Perceptual analysis of heterogeneous stakeholders on the impact of the Rio 2016 games in the territory of Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas

Leonardo P. O. A. Campos

feedbacker.br@gmail.com

Fernando Oliveira de Araujo

Raynne Suzano de Freitas

Chrystyane Gerth Silveira Abreu

ABSTRACT

Highlights: Development of partnership with local entities for integrated social actions; Actions and projects are developed as close as possible to the public audience; Participation in meetings and community councils; Establishment of constant dialog between social management and community leaders; Dialog with public entities; Work communication with all the impacts caused by the implementation of the megaproject, according to the affected area.

Goal: Analyze, through a case study, what were the effects resulting from the Rio 2016 Olympic Games in the territory of Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas, and how they were perceived by the stakeholders during and after the performance.

Design / Methodology / Approach: On-site open and participant observation, semi-structured interviews, and on-site questionnaires and descriptive statistics

Results: A series of consequences were triggered, affecting each of the different stakeholders in different ways.

Limitations of the investigation: Megaprojects promote mutually positive and negative impacts concerning the local stakeholders and their multiple and different perceptions. Thus, results cannot be generalized. Practical implications: Fragmentation of the megaproject, heterogeneity, and perceptions of different stakeholders

Originality / Value: Practices that are sensitive to the stakeholders’ engagement and impacts perceived.

Keywords: Mega-events; Stakeholder Management; Olympic Games; Rio 2016.

1 INTRODUCTION

Mega-events, such as the World Cup and the Olympic Games, are unique initiatives that may leave permanent marks on society (Flyvbjerg et al., 2016; Müller, 2014; Zimbalist, 2015). As Müller (2015) asserts, the mega-event, in addition to attracting thousands of visitors and having a worldwide reach, requires significant investments in infrastructure, which generate impacts on the built environment and the local community.

Mega-events are closely related to big infrastructure projects, named megaprojects, which aim at urban reformulation. According to Flyvbjerg (2014), megaprojects are complex undertakings that cost in the range of billions of dollars, require many years to develop and execute, involves multiple stakeholders, and are transformational, as they affect millions of people.

In this sense, according to Oliveira (2011), mega-events and megaprojects may be perceived as propellers of a deliberate economic and social growth strategy, as they share some common elements: a) investment attraction; b) leverage of tourism; c) urban infrastructure; and d) an actuation of public-private partnerships (PPP).

For Zeng et al. (2015), megaprojects, such as the Olympic Games, can contribute to a strategic repositioning at the national level, in addition to social development. In this sense, the challenges to manage a mega-event are not purely technical; they also entail how to structure a context that encompasses and dialogues with the various stakeholders, who perceive the initiative under different social cultural views.

Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas is an important tourist attraction and is a free entertainment site in the city. It has an intense movement of residents, traders and passersby (Enrich-Prast, 2012), besides being a relevant logistic hub, since it interconnects different districts of the most noble area of the city (Humaitá, Jardim Botânico, Gávea, Leblon, Ipanema, and Copacabana), featuring a heterogeneous local community of individuals with different cultures, educational level, and social positions.

In the face of the relevance that Lagoa has to the context of Rio de Janeiro, the use of the territory of Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas is highlighted in the Rio 2016 Olympic Games, as the arena for some competitions and hosting some thematic houses of the delegations.

Lagoa was fragmented into dichotomous areas, in which the individuals were affected in different ways, thus making it possible for the rise of different views regarding the mega-event. Therefore, what were the effects arising from the mega-event Rio 2016 Olympic Games in the territory of Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas? And how were they seen by the different stakeholders during and after the Games?

Observing the context and considering the aforementioned question to be answered, the following objectives were the focus of investigation of this paper: (a) identify the practices of stakeholder management applied in the Rio 2016 Olympic Games, concerning the territory of Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas: (b) identify what the views on the mega-event among the various stakeholders were – formal and informal establishments, fishing community, passersby and tourists – while hosting the Rio 2016 Games; (c) check if there are different views among the stakeholders of the megaproject; (d) identify the consequences generated by the Rio 2016 Games in the Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas and evaluate whether these consequences relate to the possible practices of stakeholder management used; and (e) consolidate lessons learnt, aiming at sharing teachings of a success case in mega-events.

In this sense, to go deep into an analysis on the local stakeholder management, a better understanding about the territory where the Rio 2016 Olympic Games occurred was necessary, segmenting the analysis by micro-regions. According to Clark et al. (2016), this application of prioritizing the macro in relation to the micro in big projects and not properly considering the heterogeneity of the territory and its stakeholders may reduce the capacity to generate benefits to the local community, and even adversely affect a possible legacy.

Intending to meet the proposed goals, beyond the introduction, this study is subdivided as follows: section 2 provides a comprehensive literature review on stakeholder and megaproject management, encompassing the bases ISI Web of Science, Scopus, and Scielo. Section 3 contemplates the adopted study methodology. Section 4 describes and discusses the results arising from the field research with passersby and enterprises (formal and informal ones) within the territory of Lagoa. Section 5 summarizes the main lessons learnt with the analyzed situation and the sixth and last section provides the main conclusions of the research.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Mega-events

Hosting a mega-event, according to Horne and Whannel (2016), may be understood as one of the most relevant political initiative of the modern era, as they promote transforming effects on the population and place. Thus, according to Flyvbjerg et al. (2016), Randeree (2014), Müller (2015), Molloy and Chetty (2015), Müller (2014), Gezici and Er (2014) and Jennings (2013), mega-events can be exemplified as expositions, political summits, conventions, festivals, Summer and Winter Olympic Games, FIFA World Cup, Rugby World Cup, Formula 1, and Super Bowl.

