A knowledge management perspective of the project management office

Jeniffer de Nadae1,Marly Monteiro de Carvalho1

1 University of São Paulo

Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to investigate the converting projects tacit knowledge into an available explicit knowledge in Project Management Offices, using the SECI model to analyze these processes. Using case studies, the information was gathered by in loco observation, interviews with PMO managers and project managers, and document analysis. The results show the socialization, externalization, combination and internalization, SECI in PMOs level, helping to visualize the process of transforming project tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge and to understand that knowledge must be incorporated into operational practices, rules in databases, and company history. Organizational culture was presented itself as a major factor, influencing this process of sharing knowledge among employees from the two companies studied. The steps of the spiral of knowledge, using the SECI model for the conversion of knowledge, the stage and how companies apply this conversion, show that these processes happen on a daily basis and continuously if the team understands this need. Project managers have to emphasizes the important of knowledge management, knowledge sharing and knowledge storage during the development of projects. Mainly PMO has an important role in the process of storage and sharing of knowledge.

Keywords: Knowledge Management, SECI model, Project Management Office, Brazilian Case Studies.

1 Introduction

Knowledge is a fluid mixture of framed experiences, values and contextual information, which provides a framework for assessing and incorporating new experiences and information, according to Davenport et Prusak (2000); while knowledge management (KM) essentially consists of processes and tools that are able to capture and share data. Those processes can apply and share knowledge between individuals within an organization (Nonaka et al., 2000).

Despite playing an important role in most organizations, affecting the performance and the success of both organizational and project (Davenport et al., 1998; Andersson et Linderoth, 2008; Davis, 2014; Hornstein, 2015) only recently knowledge management (KM) has been incorporated to the project management literature, making it a new and challenging field of study (Horstein, 2014).

Some representative studies of KM in PM perspective are the following: Bower et Walker (2007) whose study subject is planning knowledge management and their phases in projects; Ajmal et Koskinen (2008) analyzing knowledge transfer in the projects and the influence of organizational culture; Reich et al. (2008) knowledge management in IT projects; (Gladden, 2009; Alkhuraiji et al. (2016) how to manage and apply knowledge in organizations; Petter et Randolph (2009), the processes of reusing knowledge among projects; Tukel et al.(2010), knowledge and practice’s salvages; Johansson et al.. (2011), the importance of knowledge maturity to development projects; Aubry et al. (2011) the relation between organizational performance and the knowledge to the project management; Alin et al. (2011) knowledge transformation in projects; Gasik (2011) show a model of project knowledge management; Koskinen (2012) knowledge management as a factor that can improve project implementation; (Müller et al., 2013) project management knowledge in PMOs; Horstein (2014) knowledge as a factor of integration of projects.

In PM literature, studies on KM highlight the key role of the project management office (PMO) for storing and disseminating knowledge (Aubry et al., 2011; Müller et al., 2013; Pemsel et Wiewiora, 2013).

Projects are critical for knowledge creation, but the pool of knowledge is lost if there are no effective ways of managing (Fong et Kwok, 2009). It often occurs because the learning mechanisms of projects and firms, considering ‘memory’, ‘experience’ and ‘reflection’, have opposing features (Ibert, 2004). Knowledge accumulation is more likely to occur at the organizational memory level, while projects acquire new knowledge assets, since it promotes structural changes. Furthermore, an effective and successful KM requires more than new technologies and innovation; it requires the understanding and the aspects of the integration between humans and organizational culture (Davenport et al. 1998; Shand, 1998; Resende Junior et Reis, 2016).

Thus, from the organizational perspective, the PMO appears to complement the learning mechanisms that attempt to mitigate these opposing features of projects and firms. One of the functions of PMOs is to create and disseminate a PM methodology that synthesizes the best practices. Moreover, a PMO has a central role in organizing the PM communities of practice, Aubry et al. (2011) and fostering the networks and knowledge flows of project managers (Müller et al., 2013; Pemsel et Wiewiora, 2013). PMOs can support knowledge management by facilitating the centralization of knowledge acquired during the project lifecycle, gathering the lessons learned and converting the accumulated knowledge from project portfolios into routines, practices and processes, i.e., explicit organizational knowledge (Elonen et Artto, 2003; Hobbs et Aubry, 2010; Aubry et al., 2011; Denford et Chan, 2011; Rose, 2010; Unger et al., 2012). The KM functions pose several challenges for PMOs because they depend on investments, on organizational memory in the form of software and other IT tools, as well as on all stakeholders, who should be committed to sharing knowledge in projects. PMO must manage several processes, such as project reports, lessons learned, project revisions, post-project review, and stakeholder perceptions, in order to transform the tacit knowledge, created in projects, into explicit knowledge.

In this context, this paper aims to investigate the converting tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge in PMOs. This is a critical issue because; the tacit knowledge is often difficult to share comparing to explicit knowledge, which is documented and materialized by reports and other documents in the PMO (Nonaka et Takeuchi, 1997).

In order to help identifying the KM processes of socialization, externalization, internationalization and combination in PMOs, the SECI Model, proposed by Nonaka et Toyama (2003) was selected. The SECI model, proposed by Nonaka et Takeuchi (1997), helps to analyzing the spiral of knowledge creation, in which the interaction between tacit and explicit knowledge is amplified by the four conversion modes Socialization, Externalization, Combination and Internationalization. The spiral increases in scale as greater ontological levels are attained (Nonaka et Takeuchi, 1997; Nonaka et Toyama, 2003). The application of the SECI model to the PMO context can help understanding the factors that can influence KM processes to convert tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge, since it goes further in the current perspective of the communication and data storage, along with helping PMO with bridging the knowledge mechanisms of organizations and projects.

The methodological approach was a case-based research performed in two Brazilian companies. The information was gathered by: in loco observations, interviews with PMO managers and project managers, and document analysis.

Thereby this paper will analyze how the project knowledge into the selected companies is stored. Because of this we selected PMO members and project managers to be interviewed, and to understand all the process of project knowledge we will apply the SECI model, identifying all the stages of knowledge transformation and to help understand the converting tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge processes.

Considering the aforementioned objective, a summarized theoretical framework is presented to support the study in Section 2. In Section 3, the research methodology is presented. Its application surrounding the cases and their analysis are discussed in Section 4. Finally, conclusions are presented in section 5.

