Premisses for a Public Policy to Foster the Creative Economy: the case of Ancine

Roberto Gonçalves Lima

National Cinema Agency – Ancine, Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

rogolima@hotmail.com

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this paper is to identify the premisses that have oriented the construction process of structuring public policies to the audiovisual domain draw on the ten years managerial experience of Brazil's National Cinema Agency (Ancine), also seeking to take a look at how such experience can bring perspectives to the formulation and management of policies directed towards the Creative Economy.

Keywords: Creative Economy; Brazil’s National Cinema Agency; Public Policy

1 INTRODUCTION

Upon the globalization of the economy and the technological convergence, the dissemination and consumption of cultural goods has become increasingly fast and easily produced and, in parallel, the detention of intellectual property rights is ever more concentrated.

In the beginning of the XXI century, in which communication has become the main economic activity of the planet, nations, companies, artists and institutions of all kinds and origins fiercely dispute every inch of the huge revenue generated by cultural contents.

For national economies, it is fundamental to find a place in this new ecosystem, and it is the public sector's attribution to foster national economic agents in order to aid them in reaching such place, and also to the shelter their insertion into the domestic market.

However, this globalization of communication leads to the creation of a greater number of spaces in which difference and diversity struggle for ethical, aesthetic, political and cultural resistance to face taste standardization, the concentration of revenues and rights and other kinds of behaviors that are harmful to the perception of identity and to the freedom of expression.

This implies that public authorities must also play a role in supporting and fostering cultural diversity with a view to affirm the specificity of interests and the history of the society that it belongs to.

Said dialectic lies on the origin of the complexity associated to public policies directed to the promotion of Culture in general, also falling upon the Creative Economy in particular: in Culture and Arts, under the capitalist mode of production, everything is simultaneously deemed as goods and rights, and not facing the complexity of this dialectic means that policies are doomed to failure and incompleteness.

A quick glance at the history of cultural policies in Brazil, mainly in the federal sphere, shows a tradition of emphasis on fostering the production of works to the detriment of other links of the productive chain, such as qualification, management, projects development, flow, public communication, promotion of audience, among other possible implications depending on the cultural segment that is taken as an example.

Another observable feature is the scarce or even non-existing concern on the detention of effective rights over the works of our cultural producers and artists. Especially in the processes of the cultural, audiovisual, books, phonographic and, more recently, electronic games industries, it is common that our creators are disposed of the flow and commercial rights of their creations, as well as of the derived revenues.

It is also possible to observe an enormous concentration of financial, human and technical resources in the cities of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, which is a characteristic that Professor Milton Santos has conceptualized as Concentrated Region (Santos et Silveira, 2001).

If nothing else, these weaknesses in cultural public policies, as well as in other areas of governmental action, it is usual to detect discontinuity of the actions as time goes by, isolation in relation to the other federal spheres and even in relation to other same-level governmental bodies, disarticulation within the same policy or body, and low or no dialogue at all between government and society in the definition of priorities.

The absence of structuring, articulated and long term policies, among other factors, constitute a scenario in which the Brazilian creative capacity, as verified in many countries, is characterized by the dependence on resources that are punctually made available by the State and, sometimes, by the market, being obliged to periodically dispute new resources for new productions, without the correspondent perception of revenues and rights that enable any sort of self-sustainability, besides having a consuming public that is reduced and largely dominated by foreign productions, normally rooted in millionaire strategies of communication and occupation of spaces for their promotion.

The immediate effect of these circumstances is that, in the Creative Economy field, it has always been very difficult for Brazilians to affirm themselves as a creator and flourishing center. At best, we are good cultural “doers”, but we rarely have control over what we do.

A single exception, which confirms the rule, is Rede Globo de Televisão (Rede Globo Television), that actually produces and exports contents and audiovisual formats in scale for several countries of the world, but whose vertical integration model and ownership of rights leads it to be also a factor of concentration in the domestic market, since talents and companies that associate with it are normally disposed of the rights and revenues over the works that they have performed, being also common that the companies belonging to such group operate in such a way that imposes entry barriers to new programmers and broadcasters in the Brazilian market.

2 THE EMERGENCE OF ANCINE

To face and to reverse this scenario in the audiovisual sector was the institutional role that the National Cinema Agency has imposed to itself since the beginning of its operation in 2002 (its creation took place in 2001 through Provisional Measure 2.228-1), and the purpose of this paper is to shed light on how such process has occurred, under the view of someone that has kept up with it from 2007 to 2017, first on the condition of adviser to the Board of Directors, and then as an Officer.

More than results, which exist and are noticeable, the most important here is to delimit the premisses that have oriented this rare case of success in the construction of structuring public policies, in consideration of its limitations, and to take a look at how this example may bring new perspectives for public policies designed to the broad range of sectors that constitute the Creative Economy in Brazil.

