Environmental management practices for the sustainable development of a new city in Mozambique

Pedro Bettencourt Coutinho

nemus@nemus.pt

NEMUS, Lisboa, Portugal.

Nuno Silva

nemus@nemus.pt

NEMUS, Lisboa, Portugal.

Cláudia Fulgêncio

nemus@nemus.pt

NEMUS, Lisboa, Portugal.

Ângela Canas

nemus@nemus.pt

NEMUS, Lisboa, Portugal.

Sónia Alcobia

nemus@nemus.pt

NEMUS, Lisboa, Portugal.

Abstract

Careful urban planning is of extreme importance in Mozambique, a developing country with a fast-growing population. Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) and Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) are environmental management tools that can greatly benefit the planning process of sustainable urban spaces. This paper presents the contribution of SEA and ESIA to the environmental management of a new city in Mozambique, south of the Capital, Maputo, in the Katembe District. Katembe City’s environmental impact assessment process highlighted the particularities of this territory and identified the critical constraints for urban development and the requirements for minimization and monitorization of adverse impacts. The assessment process was developed sequentially, from a regional level to a local urban section level. In the preliminary assessment, major potential negative impacts were avoided and specific environmental and social detailed studies were defined, to be addressed in detailed urban plans. Following this, the detailed plans included all the necessary environmental requirements to avoid and mitigate several negative impacts, such as flooding, coastal erosion, biodiversity loss and habitat fragmentation. This case study emphasized the importance of SEA and ESIA in the planning process of the new city, resulting in a more sound and sustainable urban project.

Keywords: Mozambique; Sustainable Cities; Environmental Management.

1 Introduction

According to Godschalk (2004), for efficient urban planning the focus should be given not only to the conciliation of economics, environment and social and intergenerational equity, but also to the careful account of the territory.

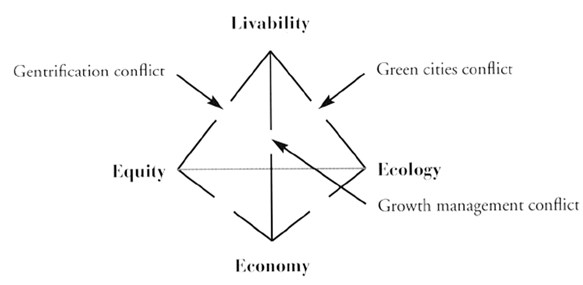

This integration is proposed within the sustainability / liveability prism, a framework for understanding and expressing the constraints of development (Figure 1). The dimension of liveability comprises the three-dimensional aspects of public space, such as mobility and architectural production, to which one can add spontaneous appropriation of public space, especially relevant in Mozambique and in Katembe. To achieve liveability the following key dimensions must be integrated and balanced (Grieve et Weinspach, 2010):

· Social and cultural capital, historical and ethnographic heritage; · Aspects of nature and environmental systems’ conservation and requalification required for human well-being; · Considerations of adequate and sufficient income to assure basic living conditions.

Figure 1. Sustainability / liveability prism

Source: Godschalk (2004)

Although the importance of liveability in the urban space has been considered for a while now, in later years it has been presented as especially critical for the general health of cities, particularly in developing countries (Jiboye, 2011; Rana, 2011; Wei, 2012; Lowe et al., 2015).

A new urban development of a territory usually introduces unbalances and tensions between these dimensions (conflicts in Figure 1), which are the result of pre-existing cultural aspects that are altered with a specific urban project (Godschalk, 2004). Hence, urban plans should be used to anticipate and prepare for a new equilibrium between these key dimensions, focusing on the population’s improved quality of life. In this process, it is particularly relevant to use a form of planning which is flexible, adaptive and includes the population’s participation.

Scale is very important when assessing and dealing with conflicts arising between sustainability dimensions and liveability, and a proposed effective way to deal with this would be the design of plans at each relevant scale, which should be integrated but also able to function on their own (Godschalk, 2004). In this context, the relationship among plans, places and people can be usefully understood as an ecology of plans (following the ecological alternative approaches of Steiner (2002) and Beatley et Manning (1997), which contribute to the creation of sustainable and liveable places.

When it is foreseen that a specific urban development can be linked to a major project (e.g. a major highway), attention to the regional scale can also be very valuable. In fact, the social and environmental effects derived from large projects are frequently not completely evident but can develop cumulatively through space and time. This is typically explored in cumulative impact assessments (Teixeira, 2013; IFC, 2013; Hegmann et al., 1999).

Although mostly understood as being applicable to a company’s performance regarding environmental concerns, environmental management practices can be usefully applied in urban management (cf. the discussion of sustainable urban transportation in Brazil in Maciel et al., 2013). In fact, SEA and ESIA exercises applied to urban plans are conceptually environmental management tools (Morrison-Saunders et Fischer, 2006) and incorporate environmental management practices such as the design of procedures for minimization and monitorization of (adverse) impacts on sustainable development.

The integration of plans of different spatial scales, proposed before, provides an additional opportunity for SEA and ESIA to be efficiently used in the environment management of the urban space, since the management procedures proposed in one phase can be revised and improved in the subsequent phase.

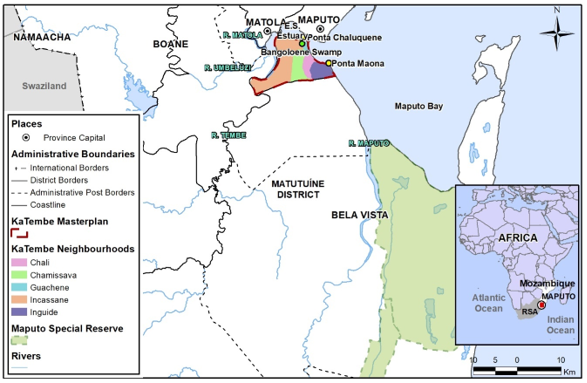

The study area in Southern Mozambique is limited in the North by the Espírito Santo Estuary and the Maputo Bay, in the East by the Indian Ocean, in the South by the South African Republic and in the West by the River Tembe and the dividing line between the administrative posts of Bela Vista and Catuane (Figure 2). It comprises the Municipal District of Katembe, and the District of Matutuíne, in the Maputo Province.