To Müller (2015), on the one hand, there is the tourist attractiveness and the immediate reach that all mega-events provide, and on the other, there are the costs of hosting and facilitating a mega-event that may go up to millions, if not billions, of dollars. According to Randeree (2014), the high costs of big-sized events are related to the necessary infrastructure to host the event, such as transportation, telecommunication, electrical infrastructure availability, and accommodation, but with the direct costs of organizing the show itself, such as wages of the involved professionals, safety or arenas for carrying out the competitions. To Fourie and Santana-Gallego (2011), mega-events can produce tangible benefits: infrastructure and economical return; and intangible benefits, which are hard to be measured: national pride, patriotism, and visibility of the hosting place.

Before the possible impacts generated by the big-sized event, according to Randeree (2014), the management of mega-events must include participatory strategic actions, that is, they must provide a context that is able to stimulate participation and collaboration between the different and heterogeneous stakeholders.

Regarding this, according to Clark et al. (2016), the mega-event has the ability to reshape the physical space, reconfiguring social relationships and influencing the way in which the local population and the place are understood.

Management of stakeholders

According to Mok et al. (2015), the complex and uncertain character of megaprojects requires an effective stakeholder management, in order to support the multiple interests of the stakeholders and avoid conflicts. To Al Nahyan et al. (2012), the stakeholders have multiple interests and multiple roles, with all of them gathered in a big group that belongs to the megaproject. In this context, it is important to consider that these stakeholders may have a macro common interest; however, they may not necessarily share a common goal.

According to Mazur and Pisarski (2015), stakeholder management concerns a process that involves a series of stages: identify the stakeholders; define a management model capable of promoting interaction with the stakeholders and categorize them for defining the strategies; engage and create engagement with the stakeholders; and maintain the relationship for the project feasibility. In turn, to Mok et al. (2015), stakeholder management must be contemplated under four perspectives: (1) interests and influences of the stakeholders; (2) stakeholder management during the process; (3) methods for analysis of the stakeholders; and (4) engagement of the stakeholders.

Thus, according to Freitas (2016); Guo et al. (2014); Jia et al. (2011); Jordhus-Lier (2015); Kytle and Ruggie (2005); Liu et al. (2016); Mok et al. (2015); Sami (2013); Shi et al. (2015); Teo and Loosemore (2010), the main practices regarding stakeholder management were defined: [1] mapping of the local population’s social profile; [2] division of the population according to its social profile; [3] preparation of actions based on the social profile and demands; [4] development of partnerships with local entities for integrated social actions; [5] communication with the local stakeholders is done strictly through social management; [6] actions and projects are developed as close as possible to the target public; [7] participation in meetings and community councils; [8] establishment of constant dialog between the social management and community leaders; [9] construction works in critical places, under the perspective of social instability and violence, are followed by the community mediator; [10] channel of direct communication between the community and the organization; [11] promotion of access to culture, leisure, and entertainment; [12] dialog with public entities; [13] assuring measures; [14] construction communication with all the impacts caused by the implementation of the megaproject according to the affected area; [15] committee for crisis management; and [16] social mobilization before the construction operationalization.

The non-engagement of the stakeholders in the megaproject management, according to Clark et al. (2016), can be considered a risk factor to the execution of the project, as it interferes in the delivery of results, thus minimizing and/or suppressing the benefits that can be generated. Therefore, Mok et al. (2015) assert that it is necessary to develop management tools that can promote collaboration with the stakeholders; carry out social learning; facilitate sharing the project goals and information; and provide ethical processes to maintain equity. Thus, according to Zhai et al. (2009), the values or benefits of a large-scale project may feature multiple dimensions; however, these dimensions must be coordinated by different demands of heterogeneous stakeholders that encompass the megaproject.

3 METHODOLOGY

For the beginning of this research, the Rio 2016 Olympic Games mega-event was selected. In empiric terms, the case of one of the global benchmark mega-events, according to Clark et al. (2016), is explored: the Olympic Games, through the study of potentialities and practical limitations of megaproject management. The Rio 2016 Games, held in the city of Rio de Janeiro, capital of the State that has the same name, and being the first edition of the Olympics and Paralympics in South America, represented a possibility of transformation in the society, affecting the life of millions of individuals.

The city of Rio de Janeiro can be considered the second most important capital in Brazil, with the first being the city of São Paulo. According to IBGE – Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (2016), the city of Rio de Janeiro featured in 2016, the last measurement, a population of 6,498,837 inhabitants, territorial unit of 1,200,177 km² and demographic density of 5,265.82 (inhabitants/km²). Regarding economic data, according to a measurement carried out in 2014, the municipality features the second largest GDP – Gross Domestic Product of the country, only below the city of São Paulo.