2 Theoretical Basis

2.1 Knowledge management

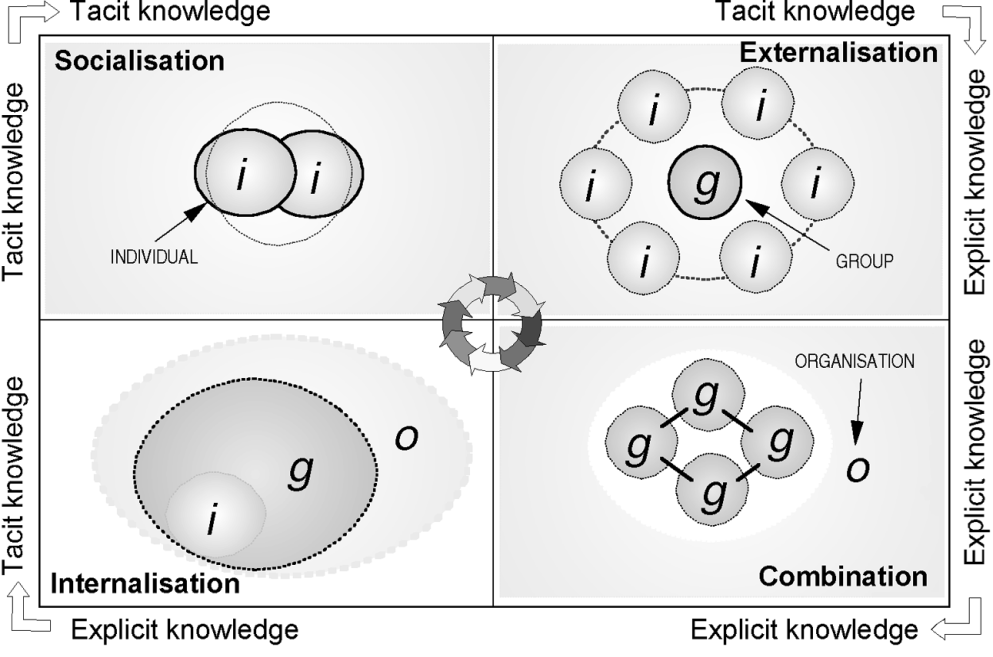

A model to represent the knowledge creation process was proposed by Nonaka et Takeuchi (1997), called SECI Model (Socialization; Externalization; Combination and Internationalization). This model presupposes that knowledge is created by the interaction between tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge, as shown in Figure 1. Thus, the model proposes four different ways for converting knowledge:

-

Socialization: turns tacit knowledge into tacit knowledge - individuals share knowledge and create tacit knowledge through direct experiences. Within organizations, individuals can embed tacit knowledge regarding clients through the experiences based on their interactions with such clients (Nonaka et Takeuchi, 2003).

-

Externalization: turns tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge - conversation is an effective method for articulating this process. For example, the sharing of tacit knowledge, which may differ among individuals, externalizes knowledge and becomes explicit. One technique for sharing knowledge is the application of analogies and metaphors, allowing individuals to establish connections to their real circumstances in which they live (Nonaka et Takeuchi, 2003).

-

Combination: turns explicit knowledge into explicit knowledge - Explicit knowledge transformation is articulated in the form of explicit knowledge through the combination process. This type of knowledge is acquired inside and outside the organizations. Thus, this knowledge is processed and combined to become shared knowledge (Nonaka et Takeuchi, 2003).

-

Internationalization: turns explicit knowledge into tacit knowledge - Explicit knowledge is created and shared throughout an entire organization; then it is converted into the tacit knowledge of individuals through the internationalization process. In this stage, an organization can offer employee training, write manuals, create documents, conduct experiments and simulations of the products and services offered, which can enrich the tacit knowledge of the individuals (Nonaka et Takeuchi, 2003).

Figure 1. The SECI model of knowledge creation

Source: Adapted from Nonaka et Toyama (2003, p. 5)

According to the SECI model, since knowledge is accumulated in each step, its conversion process is not cyclic but it is rather spiral, called knowledge spiral, because the knowledge is accumulated in each step. Knowledge is always improved upon, and acquired knowledge is added. The process of generating knowledge in a spiral is infinite. In the creation spiral of knowledge, the interaction between tacit and explicit knowledge is amplified by four conversion modes. The spiral increases in scale as higher ontological levels are attained (Nonaka et Takeuchi, 1997; Nonaka et Toyama, 2003). Knowledge that is created by the SECI process can trigger a new spiral of knowledge creation, moving through interaction communities, which transcend departmental and organizational boundaries, expanding horizontally and vertically. This knowledge can assist organizational departments in the innovation process (Nonaka et Toyama, 2003; Nowacki et Bachnik, 2016).

According to Watanabe et al. (2011), organizational culture is a great determinant in terms of how the members of an organization interact with one another. For example, an organizational culture that is open and that encourages discussion will promote communication and knowledge sharing; whereas an organizational culture that nurtures mistrust and power struggles will inhibit the free exchange and sharing of knowledge, which is used as a source of power among members.

Some authors explain that organizational culture is considered to be a critical factor in building and reinforcing knowledge creation and knowledge management, as it impacts the way members learn, acquire, and share knowledge (Gummer, 2000; Knapp et Yu, 1999; Alavi et Leidner, 2001; Gupta et Govindarajan, 2000; Martin, 2000). Although very little is known about how organizational culture enables or obstructs knowledge creation and its management in organizations (Rai, 2011), organizational culture has also been identified as the main hindrance for successfully managing knowledge (Bock, 1999; Knapp et Yu, 1999; De Long et Fahey, 2000; Rastogi, 2000; Ribere et Sitar, 2003).

2.2 The Project Management Office – PMO

The PMO concept emerged in the late 1950s and early 1960s (Kerzner, 2001). However, the PMO functions vary significantly, according to Dai et Wells (2004), and assume distinctive archetypes (Desouza et Evaristo, 2006). Hobbs et al. (2008) argue that PMOs are structures affected by company environments and organizational changes (Hurt et Thomas, 2009), which influence performance (Liu et Yetton, 2007; Aubry et Hobbs, 2011).

Patah et Carvalho (2009) have noted, a PMO is a structure that aims at connecting a project and an organization as a whole. Thus, PMOs is a structure for project management concepts and applications within an organization, assuming different functions: from a simple division for helping project control to a department in charge of all projects. Establishing a PMO is a strategy that can be employed to resolve these persistent problems—it is a source of centralized integration and a repository of knowledge, which can be applied to effectively inform project management (Desouza et Evaristo, 2006).

PMOs are also geared towards the application of project management concepts, which can support, through project management, the transformation of organizational strategies and results (Carvalho et Rabecchini Jr., 2005).

Following Dai et Wells (2004), a PMO can be defined as an organizational entity, established for supporting project managers and organizational teams regarding principles, practices, methodologies, tools, and project management techniques.

According to Desouza et Evaristo (2006), the primary purpose of a PMO is to centralize information in order to create a base of knowledge. Knowledge-intensive PMOs create collaborative communities for project managers, in order to enable the sharing of knowledge and learning, which can be difficult to capture and document through conventional mechanisms.