Katembe is a traditionally rural territory on the banks of Maputo Bay. While Maputo City is only 2 km away across the Espírito Santo estuary, the district of Katembe is currently 1 hour apart by ferry boat, and over 100 km apart through a not fully paved road, which is occasionally blocked in poor weather events.

The District of Matutuíne comprises Maputo Special Reserve (a pristine natural park in a coastal dune environment) and the scenic coastline extending from Machangulo in the North to Ponta do Ouro in the South. The Republic of South Africa’s border is nearly 90 km south of Katembe.

Figure 2. Katembe’s geographic background

Source: The author(s)’ own

This region, particularly the district of Katembe, is subjected to increasing pressure for urban development, due to the growing population of Maputo City, Mozambique’s Capital City. Considering the predictions of the National Institute for Statistics of Mozambique and the World Bank, it is expected that the population in the Maputo metropolitan area will double the present 2 million inhabitants in 20 to 30 years.

Expanding Maputo to the north is not an adequate option since its urban areas are already very constrained, and the havoc of unplanned urbanization is an unfortunate reality. Given the lack of options for the expansion of Maputo City, a major social problem in the region in the next decades is envisaged, mainly related to the lack of housing.

It is thus expected that, at least, part of the required expansion of Maputo will be made to the Katembe territory. A project to improve accessibility from Katembe to Maputo City is already under construction. The same project will position the South Africa border within a one-hour distance from Katembe and Maputo City’s centre.

The Katembe rural territory is already the stage of intense spontaneous land occupation with informal settlements and the transaction of land use rights (República de Moçambique, 1997). Hence and regardless of the improved accessibilities, Katembe’s native population is expected to increase from 19 thousand in 2007 to more than 40 thousand in the next decade.

Unplanned urban areas constitute a social problem because of the lack of pre-existent infrastructures required for adequate living conditions (roads, sanitation and utilities), aggravated by the unruled spatial distribution of housing, including low lying areas prone to flooding.

The worst-case scenario was foreseen and motivated the Mozambican Government’s decision to build a proper new urban centre in Katembe, to accommodate 400.000 inhabitants in the next 20-25 years. For this purpose, a complex planning process was initiated in 2011 and is still underway. To date, three major planning phases were accomplished, and the authors of this paper were the leading consultants (on behalf of Mozambique‘s Ministry of Public Works) for the strategic and environmental assessments (SEA and ESIA) (República Portuguesa, 2007; 2011; República de Moçambique, 2015b).

In this context, the present paper presents how Katembe’s environmental and social issues were used to shape the sustainable urban planning of the new city.

A state-owned company, Maputo Sul E.P., was created in July 2011, to prepare the planning process that was initiated in October of the same year. The urban plans and the environmental and social studies took place between 2011 and 2016. Following this, the city’s construction began in 2015, with its main accesses currently in completion: the bridge to Maputo City and the highway connecting to South Africa.

The planning for the new city followed ambitious objectives of environmental sustainability and social inclusion, in the aftermath of the disastrous effects of the floods of February 2000, which swamped the whole territory, took hundreds of lives and resulted in thousands of displaced people (Direcção Nacional de Gestão Ambiental, 2006).

Presented in the following sections are the Methodology of Katembe’s planning (section 2), the environmental and socioeconomic background (section 3), the environmental and social impact assessment (section 4), the discussion (section 5) and a summary and conclusion (section 6).

2 Methodology

Taking into account sustainability and liveability concerns, Katembe’s new city planning followed a sequential approach beginning with large scale planning (at a regional level), followed by medium-size planning (general or master plans) and concluding with local scale plans (urban detailed plans), thus incorporating four phases of planning, comprising different products, namely:

-

Regional Land Management Plan Katembe – Ponta do Ouro, for Katembe and Matutuíne Districts (Betar et al., 2012a);

-

Master Plan for the Urbanization of Katembe City (Betar et Promontório Architects, 2012);

-

Architecture and Urban Planning Partial Plans for Katembe City sections (Betar et Promontório Architects, 2013a; 2013b);

-

Engineering Projects for roads and accessibilities, bridges, water and sanitation, electricity and other.

Parallel to the planning process, and in an interactive way, environmental and social studies were developed, intended to and resulting in the integration of the sustainability and environmental issues in the planning process, derived from environmental management procedures:

-

Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Regional Katembe-Matutuine Land Management Plan (Betar et al., 2012b);

-

Background studies concerning river flow and flood risk assessment, climate change and coastal and estuarine hydrodynamics, and biodiversity and nature conservation (Betar et al., 2012c);

-

Environmental and Social Impact Assessment of Katembe City’s Master Plan (Betar et BETA, 2012);

-

Environmental and Social Impact Assessment of Urban Detail Plans for Katembe City sections 3 and 10 (Betar et BETA, 2013a; 2013b).

In this process, which engaged architecture, engineering, urban planning, and environment and social sciences’ teams, the development of specific studies concerning environmental and social vulnerabilities and risks was crucial for the planning process.

The planning and environmental and social assessment process comprised several instances for public and institutional participation, including public sessions, enabling the participation of citizens.

The first phase started with the Regional Land Management Plan for Katembe and Matutuíne Districts. At the same time the sustainability and social concerns of the region were addressed through a Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) exercise.

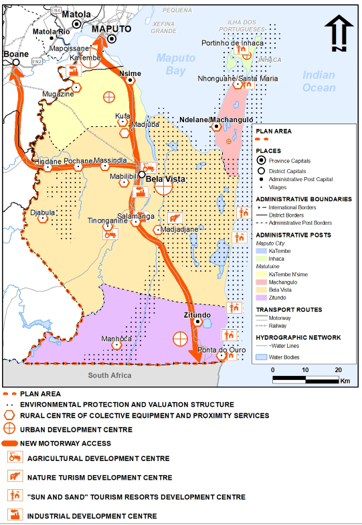

The SEA conducted the selection of the best location for the new city, as the principal urban centre in the region, while also assessing its main accessibilities: a suspended bridge across Maputo Bay to the North and West, and a highway connecting to the South African border to the South and East. Furthermore, the Regional Plan proposed a framework of secondary (smaller) urban developments, as well as a set of conservation areas, including a trans-boundary park (Libombos), connecting neighboring Swaziland and South Africa natural parks (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Land use model from Regional Land Management Plan Katembe – Ponta do Ouro

Source: Adapted from Betar et al. (2012a)

The second planning phase comprised the Master Plan for the Urbanization of Municipal District Katembe, where the main structure of the city was designed, including the location and composition of residential, commercial, touristic, leisure, recreational, industrial and mixed areas. This design was directly influenced by the ESIA process performed in parallel with the Master Plan. Both processes included public consultations, as well as a varied array of focus group discussions with NGOs, government officials and Maputo City Council planners and managers.