Indeed, as it may already be clear at this point, this is not an academic paper, even because it is not written by a scholar, but by an artist that has had the opportunity to act in cultural management for the last twenty years, and that does not have the intention to delimit the entire territory and to provide an ultimate reading on the subject. For this reason, I shall not take part in the debate over the best way to conceptualize cultural activities with economic purposes. Instead, for the purpose of this paper, terms as Cultural Economy and Creative Economy are equivalent, referring to a scope that encompasses arts and the so-called cultural industries, which takes into account since the typical processes of a market economy to the ones of the solidarity and shared collaborative economy, but not reaching segments such as advertising, design and fashion, in which the creative element is an input for sectors that do not have an immediate and central connection with the cultural fruition.

In this paper, I try to dialogue with something that Professor Ana Carla Fonseca Reis said in an article called Culture and Creative Economy in the sense that “it does little to defend the recognition of culture's economic potential, if an even more fundamental step has not been taken before: the design of a clear public policy based on the local context”. I believe that this is what we have been trying to do at Ancine.

As stated in the agency's website “Created in 2001 by Provisional Measure 2228-1, Ancine – National Cinema Agency is a regulatory agency that has as attributions the promotion, regulation and surveillance of the cinema and audiovisual market in Brazil. It is a special independent body, bound to the Ministry of Culture since 2003, with headquarters at the Federal District and Principal Office at Rio de Janeiro” (Ancine, 2017b).

Article 6 of the concerned Provisional Measure lists the objectives of Ancine:

I – to promote the national culture and the Portuguese language upon the stimulus to the development of the national cinematographic and videofonographic industry in its area of practice; II – to promote the programmatic, economic and financial integration of the governmental activities that relate to the cinematographic and videophonographic industry; III – to increase the competitiveness of the national cinematographic and videofonographic industry by the means of the promotion to the production, distribution and exhibition in the several market segments; IV – to promote the self-sustainability of the national cinematographic industry, aiming at the increase of the production and exhibition of the Brazilian cinematographic works; V – to promote the articulation of the several links of the national cinematographic industrial productive chain; VI – to stimulate the diversification of the national cinematographic and videophonographic production and the strengthening of the independent and regional productions, with the purpose of improving their offer and permanently enhancing their quality standard. VII – to stimulate the universalization of the access to cinematographic and videophonographic works, especially the national ones; VIII – to secure the diversified participation of foreign cinematographic and videophonographic works into the Brazilian market; IX – to secure the participation of cinematographic and videophonographic works of national production in all segments of the domestic market and to stimulate them in the foreign market; X – to stimulate the training of human resources and the technological development of the national cinematographic and videophonographic industry; XI – to look after the respect for copyrights regarding national and foreign audiovisual works (Brasil, 2001).

Reading these objectives reveals that Ancine was born with the mission of both protecting the Brazilian cinematographic and videophonographic production in face of the foreign cultural industry, seeking to promote self-sustainability and the strengthening of economic agents, and also making it in an articulated way between the several links of the cinema, video and television productive chain, bringing to its scope, beyond production, exhibition, flow, training and access.

The absence of mention to the broadcast sector within Ancine's regulatory scope should be noted, as a result of the political pressure of this sector to stay apart from any regulation, what is a sad reality in our country up to the present moment.

The aforementioned Provisional Measure also created the Superior Council of Cinema and charged it with the incumbency of formulating the public policies' directives, besides creating the Contribution to the Development of the National Cinematographic Industry – CONDECINE, that is levied on the propagation of audiovisual works of all market sectors, returning to the relevant sector and financing its own activities.

Along with this same movement of building an institutional framework, the government has restructured the Audiovisual Office (SAV), in the sphere of the Ministry of Culture, so as to take care of activities without an economic profile, such as training, conservation, festivals and short films, among others.

Upon the apparent dichotomy between the cultural and economic dimensions, reflecting a longtime conflict between filmmakers and producers regarding what should be the emphasis of the sectors' policy in Brazil, a clear division of attributions between SAV and Ancine has been adopted. However, the interdependence of these two dimensions has shown that, perhaps, this has not been the best path to follow, considering that each of these institutions had to deal, on their own way, with shading areas in the scope of their activities.

An example of shading area can be identified on short films. Short length content, that was previously considered as something economic unfeasible in the segment of Cinema and Television, therefore under SAV's typical scope, turned to acquire increasing commercial relevance in the universe of internet and Video on Demand. Even in TV, it started to be licensed for the purpose of complying with the duty to load independent Brazilian content by cable TV, or in the strategy of interleaved programs in the schedule, generating revenue to their producers and lifting their visibility – invading, thus, the typical scope of Ancine.

The lack of economic feasibility was associated with the lack of appropriate space for the promotion and commercialization of this kind of content, and not to their intrinsic nature, and a new technological and market reality revealed this potential, as well as revealed how anachronistic s this institutional arrangement.