The host city, which was once the capital of Brazil, from 1763 to 1960, needed to go through a set of transformations that could facilitate holding the Olympics. It is important to highlight, according to Osório and Versiani (2013), that the transfer of the capital to Brasília in 1960 triggered a fracture in the institutional pace of the city of Rio de Janeiro, complicating the consistent organization of regional strategies and policies, which may be seen to this day.

Rio de Janeiro stands out by its social confrontation, mount x asphalt asymmetry, and its cultural diversity. As Corrêa (2006) asserts, during the latest decades, the favela was assumed as a space apart from the city with its own laws and codes. Moreover, poverty mixes with violence: the favela turned into a territory ruled by crime. Corrêa (2006) also points out the peculiarity of the way of life of these communities, which contrast with the life standard of the high social classes and with habits of the urbanized city. It is worth highlighting that many favelas are located in noble areas and neighborhoods of the city or very close, showing, according to Leite (2014), a fine line of the special, social and moral borders between these spaces and their residents.

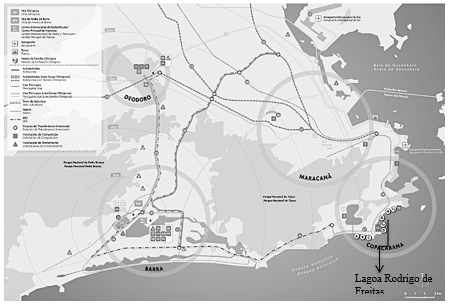

It is in this heterogeneous and multicultural space that the Rio 2016 Olympic Games (the object of this study) were held in different geographic locations of the host city, from August 5th to 21st, and the Paralympics were held from September 7th to 21st. The Olympics, according to the Rio 2016 official website (2016), involved 42 sports, 306 events, 37 arenas, and competitors from 205 countries. Despite all the structure of this event spread throughout the micro-region of Rio de Janeiro, some neighborhoods stood out, concentrating the competitions, according to Figure 01: Deodoro, Copacabana, Barra da Tijuca, Maracanã, and Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas.

Figure 1. Map of venues of the Rio 2016 Games

Source: Meirelles (2014, p. 58).

Each micro-region features a high number of actors that form a local community that was affected by the Olympics. Fragmenting the megaproject into smaller areas may enable a more consolidated analysis on the object of study.

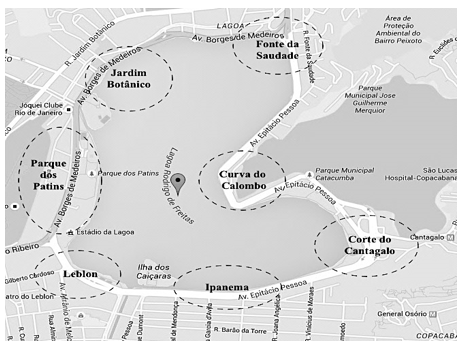

Therefore, the neighborhood selected for study purpose was Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas, which was segmented by the authors, and backed by studies of Clark et al. (2016), into seven micro-regions: Fonte da Saudade, Curva do Calombo, Corte do Cantagalo, Lado de Ipanema, Lado do Leblon, Lado do Jardim Botânico, and Lado Jardim Botânico/Parque dos Patins, according to Figure 02.

Figure 2. Fragmentation of Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas into micro-regions

Source: adapted from Google Maps (2016).

To receive the rowing and sprint canoe competitions, Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas, underwent necessary transformations, in its water mirror and surroundings, such as the fencing and construction of the bleachers for the Rowing Arena, in order to facilitate the games.

The fencing at Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas for holding the Olympic Games modified the landscape and the daily routine of the local individuals and local enterprises. It is worth highlighting, according to SESGE - Secretaria Extraordinária de Segurança para Grandes Eventos (Extraordinary Secretary of Security for Major Events), that the fences were deployed as a safety measure demanded by the Rio 2016 organizing committee to generate protection, as reported in Folha de São Paulo’s website (2016). However, the understanding about this fencing triggered different perceptions among the local enterprises, fishing community, rowing clubs, and passersby.

The following method was applied: [1.] open and participant observation, in order to carry out a more intense on-site interaction with the social context; [2.] semi-structured interviews and on-site questionnaires, to collect primary data that open and participant observation alone would not be able to provide; and [3.] descriptive statistics.

It is worth pointing out that 22 passersby (among residents, tourists, and habitual sport players in the region) were randomly interviewed and 45 formal and informal enterprises or associations, with the purpose of answering the referred questions: (A) What were the main impacts (should they be positive and/or negative) noticed by the stakeholders? (B) What were the practices of stakeholder management adopted? And did they consider the heterogeneity of publics that constitute the different territories? And (C) did the mega-event leave a legacy for the local community of Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas?

Case of the Rio 2016 Olympic Games

Analysis and discussions of the passersby’s perceptions

The Olympic Games modified the daily life of the city of Rio de Janeiro, with impacts also on the region of Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas. Regarding the 22 interviewees, 11 respondents signalized that they had been informed of the possible changes that would happen in Lagoa for holding the Olympic competitions. It is worth pointing out that, from these 11 respondents, nine used to visit Lagoa for more than 3 years, and they informed that they learned about the impacts through the following media: newspaper, Internet, the government's propagandas, and by word of mouth. Since 11 respondents declared that they did not know about the possible impacts, it is possible to question if the method of communication, used to sensitize and dialogue with the local stakeholders as the passersby of Lagoa, was effective or not.