A set of specialized studies to address critical aspects of this territory were considered important in this design phase. The first comprised a study of coastal dynamics, coastal evolution and climate change potential risks, while the second included the assessment of river discharges and flooding risks (no less than six big rivers cross this region into Maputo Bay). A third study was dedicated to biodiversity and nature conservation.

With the conclusion of the second planning phase, regional and national authorities approved and published, in the Mozambican Government Official Gazette, the new city's Master Plan (Plano Parcial de Estrutura Urbana da Katembe). After a final set of public discussions, the Ministry of Environment issued a global environmental permit, including in the city's environmental license several restrictions and recommendations for environmental and social compliance.

The license required additional environmental studies to be conducted in the next planning phase, particularly to be addressed in the detail plans of each of the city's sectors (the Master Plan divided Katembe city in 13 major areas, each to be detailed by an urban detailed plan). The Ministry of Environment’s decision also included the need for a resettlement action plan for each of the city’s urban areas and for the construction of the city's territorial links (bridges, highways, harbors, etc.).

The third planning phase comprised the detailed design of the city's main urban sectors, as well as the detailed design of the principal infrastructure. This included the design of streets, roads, and parking areas, water, energy, and telecommunications networks, parks and recreational areas, sewage and water treatment plants.

This phase of the detailed design was also accompanied by environmental and social assessment processes, including one independent ESIA process for each urban sector. To date only two of these ESIA processes were concluded (priority areas number 3 and 10). The ESIA contributed to a more sound and sustainable urban design, having approached each territorial specification and vulnerability, either physical, ecological or social.

However, the critical issue in this third phase was the Resettlement planning. To build these urban sections the ESIA estimated that approximately 350 families in area 3, and 280 in area 10 would be displaced, either to adjacent rural areas (for those who decided to continue their farming activities) or to the new urban areas (for those opting to remain in the city). Two Resettlement Action Plans were thus initiated (one for each area); however, due to lack of government and municipal funding, these processes remain yet to be finished.

The territorial plans and environmental and social studies were revised and finally approved by the competent authorities: the Maputo Municipality Council and the Environment Ministry. The respective approval decisions were published in the Official Gazette.

After this phase, to further build planning and territory management consensus, the consolidation of the sustainability objectives requires the continuation of this process. Particularly in need is the completion of the participatory process regarding resettlement and social compensation of the affected population.

3 Background

3.1 Physical environment

Katembe‘s area is characterized by landforms gentle to nearly flat, forming a coastal plain composed of a wide sand dune system. The altimetry is under 50m, lowest at the riverside and alluvial plain of Bangoloene swamp (bellow 10m, 33% of the total city area). Some steep slopes are found in this coastal plain, associated to different erosion resistance of the geological units or with present sand extraction activities (Betar et BETA, 2012).

The hydrographic network is poorly developed in Katembe. The Espírito Santo Estuary, extending westward from Ponta Maona (Figure 2), has an irregular bathymetry (maximum depth of 18m and average 3-4m), characterized by sand platforms, a main channel, and tidal plains. In the right bank of the estuary (included in the Katembe area) there is a large tidal zone, where mangrove and other wet areas develop. In the same bank, progressing to Ponta Maona, the coastline presents an arch form with unsubmerged continuous and narrow sandy beach, bordered by a front dune chain. The Maputo Bay is a shallow inlet, where depths larger than 5m comprise only 35% of its area, mainly in the West part. The bank following Ponta Maona, is defined by cliffs.

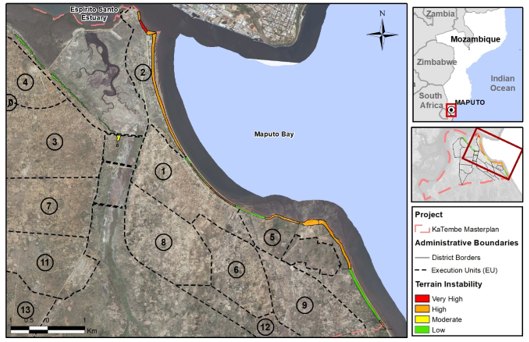

Due to the smooth terrain, the main erosion and slope instability risks are verified in the coastal area at the banks of estuary and Maputo Bay. The current most critical situation is verified in Ponta Chaluquene with very high instability and extensive erosion associated to river and tidal currents of the estuary. The situations of cliff instability are connected mainly to the effect of rainwater and surface runoff and translate a susceptibility to occurrence of slope mass movements. A high susceptibility to instability is found in the coastal arch extending to Ponta Maona, expressed by blocks’ fall or toppling (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Instability in Katembe’s coastal area

Source: Adapted from Betar et BETA (2012)

In the East estuary and Maputo Bay, accretion dominates over erosion in the long-term. Sediments are provided by river flows, but also by the erosion of cliffs and old reefs, in this case, especially due to surface runoff in the occurrence of cyclonic events and tropical storms.

The pressure over the coastal area is expected to increase with the urban development of Katembe, possibly affecting its function in inland protection from sea advance. The urbanization of coastal areas will increase the risks of cliff instability concerning the exposure of people and property. The possible sea level increase, related to global climate change, together with the gradual regularization of rivers and possible change in-land use in the watersheds may increase accretion of the estuary, increasing erosion in beaches bordering the bay.

3.2 Climate and water

The climate in the Maputo region is tropical, savanna-type and semi-arid. Precipitation is larger in the summer period, between November and March (73% of total annual precipitation of nearly 600 mm). The average air temperature varies between 27ºC in the summer and 21ºC in the winter. The coastal area can be affected by intense precipitation and winds during several days in the events of tropical cyclones, typically in summer time.