It is important to stress that Ancine was born due to the articulation of the sector itself, involving producers, filmmakers, distributors, exhibitors and representatives of the television segment, that between June 28 and July 1st gathered in the city of Porto Alegre (Rio Grande do Sul State) for the 3rd Brazilian Cinema Congress.

Under the leadership of the filmmaker Gustavo Dahl, who would be later nominated as the first president of Ancine, 70 delegates representing 31 entities from nine states, besides 150 observers, discussed the situation of the true dismantlement lived by the Brazilian cinema at that moment, when the public institutions that supported the activity were extinguished in the beginning of the 90s by president Fernando Collor de Mello.

Ancince arise from the ambition and articulation of the audiovisual sector, which actively took part in the Executive Group for the Development of the Cinematographic Industry – GEDIC, instructed by the former president Fernando Henrique Cardoso in 2000, with the presence of representatives from nine ministries in order to search for solutions that would be capable to lift the activity in Brazil.

It is noteworthy that the agency originated from a diagnosis effort, performed by a multidisciplinary group, articulated with the public power, looking for an institutional solution that combined regulatory and financing capacities, which means that it was born with the mark of a systemic and articulated vision that would permeate its utter subsequent existence.

Such systemic vision had already been expressed, in a limited manner, in the way that laws disciplining tax incentives for the audiovisual domain were structured, that differently from Rouanet Law (Brasil, 1991), did not restrict themselves to sponsorship mechanisms, but invested in the synergy between different links of the productive chain, enabling investments from foreign distributors and programming companies in the co-production of independent Brazilian works, creating investment funds (FUNCINES) that act on every market segment, and actions of direct promotion with resources from the National Treasury based on the previous commercial and artistic performance in different segments, which came to be known as “Revenue Additional Prize” (PAR-production, PAR-distribution and PAR-exhibition) and the Ancine Quality Prize (PAQ).

Such concern had only occurred a few times in the trajectory of cultural public policies in Brazil. One of them was the creation of the Theater Promotion Law, in city of São Paulo, by January 2002, which did not focus on financing the production of works, but on the support to research processes of better structured theater groups, and that was born from the articulation of artists in a movement that became known as the Arts against Barbarism in the 1980 and 1990 decades of the XX century. This same movement would replicate years later among Dance professional, who conquered a law in the same footing.

Later, in the mandate of president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, a similar movement took place in the structuring of the Culture National System, in the policies for Diversity and Identity and in the establishment of the Cultura Viva (Live Culture) program, that emerged and structured themselves upon the intense mobilization of cultural managers and activists.

These reasonably successful initiatives are exceptions in the history of cultural policies in Brazil and reflect the paradigm shift brought by the ascension of the left-wing to federal government, but they currently suffer with discontinuity, isolation, disarticulation and irregularity – problems that characterize Brazilian public management –, being tough to precise, in the present moment, whether it is possible to affirm that the same challenge is posed to Ancine.

In the specific case of Ancine, considering its governing body, under the presidency of Manoel Rangel, and also government official that are specialist or technicians in regulation, some premisses have been practically forged in these 15 years of existence and have been successful in translating into practice the multidisciplinary and multifocal character in its conception, premisses that have sustained a vigorous process of formulation and management of policies for the sector. The latter can be mainly recognized upon the reading of successive regulatory agendas for the 2013-2014, 2015 and 2017-2018 biennium, which are available at Ancine's website (2017a) in the document Guidelines and Targets Plan for the Audiovisual Sector of 2013 (Ancine, 2013), and also in the definitions and objectives in the several Normative Instructions that have come into force along the years. It should be noted that the reference for the work of the agency has always been the experiences of the French CNC and the Directives of the European Parliament regarding audiovisual and communication services (União Europeia, 2010), which were the inspiration in the entire process.

I identify this set of premisses as follows:

Regulatory promotion – systemic and organic view in the structuring of promotion mechanisms and courses of action, aiming at achieving the several links that compose the productive chain of the audiovisual domain in synergy, acting, thus, on the unbalance existing in such market – with a clear logical subordination to the financing actions and to the needs of regulation, protection and promotion of the Brazilian audiovisual production in face of the market power or distributors, broadcasters and TV programmers, and in face of the north-American audiovisual industry.

Intellectual property – centrality granted to the power that producers have come to exercise over the Intellectual Property of their works, brands and formats, facing historical restrictions that usually divested the creators from the rights over their contents and derived revenues, what would jeopardize the capacity to reach the sustainability of their undertakings. Such centrality is clearly expressed in the Managing Power over the Audiovisual Work Patrimony brought by Normative Instruction No. 100 from 2012 (Ancine, 2012), but before that the definition of Brazilian independent production of cinematographic and videophonographic set forth by number V of Provisional Measure 2,228-1 designated it as “that whose producer company, holding the majority of the patrimonial rights over the work, does not have any association or bond, either direct or indirect, with companies that render broadcast services of sounds and images or pay-operators of mass electronic communication” (Brasil, 2001).