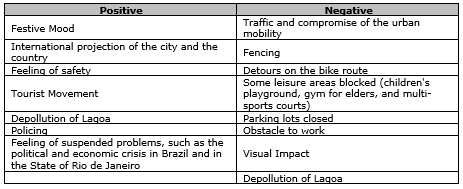

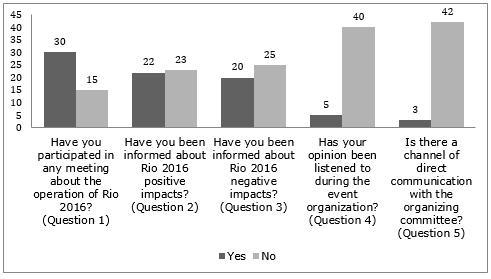

Also, on the impacts, the 22 respondents informed what were the effects they had undergone in their daily life in using Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas as a stage for Olympic competitions, as systematized in Table 01:

Table 1. Main positive and negative changes in the daily life of the respondents

Source: authors (2016)

Also about Table 01, the most commented positive point by the sample, representing six interviewees, was the feeling of safety in Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas and the ostensible policing, while holding the event. Nevertheless, the “fencing” was the most highlighted negative aspect among the passersby, representing seven respondents. It is worth pointing out that the fencing is also one of the reasons of restriction for some leisure areas in Lagoa, leaving those parts deserted, without the movement of people.

It worth highlighting that the depollution of Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas is featured as a simultaneously positive and negative aspect, as a part of the respondents understood that it was an initial process to make the lagoon cleaner, generating some benefit. The other part understood that it was a frustrated attempt, because it entailed waste of resources and visual impact, since big machinery was inside the lagoon.

The interviewees were also asked if there was a perception of benefits associated with the posting of Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas as the stage of activities of the Rio 2016 Games. Seventeen respondents reported that they were happy about holding the Rio 2016 Games in Lagoa, because, in addition to the established euphoric mood, they stated that it was a possibility to make the location known by the rest of the world. Moreover, from these 17 interviewees, 15 respondents were satisfied with the organization carried out for the Rio 2016 Games in Lagoa. However, 15 interviewees also reported that they disagreed or could not see the benefits generated by holding the games in Lagoa.

Nevertheless, 16 respondents informed that there would be a tangible legacy: the infrastructure – transportation, the Olympic boulevard, and the Olympic parks; and intangible: global exposure of Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas and the city of Rio de Janeiro.

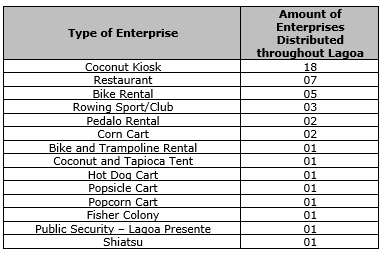

Analysis and discussions of the perceptions of Enterprises

Regarding the type of establishments throughout Lagoa, the Coconut Kiosks were the most recurring establishments found, a total of 18 enterprises, according to Table 03, and they are distributed all over Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas. These formal enterprises, registered with the Administration of the City of Rio de Janeiro, have up to three employees and, generally, they are a family business, managed by a couple or parents and children. From the 18 Coconut Kiosks, 16 are installed in Lagoa for over 10 years.

Table 2. Distribution of the enterprises regarding the type of enterprise

Source: authors (2016)

From the 45 interviewed establishments, six enterprises are also in the food segment, and they are distributed in popsicle, tapioca, corn, and hot dog carts. These establishments follow the characteristics of Coconut Kiosks: up to three employees, family management, and have been running in Lagoa for some years. However, there is a particularity: from the six businesses, two are informal, and one was in the process of becoming formal by the city administration.

There was a balance regarding the positive and negative perceptions concerning the mega-event. It is worth highlighting that the 21 respondents, from the sample of 45, declared that the Olympic Games positively affected the daily life of Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas. Some of the main aspects mentioned as positive by the 21 respondents are policing, more people movement in Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas, and raise in sales.

It is worth pointing out that the business owners did not see the sales as the main positive factor, as most of the establishments did not have significant raises. However, according to the manager of one of the interviewed restaurants, the movement and sales rose dramatically, being one of the best since the business foundation, located in Corte do Cantagalo, beside the temporary establishment House of Switzerland, a hosting house of the Swiss government that operated during the Olympics and Paralympics, providing visitors with entertainment.

Although also mentioned as a negative factor by one respondent, the House of Switzerland was seen as a positive action. Also known as Baixo Suíça, this undertaking attracted thousands of people, having queues with waiting time of approximately one hour and thirty minutes. Given the success of this undertaking, it polarized a significant rise of people circulating through the subarea of Corte do Cantagalo and enjoying the nearby establishments.