A PMO must be capable of managing retrospective learning, which refers to generating knowledge from past projects; and prospective learning, transferring knowledge from past experience to future projects (Pemsel et Wiewiora, 2013). A PMO can develop and maintain the rules and methods of a company. Procedural standards must be sufficiently detailed for providing guidance. However, such standards cannot be too strict because excessive strictness can inhibit team creativity.

Moreover, according to Aubry et al. (2011), the management of PM, related knowledge, is one of the key tasks of PMOs, that is, establishing the means and the ends for project managers and PMO members to share and access knowledge when needed. Despite the uniqueness of a project, the experiences from one project provide valuable lessons, which can be applied to other projects. Therefore, it is important to share knowledge across projects in order to avoid unnecessary reinventions of what has already been done (Carrillo, 2005).

Projects are sources of knowledge and are often regarded as efficient means for combining knowledge and thereby optimizing investments values (Pemsel et Wiewiora, 2013). Knowledge management is of crucial importance to an efficient project management. The growing complexity of project work equals an increasing number of technical and social relationships/interfaces that must be taken into account by project managers, when adapting knowledge and experiences from the daily work and previous projects of a company and from earlier projects (Ajmal et Koskinen, 2008).

KM within projects is often suboptimal within organizations because knowledge is created in one project, and then subsequently misplaced. One of the reasons for project failures is poor knowledge management: lack of effective project estimation and budgeting; poor communication and information sharing practices; inadequate reuse of past experiences and lessons learned; and insufficient understanding of the technology, particularly its limitations (Desouza et Evaristo, 2006).

For this reason, knowledge management, storage, interpretation and sharing is essential for organizations in order to maintain records, archives, documents, processes, reports, and group learning. In project-driven organizations, PMOs typically serve in this role. Poor performance of knowledge transfer results in wasted knowledge, unsuitable for reuse in other related projects. The lack of efficient knowledge transfer causes, in effect, unnecessary reinventions, errors, and time wastage. For example, in Australia construction projects, the cost of rework has been reported as being up to 35% of the total project costs and contributes to as much as 50% of the total overrun cost. In fact, rework is one of the primary factors contributing to the poor performance and productivity in Australian construction industry's poor performance and productivity.

A PMO can centralize the collection and storage of project knowledge, learned, along with models and methods applied. These records related to project performance can be stored in a database of learned lessons, such as status reports, variable analyses, changes in the initial plans, risk lists, and other information pertaining to successful or unsuccessful previous projects, which can be used for future projects (Elonen et Artto, 2003; Dai et Wells, 2004; Rose, 2010; Unger et al., 2012).

The development functions are those that involve recruitment, training and the development of project managers. The support functions are those offering guidance and clear project management processes. The control functions are those stemming from functional management and include: the assessment of project manager, the allocation of managers from one project to another, the guarantees for the production and presentation of project deliverables with proper quality; and the establishment of standards. PMO implementation can be challenging, but it is not an untapped territory. Many organizations, both large and small, have observed the benefits a consistent project control can offer (Hallows, 2002; Koskinen, 2004; Patah et Carvalho, 2009; Marra et al., 2012).

Martins et al. (2005) emphasizes the relevance of a PMO respecting company culture, especially with respect to the development of project managers’ skills. The notion of culture in a project management context is complex because projects involve a number of experts from various fields, backgrounds and professions, who typically have their own cultures and ways of working, which are not necessarily in harmony with one another or with the prevailing culture of the entire project (Ajmal et Koskinen, 2008). These cultural differences can either be a source of creativity, broadening perspectives on organizational issues, or they can be a source of difficulty and miscommunication (Sudhakar, 2015).

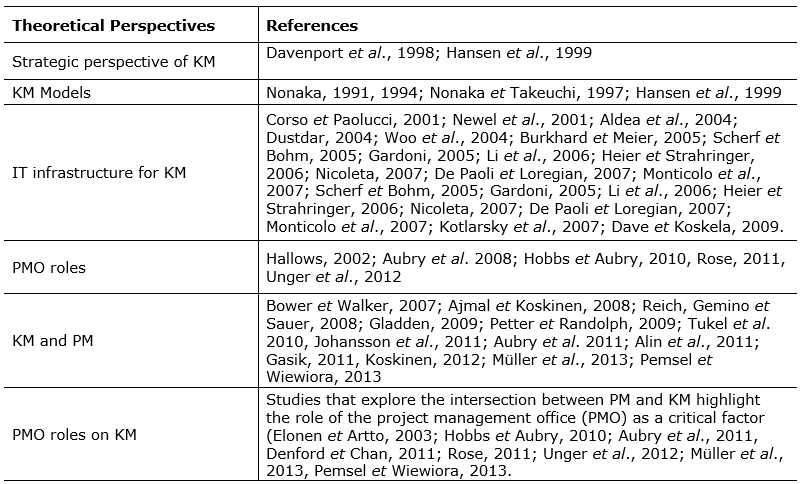

In this literature review, different general aspects of KM were presented. In addition to describing the role of PMO, the summarized Table 1 presents different perspectives, affecting KM on PMO perspective, in order to help identifying some authors and themes that can be explored.

Table 1. Theoretical framework for analyzing KM perspectives of the PMO

3 Material and methods

This study aims to investigate the converting projects tacit knowledge into an available explicit knowledge and into PMOs. For the case studies, two Brazilian companies were selected. According to Yin (2003), case studies allow analytic conclusions that contribute to the cross-case analysis of organizations. In addition to increasing external validity, this method provides protection from biasness (Voss et Frohlich, 2002).

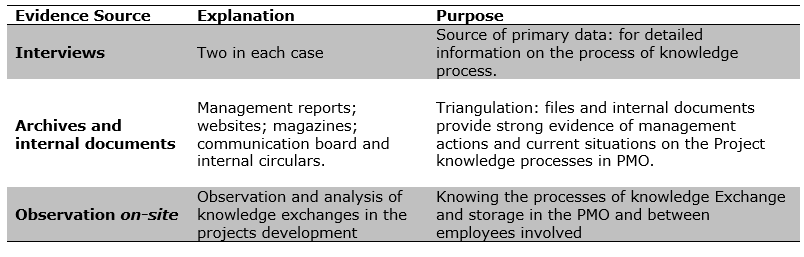

The qualitative method was applied in the present study. The criteria for the case selection included the following aspects: having a PMO, developing knowledge management practices, and being available for the research and for receiving visits from researchers. Evidence source are shown in Table 2.

