research and development of practical strategies related to SLO, mainly regarding the need to understand the culture, the local conditions, and the difficulty that the variety of this existence imposes for the elaboration of SLO implementation and follow-up strategies.

However, the research presents limitations that deserve to be recorded as the deepening of only one of the parts of the community relationship, the corporate vision, to the detriment of the community perspective and other stakeholders involved. It is Understood that this is a field to be explored.

Abdala, F. (2016), “Collaborative governance for sustainability: a multi-stakeholder approach to drive land use, conservation and social agenda in mining areas”, In: 24th World Mining Congress Proceedings, Rio de Janeiro, pp. 101-107.

Asociación Regional de Empresas del Sector Petróleo, Gas y Biocombustibles en Latinoamérica y el Caribe – ARPEL (2016), Sistema de Gestión de la Responsabilidad Social Corporativa, Marco de Referencia, ARPEL, Montevideo, Uruguay.

Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas – ABNT (2010), ABNT NBR ISO 26000 - Diretrizes sobre Responsabilidade Social, ABNT, Rio de Janeiro.

Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas – ABNT (2012), ABNT NBR 16001 – Responsabilidade Social – Sistema de Gestão – Requisitos, ABNT, Rio de Janeiro.

Bebbington, C. and Wilson, E. (2018), “Community Liaison Officers: On the Frontline of Social Risk Management”, SPE International Conference and Exhibition on Health, Safety, Security, Environment, and Social Responsibility, 16-18 April, Abu Dhabi, UAE, Society of Petroleum Engineers. doi: 10.2118/190682-MS

Boutilier, R. G. et al. (2012), “From Metaphor to Management Tool: How the Social License to Operate Can Stabilize the Socio-Political Environment for Business”, International Mine Management 2012 Proceedings, Melbourne, Australian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, 2012, pp. 227-237.

Bowen, F. et al. (2010), “When Suits Meet Roots: The Antecedents and Consequences of Community Engagement Strategy”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 95, No. 2, pp. 297-318.

Business for Social Responsibility – BSR (2016), The Future of Stakeholder Engagement - Transformative Engagement for Inclusive Business, Research Report. Business Leadership for an Inclusive Economy, 2016.

Campbell, G. and Roberts, M. (2010), “Permitting a new mine: insights from the community debate”, Resources Policy, September, Vol. 35, No. 3, pp. 210–217.

Davis. R. and Franks. D. M. (2014), Costs of Company-Community Conflict in the extractive Sector, Report, Harvard Kennedy School – Corporative Social Responsibility Initiative, Cambridge, MA.

Falck, A. et al. (2014), ”Selection of social demand-based indicators: EO-based indicators for mining”, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 84, pp. 193-203.

Faria, M. C. S. et al. (2018), “Licença Social para Operar: uma Perspectiva Teórica”, In XIV Congresso Nacional de Excelência em Gestão & IV INOVARSE CNEG, Rio de Janeiro, RJ.

Garnet, S. T. et al. (2018), “Social License as an Emergent Property of Political Interactions: Response to Kendal and Ford 2017”, Conservation Biology, Vol. 32, No. 3, pp. 734-736.

Gaviria, E. M. (2015), “A “Licença Social para Operar” na Indústria da Mineração: uma Aproximação a suas apropriações e sentidos”, Revista Brasileira de Estudos Urbanos e Regionais, Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 138-154.

Howard-Grenville, J. et al. (2008), “Constructing the license to operate: internal factors and their influence on corporate environmental decisions’, Law and Policy, Vol. 30, No. 1, pp.73–107.

Instituto Brasileiro de Mineração – IBRAM (2014), A Industria da Mineração para o desenvolvimento do Brasil e a promoção da qualidade de vida do brasileiro, IBRAM, Brasília, DF, available at: http://www.ibram.org.br/sites/1300/1382/00005649.pdf (access: Mar 22 mar, 2019).

Lyra, M. G. et al. (2009), “O papel dos stakeholders na sustentabilidade da empresa: contribuições para construção de um modelo de análise”, Revista de Administração Contemporânea, Vol. 13, Ed. Esp., Art. 3, pp. 39-52.