In contrast to the positive perception, 20 interviewees informed that the mega-event produced negative impacts. From the reasons of negative impacts caused to Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas, the main effect mentioned is the fencing that happened in some parts of Lagoa, thus triggering a set of damages: (a) unfeasibility to use the parking lot of Parque dos Patins; (b) it reduced people movement, therefore, reducing sales; (c) some establishments became unable to operate; (d) other enterprises had to be moved from their original place to continue operating; (e) some areas became virtually deserted, with no movement of people. It is worth mentioning that the main areas affected by the fencing were Fonte da Saudade, Parque dos Patins and Leblon part, more precisely around Clube de Regatas do Flamengo.

Several establishments underwent negative impacts due to the Rio 2016 Games. However, it is worth highlighting the case of the fisher colony – Z13. Due to the fencing, the colony was completely fenced, remaining isolated. The fishers, after a lot of negotiation with the games organizing committee, managed to have access to the colony and to Lagoa to fish only during the time between 8 pm and 5 am. However, this action was not enough, because the fishers could not park the trucks next to the colony to take the fish and store them in ice.

Many fishers, due to living far or even in other municipalities, decided to suspend their activities, staying away from the colony, without fishing for up to three months. At first, the fishers informed that the organizing committee of the Rio 2016 Olympic Games had presented a contingency plan, in which the fishers would be reassigned to activities of Rio 2016, intended for them to have an extra income until they would fish again. Nevertheless, this initiative was not implemented and, consequently, some fishers underwent financial problems. It is worth pointing out, according to the fishers themselves, that there was no counterpart by the organizing committee in order to mitigate this specific issue.

Regarding the four interviewees that showed indifference to the perception of the consequences resulting from the mega-event, they did not take a position about the existence of positive or negative effects. To these respondents, the number of people circulating in Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas had a considerable raise, but it did not influence the number of sales, keeping the service normal. These interviewees highlight that any positive or negative effect would be temporary at the location. Although many enterprises noticed the negative consequences resulting from the operation of the Rio 2016 Olympic Games, some establishments considered these aspects as necessary for the performance of the competitions.

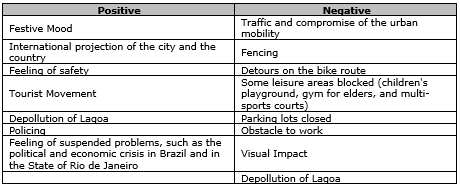

In face of the negative, positive or neutral perceptions, five questions were proposed to check the community’s level of interaction with the organizing committee of the Rio 2016 Olympic Games, as illustrated in Figure 03:

Figure 3. Distribution of the questions on the relation between the organization of the Olympic Games and the local community

Source: authors (2016)

Thirty respondents informed that they participated in at least two meetings about holding the mega-event in Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas. Complementing question 01, the questions 02 and 03 were asked and analyzed, as it was intended to understand whether there was transparency in communicating the possible consequences, both beneficial and prejudicial, resulting from holding the Rio 2016 Games to the enterprises.

Regarding the positive effects, the respondents themselves commented that they were informed about the great amount of tourists circulating in Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas, raise in sales, and the ostensible policing. In turn, regarding the negative impacts (question 03), from the 45 interviewees, only 20 respondents said that they knew about the fencing and its developments: parking lot of Parque dos Patins academia, third age gym in the Leblon part unusable, children's playground in Fonte da Saudade isolated without access, visual impact of the grids around the lagoon itself, and visual obstruction to watch the Olympic rowing competitions in some parts of Lagoa. According to the respondents, the Olympic Committee informed about the fencing, but not about how this process would be.

Thus, questions 02 and 03 reveal that there were mistakes in the communication process of the mega-event managers with the stakeholders of Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas. In turn, the answers obtained regarding question 04 suggest that there were failures in the practices of stakeholder management of the mega-event, as 40 respondents informed that their opinion was never contemplated in the planning of the organization of the Olympic Games.

The answers obtained for question 05 suggest an opportunity of improvement in the communication process of the mega-event, as well as an ineffective practice of stakeholder management, without a channel of direct communication with the organizing committee, which could be represented by an individual or a group that could assist the enterprises.

Although there is evidence of mistakes in the management of stakeholders and negative impacts resulting from the mega-event, 34 of the interviewees claimed to be happy about holding the Rio 2016 Olympic Games in Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas.

Comparative analysis among the passersby and enterprises

The analysis of the perceptions of the enterprises involved more variables than the one of passersby. Nevertheless, both enterprises and passersby mentioned the same positive and negative consequences that concurrently affected both, as systematized in Table 04:

Table 3. Main positive and negative consequences common to the daily routine of enterprises and passersby

Source: authors (2016)

The fencing was mentioned by both profiles as the main negative impact caused by the Rio 2016 Olympic Games, as it triggered a set of other impacts. It is worth pointing out that, according to the interviewees, as to enterprises, Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas was fragmented into areas of greater movement, Corte do Cantagalo and areas with a smaller concentration of people, and Parque dos Patins.

As for the positive consequences, some were ephemeral, such as the festive mood promoted by the mega-event; however, some were permanent, such as the infrastructure created for holding the Games. The ostensible policing and the tourism movement in Lagoa were the beneficial aspects most commented by the respondents, both passersby and enterprises.

Contrasting the empiric results with the literature

According to the studies carried out, it is possible to see a complementarity between the data collected through the literature review and the data acquired through the empiric research.