The interviews were conducted in the companies and involved the following aspects:

• Project management, specifically, the project management structure, the importance of the PMO, its main roles and goals;

• Knowledge management, emphasizing the transformation of tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge focused on the SECI model.

Table 2. Evidence source

The interview script was divided into three sections. The first section aimed to obtain general information on companies, including project scope and the number of people participating. In the second section, we attempted to understand the importance of PMO in the organizations considering: the products manufactured; how long the PMO existed; the goals and functions of PMO within the organization; organizational structure; and the objectives of the coordinator regarding knowledge management. The third section addresses the issues surrounding the knowledge management of the organizations, particularly the process of transforming tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge and organizational knowledge storage techniques based on the model.

The two interviews were recorded and transcribed in each selected company; one was conducted with the project manager and another with the most experienced project manager (these interviews were conducted on different days). The transcribed interviews were presented to the interviewees for ensuring validity and reliability. The PMO archival data and interviews were employed to achieve triangulation, as presented in the following sections in Table 3. The discrepancies amongst these sources of evidence were noted and discussed.

After the interviews were conducted and the results obtained, the cases were compared and presented through charts, tables and a theoretical framework supporting the conclusions.

4 Results

Two companies have been selected for this study; both companies are located at the central-western region of Sao Paulo state. They meet the selection criteria of having formally established PMOs in its organizational structure. In order to preserve the identity of the selected companies, they will be referred to as Company 1 and Company 2.

4.1 Company 1

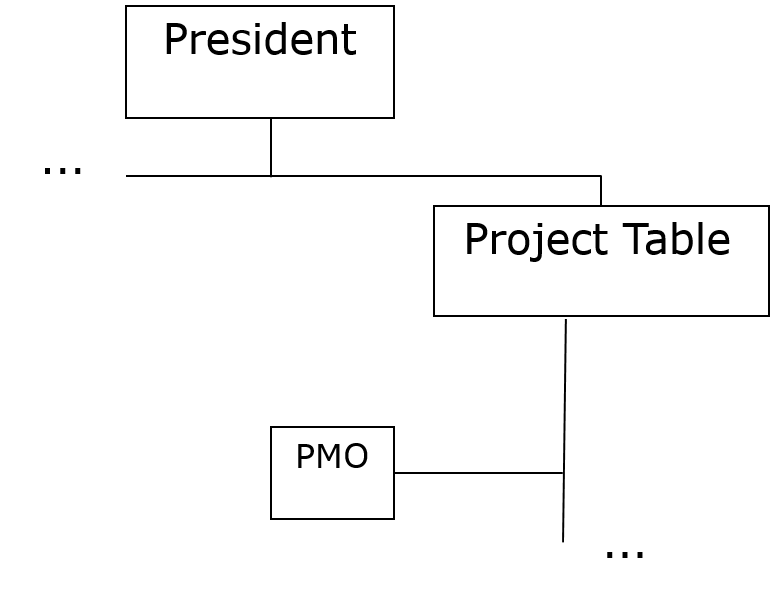

Company 1 currently has 400 employees and operates in the following industries: agricultural supplies, electric barbecue grills and furniture manufacturing. The PMO is still being established and 37 employees are being trained regarding the awareness of the importance of project management and the organizational role of PMO. The PMO is placed in an organizational structure at the second hierarchical level for directly reporting to project director (see Figure 2). The PMO currently has five full-time employees. Product development projects of this company are prioritized according to their deadlines. Many products are exported; therefore, many stages of the production process are modified to meet this specific demand.

Figure 2. The PMO in Company 1

The type of project developed is a new product design and it is developed, on average, ten (10) per year. The team is distributed according to their levels of experience and specialties, when several projects are being developed simultaneously. An example is when an employee who is the most experienced in a determined project will become project manager of a similar future project. In this case, the deadline that is agreed upon in the contract is prioritized.

When a project is successful, the project manager writes a report of the successful activities. Its team also attends a meeting with other departments (quality, marketing/sales and production) for discussing and sharing opinions regarding mistakes. Every project mistake and success is discussed, recorded and stored in a database created by the organization.

According to interviews employees considered their manager to be an open-minded leader regarding employees, new techniques, tools, and organizational learning methodologies.

The work team is composed of young employees who are still in school and others who frequently participate in courses and trainings offered by the organization. The employees are consistently learning new techniques and new methods for developing their activities and attempting to apply them in their organizational routine. According to the manager, new techniques and methods were developed for improving the traditional ones, such as new informational e-mails, IT programs, daily reports and others. These practices help the company to remain updated.

The company constantly invests in courses and trainings for its employees. According to the manager interviewed, the only prerequisite is that their employees have to explain their motivation for attending the sponsored course. Currently, sixteen employees are getting their MBA in project management for two reasons: first, for a better understanding and application of the knowledge acquired during the course; second because they felt the need for seeking more knowledge in order to improve their work performance. During the time of this research, others were also studying leadership, IT courses, communications and management.

4.2 Company 2

Company 2 currently has 3,000 employees. The products include agricultural supplies, gym equipment, plastic containers, other pieces, hoses and pipes, and other goods.

Its PMO is located at a strategic level and directly reports to the higher management level. The department is more involved in strategic decisions of the company (see Figure 3). It encompasses the seven subsidiaries of the group, with 22 employees. Four employees work exclusively on Research and Development (R&D), and the other employees work on projects focusing on new products for meeting market demand.

The types of project developed are new product design and developments of new technologies applied in current products and are developed, on average, eight (8) per year.

Figure 3. The PMO in Company 2

The PMO is coordinated by a mechanical engineering doctoral candidate who keeps informed on KM in PMOs through books and reports, which help him understanding the importance of knowledge management for the departments, in special for development projects. He admits that many knowledge storage processes must be improved; however, its improvement is not a priority of his department due to lack of time. According to him, the development of the projects in accordance with the industry priorities and stakeholders are the top priority.

The departments of projects, sales, R&D, quality and production work together as a team, organizing many meetings aiming at developing and designing new products while also improving existing products. All members are praised when a project is successful, since they all had contributed to its success.

According to the interviewee, all meetings are recorded for future consultancy, since they can present new ideas, from an employee that may not be used in the present, but who could be useful in the future. All progress is documented and stored from the beginning of each project. The members hold meetings for sharing the stages of development with frequency.

Whether successful or not, the stages are recorded and stored for ensuring access for the members to refer back to the topics discussed.

He also assures that the functions and organizational goals are clear to the remaining office team members. Everyone is aware of the importance of PMO and is stimulated to design new methods to improve knowledge sharing amongst employees.

One employee had an idea to create notice boards that they called "Communication Management", which are located in strategic places and scattered over the entire shop floor. The project, quality and production departments communicate through a tool known as "Communication Management". In addition, all employees can see and understand the current and subsequent stages of a project.