Cultural diversity – it relates to the identification and support to the different business models, as well as to the effort to actually nationalize the policies of promotion and regulation, reaching the entire national territory. The result obtained was the production and flow of works destined to the most diverse kinds of audience, sustained by the most different business models of all sizes, stimulating thus the complexity and sophistication of the production, distribution and public communication system as a whole. More recently, upon the Regulatory Agenda of 2017-2018, due to a militant work from government officials located at Ancine, genre and race matters have been introduced, with the purpose of broadening the participation of women, LGBTs and black people in the creative processes and in the management of audiovisual projects.

Market expansion – this premise involves the effort to broaden the number and the kind of cinema rooms through the country; the generation of demand, in television, for independent production's content; the strengthening of distributors and Brazilian TV programmers that operate preferentially with Brazilian works; the effort of internationalization of local productions and the emphasis granted to international co-productions; the investment in the production and flow of electronic games; and, more recently, the beginning of the debate over the regulation of Video on Demand. In all of these cases, the search for broadening the flow of national production has been accompanied by the effort to generate synergy and mutual commitment between the different links of the productive chains, for a greater participation both in the domestic market and in the international level.

3 THE GROWTH OF ANCINE

This set of premisses is subject both to the systemic vision brought by the setting up of the agency upon the engagement of the technical and managing body in the daily routine of the activity's regulation, and to the private sector that, despite of occasional divergences with the technical and managing body of the agency, knew how to converge on important issues, and on the way to face challenges in the context of the Brazilian scenario. It is relatively easy to inscribe objectives like these in the document that creates a public body, but the most difficult task is to materialize and sustain such construction as time goes by.

It is possible to show the positive results of this systemic vision in several ways, but I hereby stick to the one that I consider to be the most successful action in these 15 years: the creation and the strengthening of the Audiovisual Sectoral Fund (FSA).

The FSA was established by Brazilian Congress upon the enactment of Law 11,347, from December 28, 2006, and regulated by Decree 6,299, from December 12, 2007, by the former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

Its first actions were launched in the final of 2008 and it consolidated itself as the main financial instrument of the audiovisual sector with Law 12,485, from September 12, 2011, sanctioned by president Dilma Roussef.

Law 12,495 was the result of a four years struggle that gathered the entire audiovisual sector together with the National Congress. Among other important aspects, such law granted to the State the regulatory power over distinct layers of activities (production, programing, packaging and distribution, being the first three ones under Ancine's responsibility and the forth one under the responsibility of the National Telecommunications Agency – ANATEL), being no longer based on the kind of technology employed in the operation. The Law has also financially reinforced the FSA upon the charge expansion of CONDECINE to the sale of mobile phones, addressed the creation of quotes for Brazilian contents in the schedule of paid TV channels, quotes of channels that were programed by independent Brazilian companies (without bonds with broadcaster and operators in the offered packages, and the necessity to destine at least 30% of FSA's resources to the activities of economic agents in the Center-West, North and Northeast regions. Once again, it should be noted that the unexplainable absence of the open TV sector in the regulatory scope, that still remains apart from the strengthening of the independent production and from regional development.

This new reality has made it possible to formulate and to put into practice a broad articulated program that conjugated several modalities of promotion to operation and that invested roughly 1,2 billion Brazilian Reais in the sector called “Brazil of Every Screen”, once again with the support of former president Dilma Roussef.

At one go, the quantity of resources destined to the production, distribution, exhibition and programing for independent Brazilian companies has drastically multiplied, jumping from BRL 90 million, in 2011, to roughly BRL 700 million in the following year. At the same time, a regulation that was compatible with the convergent reality has been structured, there was an effective decentralization of resources beyond the Rio-São Paulo axis and an effective demand for national content on paid TV, factors that, when conjugated, effectively gave – for the first time –, a national scale that enable the long for self-sustainability in the audiovisual sector.

Another fundamental aspect to understand the huge change of scenario brought by FSA under the operational logic of the Brazil of Every Screen program is the availability of resources (in their greatest part) under the form of credit operations, or investment operations, in which the Fund participates in the revenue obtained by the project without taking any patrimonial rights, inverting the financing logic of non-repayable funds that characterized the promotion of the activity until then, increasing the responsibility with the artistic and commercial results of the works that, on its turn, started to contribute with their revenues to the sustenance of the financing system.