As demonstrated in the literature review, according to Hu et al. (2015), Mazur et al. (2015), Chang et al., (2013), Zhai et al. (2009), a megaproject, in this case, portrayed by mega-event Rio 2016 Olympic Games, has the following characteristics: (a) budget above 500 million dollars; (b) high level of complexity, uncertainty, ambiguity, and dynamic interfaces; (c) involvement of technology and long periods of execution; (d) high attraction of public and political interest; and/or (e) defined more by effects than by solutions.

In this sense, in the analysis carried out in the territory of Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas, it was possible to verify and witness the following characteristics: (1) high level of complexity, uncertainties, ambiguity, and dynamic interfaces, since several different perceptions were presented by the interviewed stakeholders; (2) attraction of public and political interest, however, in a deficient way, as many interviewees felt hampered by the Olympic performance; and (3) more effects than solutions, such as failure to meet one of the promises: depollution of the lagoon (solution); in contrast, there was the exposure of Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas to Brazil and the world (effect).

According to Müller (2015), sports mega-events on the one hand provide a tourism attractiveness and an immediate achievement, and on the other, the cost of hosting and facilitating the Olympics, which may go up to hundreds of millions, if not billions of dollars. These understandings were verified through the interviews, especially, in the case of passersby, as many informed the tourist movement in Lagoa and in the city as a positive aspect, but they questioned the high expenses for the Olympic Games, and said that these expenses could have been applied to other more relevant areas, such as healthcare and education.

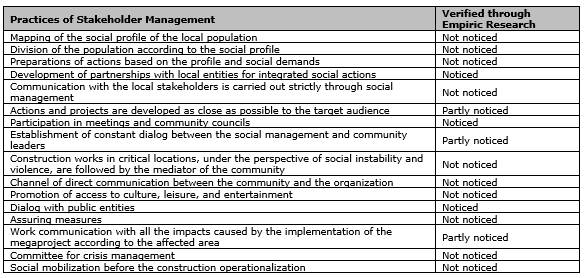

According to Grabher and Thiel (2015), the organization and planning of a mega-event, such as the Olympic Games, involve several specialized organizations in the execution, which are put in charge for ensuring the costs of the megaproject, complete the infrastructures, negotiate with several stakeholders and manage the event day-by-day. In this sense, and based on Table 04, efforts were made to analyze which practices of stakeholder management were contemplated in the management of the Rio 2016 Olympics, concerning the geographic space of Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas.

Table 4. Practice of stakeholder management noticed on the stakeholders of Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas

Source: adapted from Freitas (2016).

Effective stakeholder management, according to Chang et al. (2013), has dynamic communication and relationship management as key strategies to achieve a successful mega-event. In turn, to Zhai et al. (2009), the values or benefits of a large-scale project may have several dimensions; however, these dimensions must be coordinated by the different demands of heterogeneous stakeholders that encompass the megaproject, portrayed by the Rio 2016 Olympic Games.

According to Chang et al. (2013) and Zhai et al. (2009), the benefits of big-sized projects may have explicit roles: the infrastructures and events that they provide; the cognitive and the emotional experience that they produce. However, these explicit and implied benefits caused different concurrent perceptions on the stakeholders located in Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas. Although the interviewees presented a feeling of euphoria due to the performance of the Olympic Games, some questioned whether there would be any benefit for Lagoa after the end of the event.

According to Müller (2015), four dimensions must be considered with regard to receiving a mega-event in a particular location: capacity to attract visitors; immediate achievement; cost; and transforming impacts. Therefore, by further elaborating this understanding, it is possible to see that Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas contemplated these four dimensions: attracting many tourists, promoting a festive mood throughout the region, having investments as the subway station in Corte do Cantagalo and modifying the daily routine of individuals and enterprises both positively and negatively.

As highlighted by Clark et al. (2016), the macro is prioritized in relation to the micro in several megaprojects, what may entail a defective analysis of the heterogeneity of the territories and their stakeholders, reducing the capacity to generate benefits for the community, even adversely affecting a possible legacy. This effect is properly noticed in the Rio 2016 Olympic Games, regarding Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas.

Thus, the confrontation of the primary and secondary data facilitates structuring a framework of necessary information to answer the problem-questions envisioned in this study.

4 CONCLUSION AND LIMITATIONS

This study presents a contribution regarding the analysis of local stakeholders in the management of megaprojects, especially concerning mega-events. Therefore, to carry out the analysis of the main object of this study, five specific objectives were constituted, presented in the introduction, and they were answered in the course of the research.

Thus, the first specific objective (SO) to be explained was the identification of the practice of stakeholder management. From the 16 practices that comprehend the management of megaprojects, the adoption of only six practices were identified in the management of the Olympics in Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas:

- Development of partnership with local entities for integrated social actions;

- Actions and projects are developed as close as possible to the public audience;

- Participation in meetings and community councils;

- Establishment of constant dialog between social management and community leaders;

- Dialog with public entities;

- Work communication with all the impacts caused by the implementation of the megaproject according to the affected area.

It is worth highlighting that the implementation of some practices was partially noticed, as shown in Table 05.

Through the practices applied and the practices that were not implemented in the management of stakeholders in the territory of Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas, it was possible to verify that a series of consequences were triggered, affecting each of the different stakeholders in different ways - passersby, tourists, formal and informal establishments, fisher community, sports clubs, and security initiatives - involved in the mega-event, answering to the second SO.