River Tembe (Figure 5) marks the West limit of Katembe territory. Its flow is markedly seasonal (Lencart e Silva et al., 2010), amounting to 140 M m3 annual average, produced in a hydrographic basin of 2.864 km2. Besides River Tembe, which extends for 125 km from the spring in Swaziland, the territory is characterized by the presence of the water course of Vale de Xandane/Bangoloene swamp, extending from South to North for 22 km. The Vale de Xandane water course presents a 109 km2 hydrographic basin, with annual average flow of 9 M m3, peaked (57%) in the October-January period.

The main tributary to the Espírito Santo Estuary is River Umbeluzi (Figure 2), with a hydrographic basin of 5.600 km2, and an extent of 314 km from its spring in Swaziland. The place of several large dams (including the Pequenos Libombos, the main water source of Maputo City), River Umbeluzi has a regular flow along the year, with average annual flow of 500 M m3 (Hoguane, 1999).

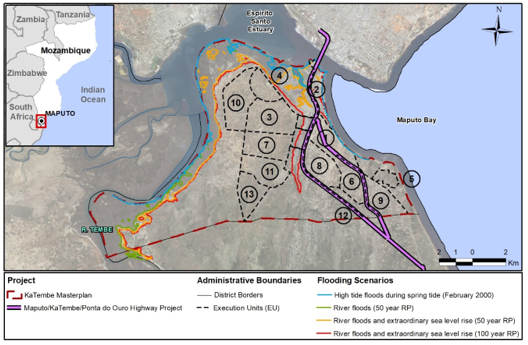

Floods have historical presence in the Espírito Santo Estuary banks, highlighting the event of Feb 2000 in the last decade, caused by intense precipitation and exceptional river flows. A specialized study of flood risk in the Katembe territory found that this area is more vulnerable to meteorological elevations of sea level (associated with atmospheric depressions) than to river caused floods. In fact, Katembe is protected from the most frequent floods by an estuary-side road and cliffs in the North, because the water course Vale de Xandane connects to the estuary through a hydraulic passage. The collapse of this dike or the change in the hydraulic passage could cause a dramatic increase of flood vulnerability of the Katembe territory.

In the flood risk assessment carried out, most of Katembe territory was classified with low risk. However, high risk areas are assessed in the areas connecting with Vale de Xandane water course and in the Northeast boundary, confining with the estuary: including the marginal road sided by the estuary and in some areas of the Guachene neighbourhood.

Figure 5. Flooded area limits in Katembe territory

Source: Adapted from Betar et BETA (2012)

In River Tembe the most important pollution sources are the domestic effluents, biomass combustion products and nutrients from farmlands along the river. These sources also affect directly the Espírito Santo Estuary and Maputo Bay, and additional pollution is generated by industrial effluents in Maputo and Matola and by the marine transportation operations in the Katembe pier and Maputo Port. In the tributary rivers, the domestic and industrial effluents are predominant water pollution sources.

Water quality is monitored only in the hydrographic basins of rivers Umbeluzi, Matola and Infulene, although not regularly. Main problems concern elevated turbidity, low dissolved oxygen, and high nutrient concentrations (ARA-Sul, 2010). In the estuary and Maputo Bay the water quality is degraded by human activities (Sete et al., 2002; Collin et al., 2008).

Groundwater is widely used in Katembe for public supply through bored or dug wells. Only the actual neighborhoods of Chali, Inguide and Guachene have tap water supplying systems, which are based on groundwater (10 m3/h). Access to water is a main source of daily hassle for the Katembe population. Besides using seven public supply wells, connected with the deep aquifer, the population explores 66 other groundwater sources, in the upper aquifer, for meeting its daily needs. The water sources are concentrated near the East and North limits of the territory, forcing the population to travel several kilometers to reach water.

The upper aquifer shows relatively high mineralization which can be caused by hydraulic connectivity with sea or estuarine water, geological origin, or eventual inadequate exploration of wells. This greatly limits its use for human or cattle consumption or for irrigation.

The perspective of the maintenance of sanitation problems in Katembe should cause the persistence or even aggravation of surface water quality problems in the territory. The unplanned expansion of urban areas, especially in the neighborhood of Guachene and northern coastal area of Chali neighborhood, should increase the exposure of population and property to floods.

It is expected that groundwater consumption will increase in the future, with the creation of new wells, given the probable expansion of the urban area of Maputo and the objective of the Mozambican Government to provide access of safe water to rural areas and towns all over the country (República de Moçambique, 2010; República de Moçambique, 2015a). New pressures may also arise, affecting groundwater quality.

Climate change, including higher air temperatures and a summer precipitation increase, and rise of sea surface levels, may have effects in the quality and quantity of groundwater. The expected sea level increase between 0,3 and 0,5m, in the period 1990-2100 (Santos et al., 2002) may accentuate the mineralization of coastal aquifers.

3.3 Biodiversity

Despite the human influence on Katembe territory, the presence of the estuary, the bay and the rivers, award the area a considerable ecological value.

Katembe intersects, only marginally, the Transfrontier Conservation Area of Libombos in the Southwest, established in 2000 between the Governments of Mozambique, Swaziland and South Africa.

The habitat with greater expression in Katembe is the semi-natural “agricultural fields and land with farming use” (54% of the area). Secondly, the group of “dense bushes and woods” (26% of the area, mostly in the South. Finally, “sand and silt tidal areas”, representing about 10% of the territory, mainly in the West. The Katembe area is divided in two (West and East) by the Bangoloene swamp, which includes a permanent water table and riverside vegetation patched with marshes.

Areas of very high ecological value located in the borders of the Katembe territory: mangrove areas in the banks of River Tembe (West) and bushes in the South, together with the Bangoloene swamp’s patch of marsh and riverside vegetation areas. The sand and silt tidal areas near River Tembe’s mouth and the Espírito Santo Estuary and the sand and bush dunes in the banks of Maputo Bay are ranked with high ecological value.

With the foreseen urban development of Katembe it is predicted that pressures on ecosystems will increase, through exploration of fauna resources, change in agriculture land-use, deforestation, water pollution, increased erosion in beaches and dunes, potentially affecting the river and coastal areas with highest ecological value.