Additionally, these notice boards have specific information from the meetings and what must be remembered during the stages of the projects. This tool has proven to be important, particularly for the shop floor employees, who had previously felt excluded from the meetings and believed that they were the last ones to know about changes within the company. Now, shop floor employees feel more involved in the organization and in other departments.

This “Communication Management” can be considered a good knowledge sharing method among employees.

The interviews and analysis of documents and observation in loco helped characterizing Company 1 and Company 2 along with proving more information on their structure.

4.3 Cross-case study analysis

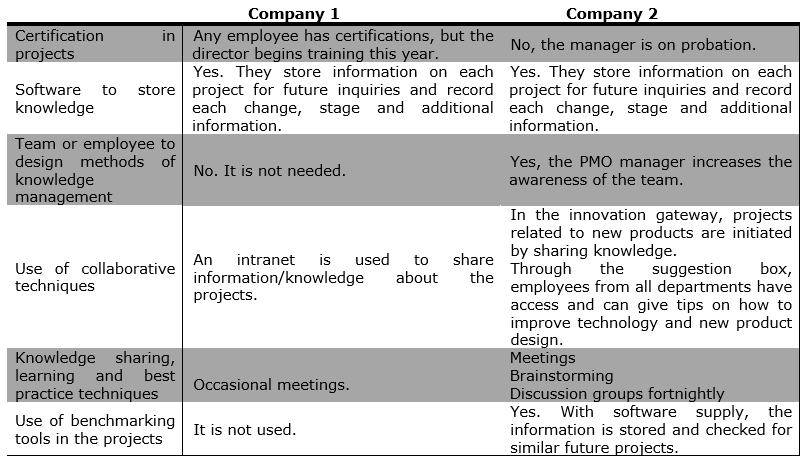

Table 3 presents summarized companies’ comparison. Both companies have projects involving the development of new products, aiming at meeting the demand and new market niches since product market is highly competitive.

Table 3. Cross-case analysis – characterization of companies and PMOs

The directors of Company 1 have a strong influence on project decision-making, and it often causes uneasiness among the employees. The same situation exists in Company 2. In addition, the president influences the decision-making processes and often provides ideas for new products. However, as reported by the area manager, those ideas are often not appropriately based on research and market needs, leading to conflict between the employees and the president.

It is important to highlight that both companies are family-owned enterprises and the higher-level management team is composed by company founder´s heirs. It is observed that in both companies, decision-making is centralized, which Elonen et Artto (2003) refer to as decisions based on the power of stakeholders. This centralization causes employees to feel insecure inhibiting their initiative and autonomy (empowerment).

According to the reports from Company 2, the most unsuccessful projects were managed by family members in higher-level management who insisted on the design of products that did not meet the needs of the market.

The accumulation and sharing of knowledge between individuals depends on the structure, culture and technology available in the organizations (Randeree, 2006). The companies analyzed have organizational structure and available technology serving as fundamental tools for the retention and sharing of knowledge between individuals; however, the organizational culture of Company 2 includes a PMO manager who is with his team on a daily basis. The manager of Company 1 does not believe that it is necessary to create methods and tools or to educate employees on the importance of knowledge management, such as bellow:

“This company had no method of knowledge management (storing or sharing) for a long time. Over time the developers brought in the techniques of knowledge management and we started to implement it in the company gradually. Today, we are still implementing some knowledge management processes, but we are not giving it priority since it is not an imposition of the high administration. We are implementing it because we want to improve the processes because it is not mandatory. Maybe this is why we prioritize the development of projects, customer deliveries and, when we have some extra time, we work to improve our knowledge management slowly. The culture of this organization is always “to make the deliveries requested by the client; therefore, other actions cease to be prioritized”. Manager of the Company 1."

As explained by Isaa et Haddad (2008), the organizational culture can enhance mutual trust in an organization and can help enabling a more effective knowledge transfer.

Some authors explain that the organizational culture is considered to be a critical factor in building and reinforcing knowledge creation and knowledge management in organization as it impacts how members learn, acquire, and share knowledge (Gummer, 1998; Knapp et Yu, 1999; Alavi et Leidner, 2001; Gupta et Govindarajan, 2000; Martin, 2000).

Company 2 presents an organizational culture that encourages open discussion and promotes communication and knowledge sharing (Watanabe et al., 2011), unlike Company 1 whose manager believes that knowledge management is a priority. Notwithstanding, the two companies make structure and technology available, in addition to applying techniques for maintaining and sharing knowledge.

4.4 Knowledge Management Analysis in the PMOs

Both companies have distinctive PMO implementation process phases. Company 1 is still facing a structuring process; knowledge management is not a priority because of the demands in terms of structuring the methodology for project management. Conversely, the PMO of Company 2 is already well structured and many questions related to knowledge management have already emerged.

The greatest difficulty reported by the companies is the conversion of tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge from the individuals.

According to Nonaka et Takeuchi (1995), it is often difficult to express tacit knowledge directly in words; the only means of presenting tacit knowledge is through metaphors, drawing or other various forms of expression that do not involve the formal use of language.