In terms of effective disbursement, FSA jumped from roughly BRL 30 million in 2011 to more than BRL 300 million in 2016, and from 50 contracted projects to more than 300 in the same period. Also in this time frame, credit for the construction and technological update of cinema rooms raised from BRL 2,5 million to more than BRL 75 million; Brazilian distributors became the main commercial agent of national works, distributing 85,9% of the ones that had been launched in cinema rooms in 2015; and the occupation of Brazilian movies in paid-TVs' program schedule grew from 1% to more than 10%, reaching more than 87 thousand hours of national content broadcasted in 2016. Between 2013 and 2016, the number of contracted companies beyond the Rio-São Paulo axis grew 24 times.

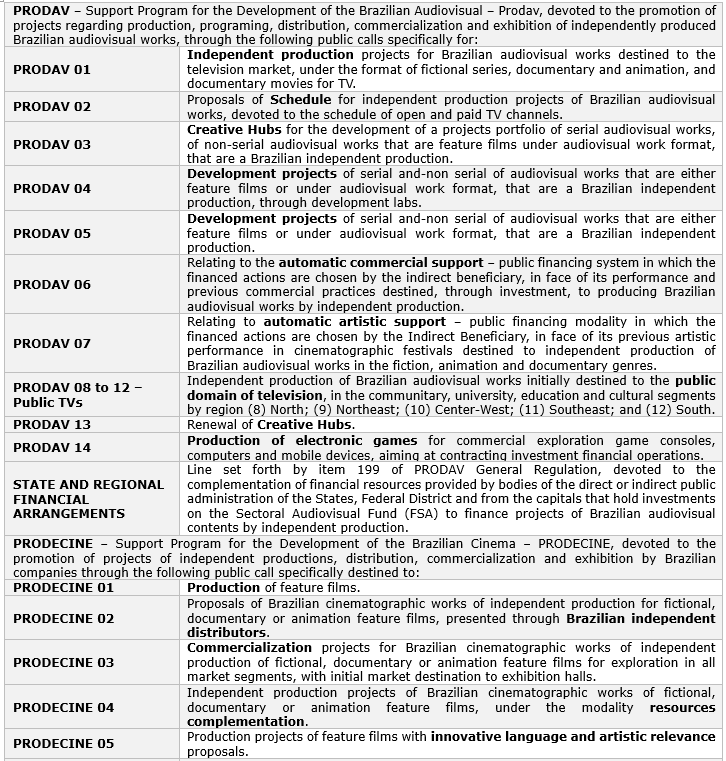

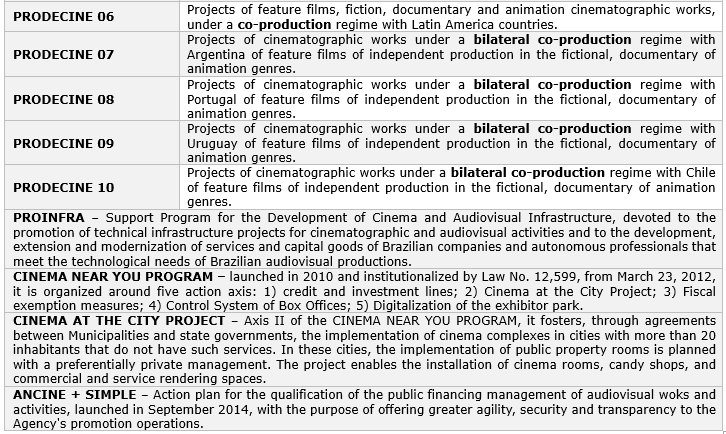

To a great extent, the responsibility for such success is due to the systemic and articulated way in which the promotion lines had been structured by FSA Management Committee, composed by representatives of society and from government, with the executive secretariat performed by Ancine, which set forth a range of action lines whose complexity can be perceived through the table below:

Table 1. FSA Lines of Promotion

A quick reading of FSA lines of action clearly reflects those public policy premises applied to the destination of resources.

First of all, the concern of falling upon the set of links of Cinema and Television productive chains; subsequently, to produce synergy between the involved actors, since, in the promotion lines, it is necessary to submit partnership agreements with distributors and programmers, also in the promotion lines to programing and distribution, the resources are always destined to co-production between the latter and independent producers that remain in the position of owners of the rights.

The action lines for cinematographic exhibition were initially directed to foster the creation of more rooms, as well as their digitalization, facing the extremely low density of the national exhibitor park, but, in a later moment, they also positioned themselves so as to produce a greater commitment between the schedule of complexes that make use of public resources and Brazilian cinematography, as it remains evident in the reformulation of rules for the use of incentive laws for such sector, that took place in 2017, and in the approval by FSA Management Committee, in the year, of a line destined that was destined to exhibitors for projects that involved the schedule of Brazilian works from independent production.

An exception should be pointed in the sense that, since the 30s of the XX century, Brazil has been practicing a policy of quotas in cinema rooms for Brazilian works, assuring a minimum quantity of days for the exhibition of Brazilian works in accordance with the size and number of rooms of each complex, and promoting some articulation between the segments of production, distribution and exhibition that, nonetheless, has never been enough.