3.4 Socioeconomics and community development

Land-use in Katembe territory is predominantly for farming and livestock (31%), wetland and flood plains at the bank of River Tembe and in Bangoloene swamp (19%), naturally wooded vegetation areas (15%) and farming lands patched with unplanned urban areas (12%). Actual urban areas, although with incomplete infrastructures and organized around unpaved roads, represent only 1% of the territory.

In the context of the City of Maputo, Katembe is the second municipal district with lower population (only 19.371 inhabitants in 2007 census, INE) and the population density is substantially smaller than the municipal districts in the north bank of Espírito Santo Estuary: 192 inhab./km2 facing 3.163 inhab./km2 in the whole City of Maputo.

The population of Katembe is concentrated in the Guachene and Chali neighborhoods (respectively 1.226 and 496 inhab./km2), with close access to Maputo center by ferryboat.

Inguide and Chamissava are the neighborhoods with largest population growth in the recent decades (3,86% and 6,84% growth per year between 1997-2007), probably due to overpopulation in the northern neighborhoods and the attractiveness of the road to Matutuine District Capital Bela Vista.

The actual urban spaces concentrate in Chali and extend to Guachene and Incassane along the coastline. Other unplanned urban spaces result from the densification of old informal settlements, around very narrow unpaved roads, with most houses made of concrete blocks or bricks. Disperse unplanned urban spaces have typically houses made of organic materials as wood (Figure 6).

Figure 6. House typical of disperse unplanned spaces

Source: Betar et BETA (2012)

Katembe’s local urban infrastructures, including roads, water supply and sewage and waste collection, are inadequate for the current population’s needs. There is no sewage or storm water drainage system.

Most of the active population of Katembe have informal jobs, predominantly in land cultivation and livestock farming activities (INE, 2007). The formal sector, employs only about 5% of the population in working age (from 15 to 65 years old). The population growth experienced in Katembe is not attended by an extension of employment in the formal sector, despite an important part of the population having basic education: only about half of Katembe’s population is illiterate (54%), relative to the country situation (72%).

Despite the fact that farming absorbs an important part of population of Katembe, agricultural production is pre-empted by adverse conditions, such as low soil fertility, lack of adequate infrastructure and accessibilities.

The territory includes one known archaeological site in Ponta Maona (Senna-Martinez, 1975), discovered in sequence of cliff instability. It is possible that other archaeological sites may yet to be discovered in Katembe’s coastal area and estuary and River Tembe’s banks.

Katembe is the place of expression of the intangible heritage of its population. It consists mainly in the maintenance of traditional burial grounds with some connection to natural environment (Betar et BETA, 2012).

It is foreseen, especially with the implementation of the Highway Maputo/Katembe/Ponta do Ouro, that Katembe territory will expand the urban areas. The unplanned pressure on natural or semi-natural areas of riverside and estuarine wetlands and the coastal zone may easily accomplish a degradation of Katembe’s landscape. The influx of population from Maputo City is continuous and by one estimate, even without the city's construction, the population of Katembe should reach a value between 54 to 89 thousand inhabitants by 2040, a value threefold or even higher than the 2007 level.

The growth of population should have an effect in housing numbers, but also in the economic activities of the territory. The development of small commerce and private public transportation by road, especially along the main roads, is foreseen. Farming production may show some decline.

It is possible that the material heritage may be conserved in conditions similarly to the present. However, an important threat to the known and yet to be discovered heritage is posed by continued erosion in the coastal area. The maintenance of the traditional burial grounds is also threatened by the weakening of community bonds and unsustainable exploitation of natural resources (Betar et BETA, 2012).

4 Environmental and Social Impacts and Measures

The environmental and social studies supporting the urban planning concluded that the building of a new city in Katembe could originate negative environmental and social impacts, even after a careful urban planning avoided most high-risk areas. Environmental residual impacts, classified with moderate to high significance, include:

· Local climate may be adversely altered in case closed city blocks are implemented;

· 21% of the territory may verify soil change and loss through soil sealing;

· Increased pressure on the coastal zone may affect cliff and sand dunes stability;

· Increase of groundwater consumption may compromise aquifer sustainability;

· Flood risk is moderate to high in the northeast of the territory, where the urban plans predict a low-density occupation;

· 15% of the planned urban areas overlap bush areas with very high ecological relevance.

Hence, most of the impacts correspond to the worsening of evolution trends already felt in the territory, as presented in section 3.

The environmental findings identified in the background studies of river flow and flood risk assessment, and also of climate change and coastal and estuarine hydrodynamics, were integrated in the urban plans as no-construction areas constitute coastline and watercourses protection buffers; all of these no-building proposals were respected in the Katembe City’s Master Plan: no urban development was proposed for high risk areas, and only low density urban areas were allowed in moderate risk areas.

Furthermore, the ESIA recommended additional measures to reduce residual negative impacts. From the set of proposed measures, the following are highlighted:

· Implementation of sand dunes stabilization and rehabilitation projects in Katembe’s coastal arch;

· Access to cliffs with high susceptibility to instability should be prevented;

· Specific geotechnical studies are required prior to any expansion or transformation of buildings located in the proximity to cliff edges;

· Implement a program for the monitorization and control of cliff evolution;

· Any new interventions in flood prone areas require detailed studies of flood risk;

· The Municipal Council should implement flood warning systems;

· A groundwater availability assessment study is required to define criteria for sustainable use;

· The Municipal Council should implement separative systems for rainwater collection and reuse;

· The new city should implement a network for water quality monitoring;

· An ecological and environmental requalification plan should be developed and implemented for the Bangoloene swamp;

· Building specifications in urban areas should ensure adequate ventilation conditions;

Regarding socioeconomic impacts, the most important negative impacts (moderate to high significance), concern the intensification of trends already present in Katembe‘s rural areas:

· Continuing spontaneous land occupation with informal settlements;

· Construction of new urban areas require previous relocation of rural families, impacting on farmers activities, local workshops, trade and services, with the potential to significantly affect families’ income;

· Migration of non-local people can cause cultural shocks with local populations;

· Eventual creation of a socially divided urban space, especially if Katembe is to become the site for the resettling population of the newly planned neighborhoods of Maputo City;

· Social exclusion of a significative part of the inhabitants, with lower incomes, in case public transportation system and pedestrian and bicycles networks are not implemented;

· Traditional burial sites may be adversely affected in case no specific protection is provided.