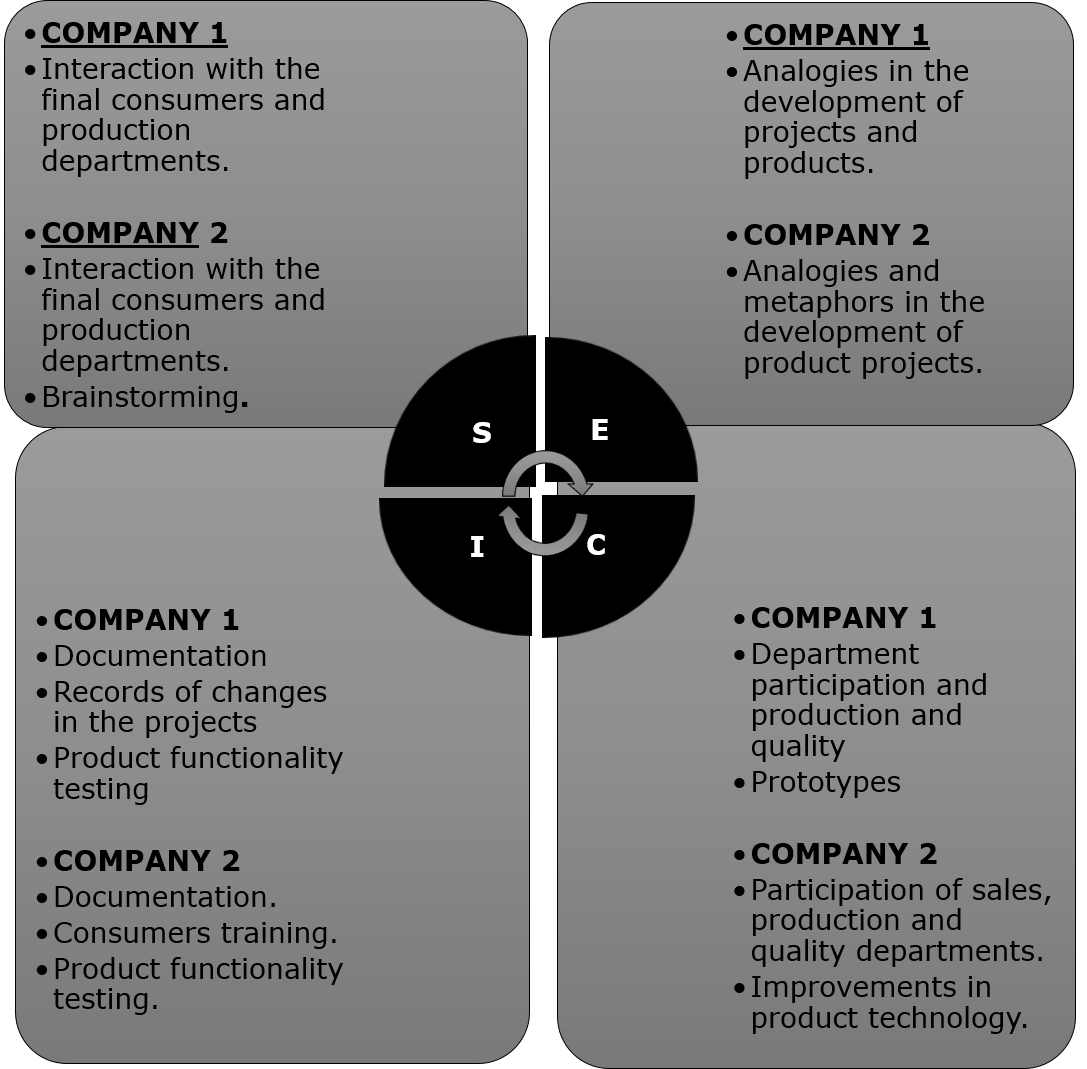

The SECI model proposed by Nonaka et Toyama (2003) assists in understanding the stages of the process (see Figure 4). In the socialization process, companies seek the transformation of tacit knowledge into tacit knowledge through the integration with the final clients and the production department. Company 1 applies this technique along with brainstorming for helping its employees with the sharing of their experiences and knowledge.

The externalization process seeks to turn tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge. In this phase, Company 1 uses analogies to the competitor products for naming their projects suggesting a goal to be overtaken. Company 2 uses analogies and metaphors for developing products and for naming projects. The products presenting similarities to parts of the human body, developed by Company 2, have its project referring to such parts.

In the transformation of explicit knowledge into explicit knowledge, called combination, the companies expect the participation and interaction among the PMO teams of the production, sales and quality departments.

Company 1 manufactures product prototypes to ensure that employees can improve the ideas. Company 2 seeks suggestions from different departments to improve product technology.

In internationalization, which is the process of transforming explicit knowledge into tacit knowledge, the companies seek to maintain documentation of all stages of the projects.

Company 1 seeks to maintain a record of all project changes through software; certain employees are also chosen to test the functionalities of the products in their homes.

When required, Company 2 sponsors training for its clients. In this manner, the organization can learn the possible difficulties encountered by users, determining what can be improved in future projects and learning the market needs. Moreover, the company has a testing room in which its project team can evaluate the developed products in order to improve their design and technology.

Based on the SECI model, although the PMO of Company 1 does not have a consolidated structure, many similarities between the development activities of companies are observed.

When a PMO is at a structuring stage, such as in Company 1, there are activities and routines in place for ensuring the team involvement and the understanding that those activities must be part of their daily tasks. Once the PMO is structured, such as in Company 2, the team involved no longer develops methods to maintain and share knowledge, as confirmed by the subject whom we interviewed.

The manager who was interviewed in Company 2 understands and raises the awareness of his team regarding the relevance of sharing and knowledge management before, during and after projects. According to this manager, this process depends on the organizational culture and on the relationship amongst the PMO team.

Company 1, in contrast to Company 2, is not fully aware of the importance of knowledge management for the PMO. The manager interviewed confirmed that knowledge management is time consuming and that capturing tacit knowledge from employees is complicated. “Sometimes I'm thinking about new methods that help in the full knowledge sharing, as I analyze whether the team members share all the knowledge or just part of it, i.e. the only ones to share knowledge are those who want to move to the other at that time”. Company 1 -Manager.

Müller et al. (2013) suggest that new knowledge, to be developed within the PMO, would require exchanges between PMO members, which appear to occur more in formal meetings rather than ad hoc in day-to-day work.

In addition, the manager from Company 1 reports that the organization does not have the culture necessary to store knowledge because it is a family-owned company, with top management composed of heirs who will always pass on their knowledge.

For Company 2, the benefits of knowledge management by the PMO are apparent. Amongst the benefits is the improvement of the decision-making process as a result of the greater involvement of the team. The answers to the problems that arise during project execution materialize faster, thus reducing rework and improving productivity. Consequently, the relationships among employees improve and increase the teamwork affiance.

For Company 1, knowledge management is important for the memory of organization, for verifying its evolution in project development, in realizing increased team involvement, and seeking common objectives.

It is difficult for companies to demand from its employees the sharing of their tacit knowledge in order to support project development. Sharing explicit knowledge within the group is also difficult; however, there is a need for maintaining this knowledge within the company.

The growing complexity of project work means that an increasing number of technical and social relationships/interfaces must be considered by project managers for adapting knowledge and experiences from daily work and from earlier projects. Project team members frequently need to learn things already known in other contexts; in effect, they must acquire and assimilate knowledge that resides in the organizational memory (Ajmal et Koskinen, 2008).

Figure 4. Cross-case analysis – the SECI model application

5 Conclusions

This paper aims to investigate the converting tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge in PMOs. The case studies have shown that the SECI model can help to bridging the mechanisms of projects knowledge to the mechanisms knowledge of the firm through PMO. Moreover, the key organizational factors were addressed.

This study enables to identify how PMOs performed the stages of knowledge management - socialization, externalization, combination and internalization; transforming tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge. For implementing the SECI model in the PMO level, the employees of the studied companies understood the factors that can influence the process of KM, in addition to the importance of the communication and the storage in all KM phases during the project lifecycle.