Maggiolini, P. and Nanini, K. (2010), “Corporate Social Responsibility as a Symptom of the Existential Dissatisfaction in Post-Industrial Economy”, Brazilian Journal of Operations & Productions Management, Vol. 3, No.1, pp. 49-69.

Marques, V. L. et al. (2018), “Tools for the strategic management of stakeholders in civil construction”, Brazilian Journal of Operations & Productions Management, Vol. 15, No. 4, pp. 595-609.

Mayes, R. (2015), “A Social Licence to Operate: Corporate Social Responsibility, Local Communities and the constitution of Global Production Networks”, Global Networks, Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 109-128.

Mcmahon, G. and Nemy, F. (2001), Large mines and the community: Socioeconomic and environmental effects in Latin America, Canada, and Spain, The Word Bank.

Oliveira, F. R. et al. (2015), “INOVARSE: Compartilhando Experiências e Desafios da Responsabilidade Social”, In Quelhas, O. L. G. et al. (Orgs.), Responsabilidade Social Organizacional: Modelos, experiências e inovações, Benício Biz, Rio de Janeiro, pp. 8-15.

Owen, J. R. and Kemp, D. (2013), “Social licence and mining: a critical perspective”, Resources Policy, Vol. 38, No. 1, pp. 29–35.

Pardini, D. J. et al. (2007), “Origens e Evolução da Responsabilidade Social Corporativa: uma Perspectiva Histórica de Quatro Siderúrgicas Brasileiras”, Revista de Administração FACES Journal, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 45-54.

Prno, J. and Slocombe, D. S. (2012), “Exploring the origins of ‘social license to operate’ in the mining sector: Perspectives from governance and sustainability theories”, Resources Policy, Journal Homepage, Vol. 37, pp. 346–357

Ruggie, J. G. (2014), Quando Negócios Não São Apenas Negócios, Planeta Sustentável, São Paulo.

Santiago, A., L., F. and Demajorovic, J. (2014), “Licença Social para Operar: Um Estudo de Caso a Partir de Uma Industria Brasileira de Mineração”, In XVI ENGEMA - Encontro Internacional sobre Gestão Empresarial e Meio Ambiente, São Paulo, 01-03 dez. 2014.

Santiago, A., L., F. and Demajorovic, J. (2015), “Relacionamento da Empresa com a Comunidade Local: Licença Social para Operar no Setor da Mineração”, In Quelhas, O. L. G. et al. (Orgs.), Responsabilidade Social Organizacional: Modelos, experiências e inovações, Benício Biz, Rio de Janeiro, pp. 260-279.

Sauerbronn, F. F. (2011), “Stakeholder Strategizing: uma Proposta de Investigação de Práticas de Responsabilidade Social e Relacionamento Comunitário”, Revista do Mestrado em Administração e Desenvolvimento Empresarial da Universidade Estácio de Sá, No. 1, pp. 38-55.

Soares, E. B. S. et al. (2011), “Análise de Dados Qualitativos: Intersecções e Diferenças em Pesquisa Sobre Administração Pública”, In III Encontro de Ensino e Pesquisa em Administração e Contabilidade - EnPEQ 2011, João Pessoa, PB, 20-22 nov. 2011.

Solomon, F. et al. (2008), “Social dimensions of mining: research, policy and practice challenges for the minerals industry in Australia”, Resources Policy, Vol. 33, pp. 142–149

Thomson, I. and Boutilier, R. (2011), The Social Licence to Operate. SME Mining Engineering Handbook, Society for Mining, Metallurgy, and Exploration, Colorado.

Werneck, N. (2013), A articulação dos conceitos Licença Social, Capital Social e Valor Compartilhado como orientadores da prática social da empresa, Memória do I Seminário de Responsabilidade Social da Petrobras, Rio de Janeiro, pp. 107 a 114. World Bank and International Finance Corporation (2002), Large Mines and Local Communities: Forging Partnerships, Building Sustainability, Washington.

Received: 25 Jan 2019

Approved: 23 May 2019

DOI: 10.14488/BJOPM.2019.v16.n3.a8

How to cite: Faria, M. C. S.; Neto, J. V.; Quelhas, A. D. (2019), “Social license to operate – the perspective of professionals from Brazilian extractive companies”, Brazilian Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 448-461, available from: https://bjopm.emnuvens.com.br/bjopm/article/view/749 (access year month day).