The sensible issue of cultural heritage is considered directly in the urban plans through safety and protection zones included as constraints to urbanization.

To deal with the residual negative socioeconomic impacts, the ESIAs proposed a set of minimization measures including the following recommendations:

· Assure the distribution of land to farmers’ cooperatives and associations;

· Avoid private condominium housing solutions;

· The Municipal Council should address future mobility needs and plan accordingly;

· Perform regular audits in the intervention areas of the approved detail plans to control unplanned developments;

· Assess the evolution of Katembe’s resident population, through regular surveys.

5 Discussion

Given Katembe’s physical, ecological and social backgrounds, the planning methodology for a sustainable and sound urban development, included:

· The sequential land management approach, progressing from a regional to a local level;

· The special focus on avoiding environmental risks at one initial stage of city planning (master plan level);

· The special focus on social, cultural and resettlement policies at the local (city’s sectorial areas) urban planning level.

In fact, the planning sequence enabled one interactive assessment of the territory firstly to address strategic issues (location of large housing projects, major infrastructure and accessibilities) at the regional scale, zoning land use in Katembe and Matutuíne districts, and selecting the areas with the most favorable environmental and socioeconomic conditions.

Secondly, flooding risks, coastal dynamics and ecological vulnerabilities were investigated in specific detailed studies, to define no construction areas in the Master Plan of the city, to adequately address physical and ecological concerns.

In the following third phase, more detailed approaches of community development, housing, cultural heritage and resettlement needs, were carried to achieve liveability objectives for the new urban developments.

The whole processed benefited from the close interaction of the urban and engineering planners on one side, and the environmental and social experts on the other. Also, the engagement of local communities, NGOs, public institutions and local authorities was essential and made possible through a continued participatory process.

Currently, the urban plans for Katembe have been discussed, approved, and published. Environmental studies have also been approved and are public domain. Resettlement plans have, until recently, yet to be concluded.

The major concerns for the next steps correspond to a proper implementation of the Master Plan, and the Sector Area Plans; governance, housing and resettlement, resource use, and account of environmental risks, all remain crucial for the successful implementation of the new city.

Due to the completion (expected in 2018) of the new bridge linking to Maputo's city center, Katembe‘s population is expected to rapidly increase, changing from the current low density, mostly rural, settlements where communitarian ancestral lifestyles prevail. Hence, the respect for local culture and land-use rights should be present in the application of different instruments of urban governance:

· Future urban management must be able to enhance the communitarian sense which characterizes today’s settlements, and be very strict in the control of spontaneous land occupation;

· The funding model for the city development should address different situations and goals. On one hand, funding must assure favorable conditions for low income settlements, sharing the costs of low income property development between donors, public and private entities. On the other hand, attracting potential promoters to medium to high income settlements is also critical (Betar et BETA, 2012);

· Urban development should be flexible enough to progressively integrate the information resulting from local partnerships and public participation (local communities and agents, and local authorities). Inclusive development should be regarded as an opportunity and not as a threat.

· To learn and profit from local urban experiences (e.g. inclusive housing and infrastructure projects by NGOs) is mandatory.

The redevelopment, rehabilitation and consolidation of the current settlements are very important for the development of the Katembe territory, because these are the areas that will ensure the specific (and unique) identity of the new city, and allow the preservation of cultural and patrimonial heritage. For the adequate development of the urban space the old and the new settlements should be connected, creating a city in the diversity.

Most of the area for residential use in the Katembe’s approved Master Plan is intended for social housing (54%). Due to this prominence, and taking into account social vulnerabilities, social housing should have a specific program, articulated with the Master Plan development, defining specific directives and objectives for each area. This definition should be based on the social objectives intended to be fulfilled in each community. In this process care should be taken to avoid social segregation. One integrated and spatially non-segregated social housing program should also foster the needed social control of urban spaces, to achieve increased security.

Focus on resource use is required due to the extended time horizon of the new city, and the need to address basic living means of low income population. Thus, it is crucial to manage resource demand (e.g. water, energy, farmland) through infrastructure optimization, and the design of the open space network (essential to water sustainability) and the mobility, local facilities, and buildings (essential to energy sustainability). It is also very important to monitor the environmental performance of the city, through the regular measurement of environmental and social indicators.

Environmental vulnerabilities and risks already existent in today’s Katembe, are expected to increase significantly in a near future. Hence, detailed geotechnical assessment should be performed previously to any construction works within 50 m inland from cliffs. Depending on specific findings, additional regulation measures can be implemented to ensure protection of coastal geomorphology. The intervention in flood prone areas also require preventive measures directed to construction projects, as well as contingency plans and adequate drainage infrastructure.

Water quality is essential to support existent and predicted uses, such as human supply and bathing. Development of Katembe City can exacerbate surface and ground water problems, hence implemented sanitation solutions will require follow-up and regular monitoring of water quality, in order to allow eventual corrections.

Most habitats of high to very high ecological value is protected (as these were integrated in a Green and Ecological Structure of the city). However, it is expected that these habitats should be subjected to additional anthropic pressure. Hence, additional measures might be required to ensure the preservation of notable and cultural landscape aspects.

According with the level of accounting of all these aspects in the city’s implementation process, different final scenarios for Katembe can be outlined:

· A fragmented city arising from mostly unplanned urbanization is influenced by the occasional land availability and by larger urban pressure. This scenario, linked with absence of a clear governance structure and of the lack of proper implementation of the environmental and social recommendations, facilitates the deterioration of urban and environmental quality: the outcome is a fragmented city, with social and cultural vulnerabilities and poor environmental records.

· A structured city: implemented according to the approved urban plans (master and sectorial) and recommendations (SEA and ESIAs), respecting the intended execution schedule, and achieving a high level of governance – the outcome is a sustainable and qualified urban environment.

6 Summary and Conclusions

This paper presents and discusses the methodology used to approach the urban planning of a new city in Katembe, South Mozambique, to accommodate the expected expansion of the Mozambican Capital City’s population.