The organizational factor that influences these knowledge stages in PMOs standing out in both cases was the organizational culture. Primarily, it can impact because PMO coordinators and project managers apply methods and techniques, but ad hoc and not frequently. The importance of an effective KM is still not recognized in both companies, which impacts in the employees’ behavior in following KM processes designed by the PMO. There is a lack of commitment for turning available project reports, sharing information and disseminating all the knowledge created by the project in the organizational level, despite risking knowledge loss. The organizational culture can largely determine how the members of an organization interact with one another, for example, an organizational culture that is open and that encourages discussion will promote communication and knowledge sharing, whereas an organizational culture that nurtures mistrust and power struggles will inhibit the free exchange and knowledge sharing, which is considered a source of power among members of such an organizations (Watanabe et al., 2011). It is possible to conclude that organizational actions need to be taken regarding managerial implications, by identifying the main organizational factor influencing knowledge dissemination in PMOs.

By analyzing the PMOs in both cases, from one side, it is confirmed that PMO centralizes the collection and storage of the project knowledge, the lessons learned, and the models, and the methods and tools employed. The records of project performance, such as status reports, variable analyses, changes in initial plans, risk lists, and other information regarding successful or unsuccessful previous projects, can be stored in a database of lessons learned, which can be referred to in future projects, in accordance with (Elonen et Artto, 2003; Dai et Wells, 2004; Aubry et al., 2011; Rose, 2010; Unger et al., 2012).

On the other side, this study contributes to the understanding in terms of how difficult it is for PMO to make employees to share their tacit knowledge in order to support project development. A lack of appropriate tools for putting it in practice is also observed. The SECI model assisted in visualizing the process of transforming tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge and in the understanding that knowledge must be incorporated into operational practices, rules in databases, and company history. In this manner, increasing the awareness of employees is the first step for initiating the process.

Furthermore, the benefits of applying the SECI model in the PMO are not just related to the sharing and storage of all the knowledge because they can be useful to other members, but also to put in practice the knowledge creation spiral. PMO is critical for maintaining the memory of projects and making it accessible within the company, for the development of present and future projects, helping the communication process between PMO employees also between PMO and others departments. This perspective was common for both case studies.

Another critical role is to catalyze knowledge creation spiral, nurturing all stages of this spiral. Just one of the cases studied explores knowledge management in depth, in which case one of the primary functions of the PMO is to help creating, managing and disseminating acquired knowledge in projects.

The contribution of this to project managers is the emphasis on the importance of the management of knowledge, knowledge sharing and storage of knowledge during the development of projects. Mainly the PMO has an important role in terms of the storage and sharing of knowledge process. It contributes to the theory by presenting the steps of the knowledge spiral, using the SECI model for the conversion of knowledge, the stage and how companies apply this conversion, showing that these processes happen daily and continuously if the team understands this need.

This paper may stimulate further research focused on the aspects related to the organizational culture as a motivating factor rather than knowledge management in PMOs and research focused on the effectiveness of knowledge management within PMOs; thus, future research could seek to analyze whether the information that is stored can truly be applied in future projects. Moreover, future research could seek to explore the knowledge creation spiral in a project lifecycle and align it to PMO activities; to consider tools and techniques is also a derivate theme.

One of the limitations of this research, which must be acknowledged, is due to the methodological choices, such as the specificities of the studied organizational context such as company size and sector, not allowing generalization and it can significantly impact the organizational factors explored in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the reviewers for their relevant contributions. This research was supported by the National Counsel of Technological and Scientific Development (CNPq) and Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES). We greatly thank them for supporting this research.

References

Ajmal, M. et Koskinen, K. U. (2008). Knowledge Transfer in Project-Based Organizations: An Organisational Culture Perspective, Project Management Journal, Vol. 39, pp. 7-15.

Alavi, M. et Leidner, D.E. (2001). Knowledge management and knowledge management systems: conceptual foundations and research issues. Management Information Systems Research Center, Vol. 25.

Alin, P., Taylor, J. E., Smeds, R. (2011). Knowledge transformation in project networks: A speech act level cross-boundary analysis. Project Management Journal, Vol. 42, pp. 58-75.

Alkhuraiji, A, Liu, S., Oderanti, F.O., Megicks, P. New structure knowledge network for strategic decision-making in IT innovative and implementable projects. Journal of Business Research, Vol. 69, pp. 1534-1538.

Andersson, A. et Linderoth, H.C.J. (2008). Learn not to learn – A way of keeping budgets and deadlines in ERP-projects? Enterprise Information Systems, Vol. 2, pp. 77-95.

Aubry, M. et Hobbs, B. (2011). A Fresh Look at the Contribution of Project Management to Organizational Performance. Project Management Journal, Vol. 42, pp. 3-16.

Aubry, M. et Müller, R.; Glückler, J. (2008). A new framework for understanding organisational project management through the PMO. International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 25, pp. 38-43.

Aubry, M. et Müller, R.; Glückler, J. (2011). Exploring PMOs through community of practice theory. Project Management Journal, Vol. 42, pp. 42-56.

Bock, M. T. (1999). Baxter Magolda's Epistemological Reflection Model. New Directions for Student Services.

Bower, D.C. et Walker, D.T. (2007). Planning knowledge for phased rollout projects. Project Management Journal, Vol. 38, pp. 45–60.

Carvalho, M.M. et Rabechini Jr. R. (2011). Fundamentos em gestão de projetos. São Paulo: Atlas, 2011.

Dai, C. et Wells, W. (2004). An exploration of project management office features and their relationship to project performance. International Journal of Information Management, Vol. 22, pp. 523-532.

Davenport, T.H. et Prusak, L. (2000). Working knowledge: How organizations manage what they know. ACM IT Magazine and Forum.

Davenport, T.H., Long, D.W., Beers, M.C. (1998). Successful knowledge management projects. Sloan Management Review.

Davis, K. (2014). Different stakeholder groups and their perceptions of project success. International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 32, pp. 189-201.

De Long, D. W. et Fahey, L. (2000). Diagnosing cultural barriers to knowledge management. Academy of Management Executive, Vol. 14, pp. 113-127.

Denford, J.S. et Chan, Y.E. (2011). Knowledge strategy typologies: defining dimensions and relationships. Knowledge Management Research & Pratice, Vol. 9, pp. 102-119.

Desouza, K.C. et Evaristo, J.R. (2006). Project Management offices: a case of knowledge-based archetypes. International Journal of Information Management, Vol. 26, pp. 414-423.

Elonen, S. et Artto, K.A. (2003). Problems in managing internal development projects in multi-project environments. International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 21, pp. 395-402.

Fong, P. et Kwok, C. (2009). Organisational Culture and Knowledge Management Success at Project and Organisational Levels in Contracting Firms. J. Constr. Eng. Manage., Vol. 135, pp. 1348–1356.