This study reassert the relevance of analyzing the heterogeneity among local stakeholders, as the stakeholders may have multiple and different perceptions. One of the alternatives to carry out this analysis is to break up the macro diagnosis on a megaproject into micro cores, just as the region of Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas was fragmented. This division, which meets the third SO, confirmed and promoted the existence of different perceptions, the one positive and the other negative, on the performance of the event in the location of Lagoa, especially concerning the establishments.

According to the fourth SO, on the one hand, in the region of Parque dos Patins, the fencing of the lagoon and the parking lot caused the reduced number of clients in the establishments, and in some cases, the closing of the enterprise during the Olympics, in order to minimize damages. It is worth highlighting that, during the Rio 2016 Games, many enterprises experienced their worst moment in terms of operation and sales since the business was opened in Lagoa. On the other hand, the establishments located in the region of Corte do Cantagalo saw a rise in the number of sales and the movement of tourists in that area. Some establishments commented that it was the best sale period in Lagoa.

Besides the enterprises, the passersby also showed a different perception. Despite mentioning negative impacts resulting from holding the games, it can be said that the passersby were taken by the euphoric and festive feeling that was established throughout the city, thus putting the negative effects in second place.

It is clear that the Rio 2016 Olympic Games produced different perceptions on the heterogeneous local stakeholders of Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas. These different perceptions may directly influence the possible benefits to be perceived, such as: the subway train and the infrastructure built in the region; the exposure of Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas as a piece of public leisure equipment and a tourist attraction; the structure of lanes on the water mirror of the lagoon for rowers of the nearby Clubs, in addition to the incentive to various water sports; and restoration of Colônia de Pescadores Z-13.

It is possible to notice that mega-events, which hold complexity and magnitude, are great producers of impacts at the location where they occur. However, they rarely cause benefits or damage only. In their majority, megaprojects promote mutually positive and negative impacts concerning the local stakeholders and their multiple and different perceptions.

A year after the ending of the Olympics of Rio de Janeiro and with the reduction of the euphoric mood, many questionings are found regarding the legacy left by Rio 2016 Olympic Games to the city and particularly to Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas. However, under an analysis of the national and international media on the presence of public at the competitions, the Rio 2016 Games were an unquestionable success.

In this sense, a sound analysis regarding the possible legacy that can be facilitated from mega-events to the host cities is necessary to understand in a more assertive way what are the short-term and long-term benefits that mega-events may offer to the host location. Therefore, a new empiric research on other mega-events is suggested, in order to confront the possible results and understand the real intention of receiving a project with this magnitude in a given city.

REFERENCES

Al Nahyan, M. T.; Sohal, A. S.; Fildes, B. N. et al. (2012), “Transportation infrastructure development in the UAE: stakeholder perspectives on management practice”, Construction Innovation, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 492-514.

Chang, A.; Hatcher, C.; Kim, J. (2013), “Temporal boundary objects in megaprojects: mapping the system with the integrated master schedule”, International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 31, No. 3, pp. 323–332.

Clark, J.; Kearns, A.; Cleland, C. (2016), “Spatial scale, time and process in mega-events: the complexity of host community perspectives on neighborhood change”, Cities, Vol. 53, pp. 87-97.

Corrêa, F. B. (2006), “As projeções de alteridade no espaço urbano carioca: a favela no cinema brasileiro contemporâneo”, Lumina, Facom/UFJF, Vol. 9, No. 1/2, pp. 51-61.

Enrich-Prast, A. (2012), “Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas: futuro”, Oecologia Australis, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 721-727.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2014), “What you should know about megaprojects and why: an overview”, Project Management Journal, Vol. 45, No. 2, pp. 6-19.

Flyvbjerg, B.; Stewart, A.; Budzier, A. (2016), The Oxford Olympics Study 2016: cost and cost overrun at the games, Said Business School, Working Paper 2016-20, University of Oxford.

Folha de São Paulo (2016), Trecho da Lagoa é cercado com grades de 2,5 metros para provas da Rio-2016, avalilable at: http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/esporte/olimpiada-no-rio/2016/07/1794794-trecho-da-lagoa-e-cercado-com-grades-de-25-metros-para-provas-da-rio-2016.shtml (access 30 July 2016).

Fourie, J.; Santana-Gallego, M. (2011), “The impact of mega-sport events on tourist arrivals”, Tourism Management, Vol. 32, No. 6, pp. 1364-1370.

Freitas, R. S. (2016), Riscos sociais em megaprojetos: uma confrontação da teoria com prática a partir do caso porto maravilha, Rio de Janeiro, Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade Federal Fluminense, Niterói, RJ.

Gezici, F.; Er, S. (2014), “What has been left after hosting the Formula 1 Grand Prix in Istanbul?”, Cities, Vol. 41, pp. 44-53.

Google Maps (2016), available at: https://www.google.com.br/maps/@-22.9715893,-43.2178451,15z (Access 4 Aug 2016).

Grabher, G.; Thiel, J. (2015), “Projects, people, professions: trajectories of learning through a mega-event (the London 2012 case)”, Geoforum, Vol. 65, pp. 328-337.