Despite of the enormous and recognized advances, some aspects of the model brought by FSA are frequently questioned. For example, the private sector deems the participation of the Fund in the revenues of the financed works as excessive, what, in the composition with other investors and partners, would reduce significantly the Production Net Revenue, which is the main remuneration of producers. Other critics refer to the conditions of licensing and commercialization, also considered to be excessive and to allegedly “plaster” business and bring “undue” interference by the Public Power into the works' commercial lives, or even the predominance of an operational logic that is too focused on cinema, and that would not properly take into account the specificities of production activities to TV.

Another limit that has not been completely overcome is the small quantity of channels that are programed by independent Brazilian companies in the packages of paid TV, in view that the few that were successful at structuring themselves did not reach the best commercial conditions for their sustenance.

Within the agency, it is also possible to observe problems and inconsistencies that shall be faced, such as the disarray of the fund with promotion mechanisms through tax incentives, the excessive number of tender protocols and control points that hamper the operation and the necessity to evolve towards the promotion of projects portfolio and companies, and no longer each project individually considered.

One of the main weaknesses that have been detected by the public authorities, in the moment of Ancine's creation, was the lack of information and, consequently, of accumulated intelligence over the business of the sector that it aimed at regulating and fostering. Regardless of the nuisance beared by economic agents that are subject to the agency's surveillance, the fact is that it was also of their interest that the Public Power detained those information – that would not always be obtained in a consensual manner –, but that broadened the institutionality and professionalism of the relationships, together with forming a body of skilled specialists to operate the regulation of the market.

Fostering the Creative Economy requires, as a first step, the knowledge of the complexity of the relationships that take place within each sector of such economy, what is not always possible to obtain beforehand; knowing the way commercial relationships occur, which are the market failures of this market and its asymmetries; and how each segment develops different strategies and business models to sustain its project. Thereafter, the next step involves the positioning of promotion mechanisms in accordance with the strategic regulatory objective of the public policy, seeking to encompass the complexity of what exists without curbing the possibilities and solutions that shall be found along the process. It is not a trivial task.

Ancine sought to create a space of regulatory diversity, where each market agent may move in accordance with its features, without any predetermination or value judgment, because sustenance is not solely related to the capacity of economically keeping their undertakings, but, before, it relates to the existence of means that grant effective flow to the artistic objectives and time for them to find their audience. The perspective is to continue this model under the management of the first woman to assume the agency's presidency, Débora Ivanov.

I believe that Ancine's experience brings some perspectives to think about effective conceptual basis for public policies that are oriented towards the Creative Economy, hereby conceived in a sustainable manner, that is, in condition to further social justice and freedom of creation.

4 BASIS FOR A POLICY TO FOSTER THE CREATIVE ECONOMY

Considering the experience with the National Cinema Agency, I believe that it is possible to identify some basis for a policy to foster the Creative Economy.

Government must act in the decentralization of Intellectual Property and patrimonial rights over content as a way to balance the relationship between great communication conglomerates and other economic and cultural agents. The concentration of power in the hands of the first cannot be deemed as natural, nor happen as a necessary result of the possibilities brought by technological convergence. There is always a choice between making use of new technologies to distribute or concentrating rights and revenues. It is up to the Public Power to spotlight the possibilities of decentralization that this same convergence carries itself, and operate strongly in the sense of enlarging the freedom and the diversity of agents with operating and confrontation power. Income distribution is not enough, it is necessary to distribute property.

Besides, government must agree with market agents and society on a strategic future vision for its area of practice, providing general orientation and clearly conveying what it intends to reach, and the paths that shall be taken in order to get there. A participatory, democratic and plural planning is not only a guarantee of freedom for the citizens, but also a guarantee of continuity for the public policy. To make it possible, it is crucial to secure a strategy of stability for culture bodies, which occurs upon the existence of a technical body that is effective and qualified, but also through the establishment of goals and directives as the greatest possible range of entities and people involved in the sector. Participatory governance is what assures continuity, when policies are taken valuably by society.

The Public Power must foster and shelter the diversity of business models, kinds of companies and economic agents, different strategies of feasibility, and create a space for the exposure of conflicts and interests. In the field of the Creative Economy, modes of production that have a typical industrial character coexist and entwine with others that have collaborative and supportive features, sometimes within the same productive process. It is not the State's attribution to benefit one to the detriment of the other, nor to choose between one or another: the public policy must recognize what exists and not to choose what may exist. The complexity of negotiation models coexisting in the same field does not weakens, but broadens and strengthens the perception of rights.

The Public Power must create mechanisms to encompass all the federal levels in the formulation and maintenance of public policies, breaking with the tradition of isolation of the federal government in relation to States and Municipalities. More than that, I consider that the tendency to be followed by a public policy with federal coverage must be the gradual municipalization, mainly in a “presidential” country such as Brazil. Arts, like anything else, exist in the city. This is the territory where life takes place, and it is towards it that the State's action must tend to.