Gasik, S. (2011). A model of project knowledge management. Project Management Journal, Vol. 42, pp. 23-44.

Gladden, R. (2009). Organizational learning: How companies and institutions manage and apply knowledge. Project Management Journal, Vol. 40, pp. 106.

Gummer, B. (2000). Managing knowledge and knowledge workers in organizations. Administration in Social Work, Vol. 24, No. 4, pp. 75-92.

Gupta, A.K et Govindarajan, V. (2000). Knowledge Management's Social Dimension: Lessons From Nucor Steel. MIT Sloan Management Review.

Hallows, J. E. (2002). The project management office toolkit. New York: AMACOM.

Hobbs, B. et Aubry, M. (2010) The project management office or PMO: A quest for understanding. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

Hobbs, B.; Aubry, M., Thuillier, D. (2008). The project management office as an organizational innovation, International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 26, pp. 547-555.

Hornstein, H. A. (2015). The integration of project management and organizational change management is now a necessity. International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 33, No. 2, pp. 291-298.

Hurt, M. et Thomas, J. L. (2009). Building Value Through Sustainable Project Management Offices. Project Management Journal, Vol, 40, pp. 55-72.

Ibert, O. (2004). Projects and firms as discordant complements: organisational learning in Munich software ecology. Research Policy, Vol. 33, pp. 1529-1546.

Issa, R.R.A et Haddad J., (2008) "Perceptions of the impacts of organizational culture and information technology on knowledge sharing in construction", Construction Innovation, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp.182-201.

Johansson, C., Hicks, B., Larsson, A. C. et al. (2011). Knowledge maturity as a means to support decision making during product-service systems development projects in the aerospace sector. Project Management Journal, Vol. 42, pp. 32-50.

Kerzner, H. (2001). Project management: a systems approach to planning, scheduling, and controlling. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Knapp, E. et Yu, D. (1999). How culture helps or hinders the flow of knowledge. Knowledge Management Review, Vol. 2.

Koskinen, K. (2004). Knowledge Management to improve project communication and implementation. Project Management Journal, Vol. 35, pp. 13-19.

Koskinen, K.U. (2012). Organizational Learning in Project-Based Companies: A Process Thinking Approach. Project Management Journal, Vol. 43, pp. 40–49.

Liu, L. et Yetton, P. (2007) The contingent effects on project performance of conducting project reviews and deploying project management offices. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, Vol. 54, pp. 789-799.

Marra, M.; Ho, W., Edwards, J.S. (2012) Supply chain knowledge management: A literature review. Expert Systems with Applications, Vol. 39, pp. 6103-6110.

Martin, B. (2000) Knowledge based organizations: emerging trends in local government in Australia. Journal of Knowledge Management Practice, Vol. 2.

Martins, A.P., Martins, M.R., Pereira, M.M.M. et al. (2005) Implantação e consolidação de escritório de gerenciamento de projetos: um estudo de caso. Produção, Vol. 15, pp. 404-415.

Müller, R., Glückler, J., Aubry, M. et al. (2013) Project Management Knowledge Flows in Networks of Project Managers and Project Management Offices: A Case Study in the Pharmaceutical Industry. Project Management Journal, Vol. 44, pp. 4–19.

Nonaka, I. (1991). The knowledge-creating company. Harvard Business Review, Vol. 69, No. 6, pp. 96-104.

Nonaka, I. (1994) A dynamic theory of organisational knowledge creation. Organization Science, Vol. 5.

Nonaka, I. et Takeuchi, H. (1997) Criação do conhecimento na empresa. Rio de Janeiro: Campus.

Nonaka, I. et Toyama, R. (2003) The knowledge-creating theory revisited: knowledge creation as a synthesizing process. Knowledge Management Research & Pratice, Vol. 1, pp. 2-10.

Nonaka, I., Toyama, R., Konno, N. (2000) SECI, Ba and Leadership: a unified model of dynamic knowledge creation. Long Range Planning, Oxford, Vol. 33, pp. 5-34.

Nowacki, R. et Bachnik, K. (2016). Innovations within knowledge management. Journal of Business Research, Vol. 69, pp. 1577-1581.

Patah, L.A. et Carvalho, M.M. (2009) Alinhamento entre estrutura organizacional de projetos e estratégia de manufatura: uma análise comparativa de múltiplos casos. Gestão e Produção, Vol. 16, pp. 301-312.

Pemsel, S. et Wiewiora, A. (2013) Project Management office a knowledge broker in Project- based organisations. International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 31, pp. 31-42.

Petter, S. et Randolph, A.B. (2009) Developing soft skills to manage user expectations in it projects: knowledge reuse among it project managers. Project Management Journal, Vol. 40, pp. 45-59.

Rai, R.K. (2011) Knowledge management and organizational culture: a theoretical integrative framework, Vol. 15, pp. 779-801.

Randeree, E. (2006) Knowledge management: securing the future. Journal of knowledge management, Vol. 10, pp. 145-156.

Rastogi, P.N. (2000) Knowledge management and intellectual capital — the new virtuous reality of competitiveness. Hum Syst Manage, Vol. 19.

Reich, B.H., Gemino A., Sauer, C. (2008) Modelling the knowledge perspective of IT projects. Project Management Journal, Vol. 39.

Resende Junior, P.C. et Reis, A.L.N. (2016). Incursion of knowledge management in management excellence awards: an analysis in the latin-american context, Vol. 13, pp. 150-158.

Ribere, V.M. et Sitar, A.S. (2003) Critical role of leadership in nurturing a knowledge supporting culture. Knowledge Management Research and Practice, Vol. 1, pp. 39-48.

Rose, K.H. (2010) The Project Management Office (PMO): A quest for understanding. Project Management Journal, Vol. 42.

Shand, D. (1998). Harnessing knowledge management technologies in R&D. Knowledge Management Review, Vol. 3, pp. 20–26. Sudhakar, G.P. (2015) A review of conflict management techniques in projects. Brazilian Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 12, pp. 214-232.

Tukel, O.I., Kremic, T., Rom, W.O. et al. (2010) Knowledge-salvage practices for dormant R&D projects. Project Management Journal, Vol. 42, pp. 59–72.

Unger, N.U., Gemunden, H.G., Aubry, M. (2012) The three roles of project portfolio management office: their impact on portfolio management execution and success. International Journal of Project Management.

Voss, N.T. et Frohlich, M. (2002) Case research in operations management. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 22, pp. 195-219.

Watanabe, R.M., Benton, C., Senoo, D. (2011) A study of knowledge management enablers across countries. Knowledge Management Research & Pratice, Vol. 9, pp. 17-28.

Yin, R.K. (2003) Case study research: design and methods. Sao Paulo: Sage Publications.