Based on the perception that efficient urban planning and local development management is achieved through sustainability (economic, environmental, and social) but also liveability, a concept that comprises the three-dimensional aspects of public space and its spontaneous appropriation, a methodology for the urban planning of Katembe was designed.

This methodology, intending to ensure the planning process, is flexible, adaptive and includes stakeholders’ participation. Its main features are:

· Sequential approach in three phases from regional planning (first phase), following to master plan (second phase) and finally to local/sectorial planning (third phase);

· Integration, in each phase, of the urban planning with environmental and social approaches, comprising SEA (on the first phase, for regional planning) and ESIA (on the second and third phases, for Master and sectorial planning), together with specific studies concerning environmental and social risks;

· Several participatory instances for the public and institutions, available in the urban planning and environmental and social assessments’ individual processes, ensuring the involvement of stakeholders;

· Approval of urban plans and environmental and social studies by the competent municipality and environmental assessment authorities, engaging the governance institutions and fostering the required adaptation.

Central to this process was the perception of SEA and ESIA as tools for environmental management of the urban space in the early stages of development, aiming at a sustainable and liveable city.

Given the vulnerabilities and the environmental and social background of Katembe’s territory, the application of this methodology proved to be effective. Procedures for negative impact minimization were sequentially improved and subjected to the involvement of municipal authorities and the general population, through participation initiatives.

The first phase allowed territorial zoning and the identification of the area with the most favorable environmental and socioeconomic conditions for the city’s development. In the second phase, the city’s land use was further defined and restricted, taking into account the relevant environmental and social risks. Finally, in the last sectorial phase, specific issues concerning resettlement and neighborhood building were addressed.

Currently the first two phases are concluded, and the urban plans and environmental and social studies were approved and published. The completion of the last phase (sectorial planning) awaits the conclusion of the sectorial resettlement plans.

In this context, despite the availability of approved urban plans, the undesirable scenario of a fragmented city in Katembe could still become a reality, and the intended improvement of its population’s living conditions becoming relatively reduced. Spontaneous occupation of the territory could undermine the adequate planning and management of today’s and future settlements, making the concretization of the new city’s ambitious objectives very difficult.

Hence, major concerns for the next steps have to do with urban planning implementation issues, related to strengthening governance, adequate housing, settlement and resettlement policies, controlled resource use and account of environmental risks.

Provided that there is an adequate integration of these aspects, the accomplishment of a well-structured major city in Katembe is possible in a 20-30 year timeframe. The progressive implementation of the plans’ objectives and expected yields in the population’s living quality and land development should contribute to a significant sustainable development in this region.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to hereby thank for the discussions and their input, the colleagues who participated in the KaTembe Environmental Assessment Planning process, and in particular Tiago Mendonça (BETAR Consultores), João Luis Ferreira (Promontório Arquitectos), Pedro Afonso Fernandes (NEMUS) and Nelson Nunes (Maputo Sul EP).

Special thanks to Prof. Julio Wasserman (UFF Brasil) for his collaboration and review in the elaboration of this article.

References

ARA-Sul (2010), Estado da Qualidade de Água na Região Sul de Moçambique – Período de Abril a Junho de 2010 (Mozambique’s South Region Water Quality Situation – April to June, 2010), Administração Regional de Águas do Sul, Maputo, Moçambique.

Beatley, T.; Manning, K. (1997), The ecology of place: Planning for environment, economy, and community, Island Press, Washington, D.C., USA.

Betar; BETA (2012), Estudo de Impacto Ambiental do Plano Geral de Urbanização do Distrito Municipal da KaTembe (Environmental and Social Impact Assessment of Katembe City Master Plan), Conselho Municipal de Maputo and Empresa de Desenvolvimento de Maputo Sul, E.P., Maputo, Moçambique.

Betar; BETA (2013a), Estudo de Impacto Ambiental do Plano Parcial de Urbanização da Unidade de Execução 3 do Plano Geral de Urbanização do Distrito Municipal KaTembe (Environmental and Social Impact Assessment of Urban Detail Plan for Katembe City Section 3), Conselho Municipal de Maputo and Empresa de Desenvolvimento de Maputo Sul, E.P., Maputo, Moçambique.

Betar; BETA (2013b), Estudo de Impacto Ambiental do Plano Parcial de Urbanização da Unidade de Execução 10 do Plano Geral de Urbanização do Distrito Municipal KaTembe (Environmental and Social Impact Assessment of Urban Detail Plan for Katembe City Section 10), Conselho Municipal de Maputo and Empresa de Desenvolvimento de Maputo Sul, E.P., Maputo, Moçambique.

Betar et al. (2012a), Plano de Desenvolvimento Regional KaTembe – Ponta do Ouro (Regional Land Management Plan Katembe – Ponta do Ouro), Empresa de Desenvolvimento de Maputo Sul, E.P., Maputo, Moçambique.

Betar et al. (2012b), Avaliação Ambiental Estratégica do Plano de Desenvolvimento Regional KaTembe – Ponta do Ouro (Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Regional Katembe-Matutuine Land Management Plan), Empresa de Desenvolvimento de Maputo Sul, E.P., Maputo, Moçambique.

Betar et al. (2012c), Estudo de Hidrodinâmica na Baía de Maputo/Estuário do Espírito Santo, Empresa de Desenvolvimento de Maputo Sul, E.P., Maputo, Moçambique.

Betar; Promontório Architects (2012), Plano Geral de Urbanização do Distrito Municipal da KaTembe (Master Plan for the Urbanization of Katembe City), Empresa de Desenvolvimento de Maputo Sul, E.P., Maputo, Moçambique.

Betar; Promontório Architects (2013a), Plano Parcial de Urbanização da Unidade de Execução 3 do Distrito Municipal da KaTembe (Urban Planning Partial Plans for Katembe City Section 3), Empresa de Desenvolvimento de Maputo Sul, E.P., Maputo, Moçambique.

Betar; Promontório Architects (2013b), Plano Geral de Urbanização da Unidade de Execução 10 do Distrito Municipal da KaTembe (Urban Planning Partial Plans for Katembe City Section 3), Empresa de Desenvolvimento de Maputo Sul, E.P., Maputo, Moçambique.