Government must always act under a systemic and articulated vision. Each mechanism of promotion must dialogue with its specific demand in a particular way, being also thought amidst a set of mechanisms that seek to encompass the totality and the complexity of the productive system. For example, a policy for the expansion of the number of cinema rooms needs to dialogue with the expansion of distributors committed to providing these schedules in their diversity, as well as the fact that a given policy to monitor the compliance with regulatory obligations must be able to collect data and produce knowledge to provide the regulated agent with information on behavior and trends of the market where it acts in. Currently, more than never, a significant part of our lives is articulated into networks, systems and rhizomes that generate interdependence and require exchange. It is up to the State to perceive and join such ambient, without the aim of seeking centrality or hegemony, because whenever the State extends its relevance disproportionately, the counterpart is a great dependence of society, increasing not only its responsibility beyond its capability, but also withdrawing from the ultimate goal, which is to expand the centrality of the citizen in the definition of policies.

Public Power must focus on the promotion of audience and in the generation of demand as a decisive strategy for the expansion of culture's consumer market. The role of creation is solely attributed to creators. It is not the State's role, under no circumstances, even under praiseworthy appearances, interfere on what shall be performed and who will be in charge of it, but solely to create democratic and egalitarian spaces with equal opportunities. Nonetheless, it is its role to inform and to form critical personnel for Culture, feeding the link of the productive chain that has the effective ability to feed and to sustain the others. This implies in recognizing the audience on the condition of users, and not merely cultural consumers. In the definition provided by Professor José Teixeira Coelho Neto, “the use of a cultural product entails that it is entirely enjoyed by the individual... that its, it implies that he is capable of identifying the origin and the ways of formal expression of such good in relation to its occasional content” (Netto, 1997). This necessarily leads us to think about the need for interaction of Culture and Education public policies.

5 A NEW BUREAUCRACY

By all means, it is possible to list more basis for public policies oriented towards the Creative Economy. The list above is the result of a personal experience and does not intend to be exhaustive or definitive, but mainly to call the attention for some conditions that may and must be observed.

In order to set forth theses basis consequent and effectively, something must be tackled, which is reinventing bureaucracy.

Government has the role of monitoring or inspecting the productive processes in the field of Culture, mainly when there are public resources involved in their performance. To exercise such role, the State needs a bureaucratic apparatus, under the Weberian conception of an organization endowed with rationality, impersonality and, above all, efficiency, and that is structured in a way to meet the purposes intended by the society that agreed on the laws and policy directives that orientate its course of action.

However, in Brazil, the bureaucratic rationality that serves the State to control processes and businesses in cultural field has never been the subject of an effective study on the nature of such processes. We have imported a legal and surveillance logic that had been created to inspect the construction of roads, the purchase of medicine for health centers, diverse service hiring, that we have been mistakenly trying to apply to cultural activity.

The result is not the “excess” of bureaucracy, as alleged by cultural producers, but an erroneous bureaucratic apparatus, which is much worse.

I hereby retrieve some of the arguments that I have exposed in my presentation to the Federal Senate, on the occasion of my designation to Ancine's Board of Directors, by the end of 2013 [1].

In the case of Brazil, the logic that has been assimilated was primarily set forth by Law 8,666 from June 1993, the so-called Bidding Law, which establishes in its first article the “general norms regarding bids and administrative contracts relating to works and services”. The organizing principle of such Law is that a certain service that is hired by the Public Administration must present a Basic Project that had been previously approved, also containing the “necessary and sufficient elements, with appropriate level of accuracy, to characterize a work or service”. Subsequently to the Basic Project, there must still have an absolutely detailed Executive Project that enables to objectively measure, on the occasion of provision of accounts, whether the hired service or acquired good corresponds to what had been agreed by the parties.

Notwithstanding, the execution of a cultural work is a collective process of construction that requires the combined intervention of several factors, being many of them perceived solely along the execution process. Such subjectivity constitutes the “Culture” object and determines a high degree of variability in the management of the financial, technical and human resources that are necessary to its performance. However, the literal interpretation of the legislation leads to the demand for an adequacy between the executed work or service to a Project that had been formulated much before its effective performance.

After more than 20 years applying the operational logic set forth by Law 8,666/93 to the field of Culture, one must recognize the lack of harmony between norm and fact that has been engendering a certain level of irrationality in the process as whole, entailing inefficiency both for the work of cultural agent and for the Public Power, what needs to be changed.

Society, through their legislators, has decided that, in Brazil, the State must foster cultural activity and, for that purpose, we need a great coalition effort to draw up a bureaucracy that is efficient and adequate, capable of securing the most important issue: the right to broad access to cultural diversity broad by the Brazilian citizens.