Guo, F.; Chang-Richards, Y.; Wilkinson, S. et al. (2014), “Effects of project governance structures on the management of risks in major infrastructure projects: A comparative analysis”, International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 32, No. 5, pp. 815-826.

Horne, J.; Whannel, G. (2016), Understanding the Olympics, 2. ed., Routledge.

Hu, Y.; Chan, A. P.; Le, Y. et al. (2015), “From construction megaproject management to complex project management: bibliographic analysis”, Journal of Management in Engineering, Vol. 31, No. 4.

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística – IBGE, available at: http://cidades.ibge.gov.br/xtras/perfil.php?lang=&codmun=330455&search=rio-de-janeiro|rio-de-janeiro|infograficos:-informacoes-completas (Access 22 Nov 2016).

Jennings, W. (2013), “Governing the Games: High Politics, Risk and Mega-Events”, Political Studies Review, Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 2-14.

Jia, G.; Yang, F.; Wang, G. et al. (2011), “A study of mega project from a perspective of social conflict theory”, International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 29, No. 7, pp. 817–827.

Jordhus-Lier, D. (2015), “Community resistance to megaprojects: the case of the N2 Gateway project in Joe Slovo informal settlement, Cape Town”, Habitat International, Vol. 45, pp. 169-176.

Kytle, B.; Ruggie, J. G. (2005), “Corporate social responsibility as risk management: a model for multinationals, Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative, Working Paper No. 10.

Leite, M. P. (2014), “Entre a ‘guerra’ e a ‘paz’: Unidades de Polícia Pacificadora e gestão dos territórios de favela no Rio de Janeiro”, Dilemas: Revista de Estudos de Conflito e Controle Social, Vol. 7, No. 4, pp. 625-642.

Liu, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, H. et al. (2016), “Handling social risks in government-driven mega project: An empirical case study from West China”, International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 34, No. 2, pp. 202-218.

Mazur, A. K.; Pisarski, A. (2015), “Major project managers' internal and external stakeholder relationships: The development and validation of measurement scales”, International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 33, No. 8, pp. 1680-1691.

Meirelles, E. N. (2014), El legado de grandes eventos esportivos en la producción de espacios urbanos sostenibles: perspectivas de Rio de Janeiro, Dissertação de Mestrado, Universitat Politecnica de Catalunya, Barcelona.

Mok, K. Y.; Shen, G. Q.; Yang, J. (2015), “Stakeholder management studies in mega construction projects: A review and future directions”, International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 33, No. 2, pp. 446-457.

Molloy, E.; Chetty, T. (2015), “The rocky road to legacy: Lessons from the 2010 FIFA World Cup South Africa stadium program”, Project Management Journal, Vol. 46, No. 3, pp. 88-107.

Müller, M. (2014), “After Sochi 2014: costs and impacts of Russia’s Olympic Games”, Eurasian Geography and Economics, Vol. 55, No. 6, pp. 628-655.

Müller, M. (2015), “The Mega-Event Syndrome: why so much goes wrong in mega-event planning and what to do about it”, Journal of the American Planning Association, Vol. 81, No. 1, pp. 6-17.

Oliveira, A. (2011), “A economia dos megaeventos: impactos setoriais e regionais”, Revista Paranaense de Desenvolvimento, No. 120, pp. 257-275.

Osorio, M.; Versiani, M. H. (2013), “O papel das instituições na trajetória econômico-social do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Cadernos do Desenvolvimento Fluminense, No. 2, pp. 188-210.

Randeree, K. (2014), “Reputation and mega-project management: lessons from host cities of the Olympic Games”, Change Management: An International Journal, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 1-7.

Rio 2016. (2016), Os Jogos em Números, available at: https://www.rio2016.com/olimpicos (Access 12 Aug 2016).

Sami, N. (2013), “From Farming to Development: Urban Coalitions in Pune, India: Urban development coalitions in Pune, India”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 151-164.

Shi, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zuo, J. et al. (2015), “On the management of social risks of hydraulic infrastructure projects in China: a case study”, International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 33, No. 3, pp. 483-496.

Teo, M. M. M.; Loosemore, M. (2010), “Community‐based protest against construction projects: The social determinants of protest movement continuity”, International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 216-235.

Zeng, S. X.; Ma, H. Y.; Lin, H. et al. (2015), “Social responsibility of major infrastructure projects in China”, International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 33, No. 3, pp. 537-548.

Zhai, L.; Xin, Y.; Cheng, C. (2009), “Understanding the value of project management from a stakeholder's perspective: Case study of mega‐project management”, Project Management Journal, Vol. 40, No. 1, pp. 99-109.

Zimbalist, A. (2015), Circus Maximus: the economic gamble behind hosting the Olympics and the World Cup, Brookings Institution Press, Washington, DC.

Received: 10 May 2018

Approved: 10 Aug 2018

DOI: 10.14488/BJOPM.2018.v15.n4.a11

How to cite: Campos, L.; Araujo, F.; Freitas, R. et al (2018), “Perceptual analysis of heterogeneous stakeholders on the impact of the Rio 2016 games in the territory of Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas”, Brazilian Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 15, No. 4, pp. 576-587, available from: https://bjopm.emnuvens.com.br/bjopm/article/view/577 (access year month day).