Collin, B. et al. (2008), “Fecal Contaminants in Edible Bivalves from Maputo Bay, Mozambique: Seasonal Distribution, Pathogenesis and Antibiotic Resistance”, The Open Nutrition Journal, No. 2, pp. 86-93.

Direcção Nacional de Gestão Ambiental (2006), Avaliação das Experiências de Moçambique na Gestão de Desastres Climáticos (1999 a 2005) (Assessment of Mozambique’s experiences in climatic disasters’ management - 1999 to 2005), Ministério para a Coordenação da Acção Ambiental, Maputo, Moçambique.

Godschalk, D. (2004), “Land Use Planning Challenges: Coping with Conflicts in Visions of Sustainable Development and Livable Communities”, Journal of the American Planning Association, Vol. No. 1, pp. 5-13.

Grieve, J.; Weinspach, U. (2010), Capturing impacts of Leader and of measures to improve Quality of Life in rural areas, European Communities, Brüssel, Belgium.

Hegmann, G. et al. (1999), Cumulative Effects Assessment Practitioners Guide, AXYS Environmental Consulting Ltd. and the CEA Working Group for the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency, Hull, Quebec.

Hoguane, A. (1999), Sea Level Measurement and Analysis in the Western Indian Ocean, National Report Mozambique, Maputo, Moçambique.

IFC - International Finance Corporation (2013), Good Practice Handbook. Cumulative Impact Assessment and Management: Guidance for the Private Sector in Emerging Markets, International Finance Corporation, Washington D.C., USA.

INE; Censo 2007 - 2007’s Census (2007), Instituto Nacional de Estatística de Moçambique.

Jiboye, A. (2011), “Sustainable Urbanization: Issues and Challenges for Effective Urban Governance in Nigeria”, Journal of Sustainable Development, Vol. 4 No. 6, pp. 211-24.

Lencart e Silva, J. et al. (2010), “Buoyancy-stirring interactions in a subtropical embayment: a synthesis of measurements and model simulations in Maputo Bay, Mozambique”, African Journal of Marine Science, Vol. 32 No. 1, pp. 95-107.

Lowe, M. et al. (2015), “Planning healthy, liveable and sustainable cities: How can indicators inform policy?”, Urban Policy and Research, Vol. 33, No. 2, pp. 131-44.

Maciel, M. et al. (2013), “Issues and trends on sustainable transportation: the case of Brazilian cities (2003-2010)”, Brazilian Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 10 No. 2, pp. 43-56.

Morrison-Saunders, A.; Fischer, T. (2006), “What is wrong with EIA and SEA anyway? A sceptic’s perspective on sustainability assessment”, Journal of Environmental Assessment Policy and Management, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 19-39.

Rana, M. (2011), “Urbanization and sustainability: challenges and strategies for sustainable urban development in Bangladesh”, Environment, Development and Sustainability, Vol. 13 No. 1, pp. 237-56.

República de Moçambique (1997), “Lei n.º 19/97 de 1 de Outubro – Lei de Terras”, Boletim da República - I Série, No. 40, pp. 15-9.

República de Moçambique (2010), “Programa Quinquenal do Governo para 2010-2014”, Governo de Moçambique, Maputo, Moçambique, available from: www.portaldogoverno.gov.mz/por/content/download/1959/15690/version/1/file/Plano+Quinquenal+do+Governo+2010-14.pdf (Access: 22 December 2017).

República de Moçambique (2015a), “Decreto n.º 54/2015 de 31 de Dezembro - Regulamento Sobre o Processo de Avaliação do Impacto Ambiental”, Boletim da República - I Série, No. 104, pp. 484-503.

República de Moçambique (2015b), “Programa Quinquenal do Governo 2015-2019”, Governo de Moçambique, Maputo, Moçambique, available from: www.portaldogoverno.gov.mz/por/content/download/1960/15695/version/1/file/Plano+Quinquenal+do+Governo+2015-2019.pdf (Access: 22 December 2017).

República Portuguesa (2007), “Decreto-Lei n.º 232/2007 de 15 de Junho – Regime a que fica sujeita a avaliação dos efeitos de determinados planos e programas no ambiente”, Diário da República - 1ª Série, No. 114, pp. 3866-71.

República Portuguesa (2011), “Decreto-Lei n.º 58/2011 de 4 de Maio - Alteração ao Decreto -Lei n.º 232/2007, de 15 de Junho”, Diário da República - 1.ª Série, No. 86, p. 2533.

Santos, F. et al. (2002), Climate changes in Portugal. Scenarios, impacts and adaptation measures. SIAM Project, Gradiva/Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian/FCT, Lisboa, Portugal.

Senna-Martinez, J. (1975), “A Idade do Ferro em Moçambique: algumas notas para a compreensão da sua origem e difusão” (Iron Age in Mozambique: some notes for understanding its origin and diffusion), paper presented at Seminário de História de Moçambique Pré-Colonial, Universidade Eduardo Mondlane, Maputo, 1975.

Sete, C. et al. (2002), “Seasonal Variation of Tides, Currents, Salinity and Temperature along the Coast of Mozambique”, UNESCo (ICO) / Centro Nacional de Dados Oceanográficos.

Steiner, F. (2002), Human ecology: Following nature’s leaf, Island Press, Washington, D.C.

Teixeira, L. (2013), Megaprojetos no litoral norte paulista: o papel dos grandes empreendimentos de infraestrutura na transformação regional (Large projects in São Paulo’s northern coast: the role of big infrastructure projects in regional transformation), Tese de Doutorado em Ambiente e Sociedade, Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, SP.

Wei, Y. (2012), “Restructuring for growth in urban China: Transitional institutions, urban development, and spatial transformation”, Habitat International, Vol. 36 No. 3, pp. 396-405.

Received: Dec 30, 2017

Approved: Jan 10, 2018

DOI: 10.14488/BJOPM.2018.v15.n1.a10

How to cite: Coutinho, P. B. (2018), “Environmental management practices for the sustainable development of a new city in Mozambique”, Brazilian Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 112-126, available from: https://bjopm.emnuvens.com.br/bjopm/article/view/428 (access year month day).