Also, in this regard, Ancine has initiated an import work that seeks to bring mechanisms of reality control closer to the cultural productive process, that has only been made possible by the accumulation of knowledge enabled by the regulatory and promotion activities.

Bureaucracy is necessary to produce equality, but it cannot be a constraint, nor allow the lack of commitment to the audience. For this reason, it is necessary, besides being the result of an intense and effective process of shared construction of a proper rationality between State, market and society.

6 CONCLUSION

According to economists, the etymological sense of the science that they investigate arises from the merger of the Greek words oikos (house) and nomos (laws, customs). In its origin, economy would be the way in which we organize the place where we live in, how we look after something so that life happens in the place where we are. Something like this.

In the Brazil of the XXI century, in the free, dynamic, but also competitive and profitable territory of production, flow and consumption of symbolic goods, it is necessary, in the first place, that we are capable of describing the house that we intend to build, and which rules shall govern the ones who inhabit it. If public policy is a tool to the construction of the house that shall be inhabited by the cultural economy in Brazil, then, before starting to prepare tender protocols, norms, programs and so on, the public manager must wonder how to contribute for the house to be large, fair and efficient enough so that life within it is fruitful and comfortable, perhaps happy.

It is certain that any mind is not enlightened enough to find an answer by herself. Without the active participation of society, it is not possible to build anything that fits its purpose. It is also certain that without a good planning and a strong notion of strategy, it is very likely that, as has already happened many times before, we start to build the house by the roof.

Thus far, the history of the National Cinema Agency can represent an inspiration and an example, but never a model to be followed and, for this reason, this paper insists on presenting premises and perspectives, but never ultimate truths. I hope to contribute both to whom operate and make use of policies for the promotion of the Cultural oikonomia.

REFERENCES

Agência Nacional do Cinema – Ancine (2012), Instrução Normativa nº 100 de 29 de maio de 2012. Dispõe sobre a regulamentação de dispositivos da Lei nº 12.485/2011 e dá outras providências. Ancine, maio 2012.

Agência Nacional do Cinema - Ancine (2013), Plano de diretrizes e Metas para o audiovisual – o Brasil de todos os Olhares para todas as Telas. Ancine, Rio de Janeiro, RJ.

Agência Nacional do Cinema – Ancine (2017a), Agenda Regulatória, available from: https://www.ancine.gov.br/pt-br/regulacao/agenda-regulatoria (Accessed in 2018 Jul 04).

Agência Nacional do Cinema – Ancine (2017b), Apresentação, available from: https://www.ancine.gov.br/pt-br/ancine/apresentacao (Accessed in 2018 Jul 04).

Agência Nacional do Cinema - Ancine (2017c), Uma nova política para o audiovisual: Agência Nacional do Cinema, os primeiros 15 anos. Ancine, Rio de Janeiro, RJ.

Brasil (1991), Lei nº 8.313, de 23 de dezembro de 1991. Restabelece princípios da Lei n° 7.505, de 2 de julho de 1986, institui o Programa Nacional de Apoio à Cultura (Pronac) e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União, dez. 1991.

Brasil (2001), Medida Provisória nº 2.228-1, de 6 de setembro de 2001. Estabelece princípios gerais da Política Nacional do Cinema, cria o Conselho Superior do Cinema e a Agência Nacional do Cinema - ANCINE, institui o Programa de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento do Cinema Nacional - PRODECINE, autoriza a criação de Fundos de Financiamento da Indústria Cinematográfica Nacional - FUNCINES, altera a legislação sobre a Contribuição para o Desenvolvimento da Indústria Cinematográfica Nacional e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União, set. 2001.

Netto, J. T. C. (1997), Dicionário Crítico de Política Cultural, Iluminuras, São Paulo, SP.

Santos, M.; Silveira, M. L. (2001), O Brasil: território e sociedade no início do século XXI. Record, Rio de Janeiro, RJ.

União Europeia (2010), Directiva 2010/13/UE do Parlamento Europeu e do Conselho de 10 de Março de 2010 relativa à coordenação de certas disposições legislativas, regulamentares e administrativas dos Estados-Membros respeitantes à oferta de serviços de comunicação social audiovisual. Jornal Oficial da União Europeia, 15 abr. 2010.

[1] http://ancine.gov.br/sites/default/files/apresentacoes/apresentacao-robertolima-senado.pdf

Received: 10 Jan 2017

Approved: 25 Jul 2018

DOI: 10.14488/BJOPM.2018.v15.n3.a9

How to cite: Monty, R. C. S. (2018), “Premisses for a Public Policy to Foster the Creative Economy: the case of Ancine”, Brazilian Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 15, No. 3, pp. 420-431, available from: https://bjopm.emnuvens.com.br/bjopm/article/view/431 (access year month day).